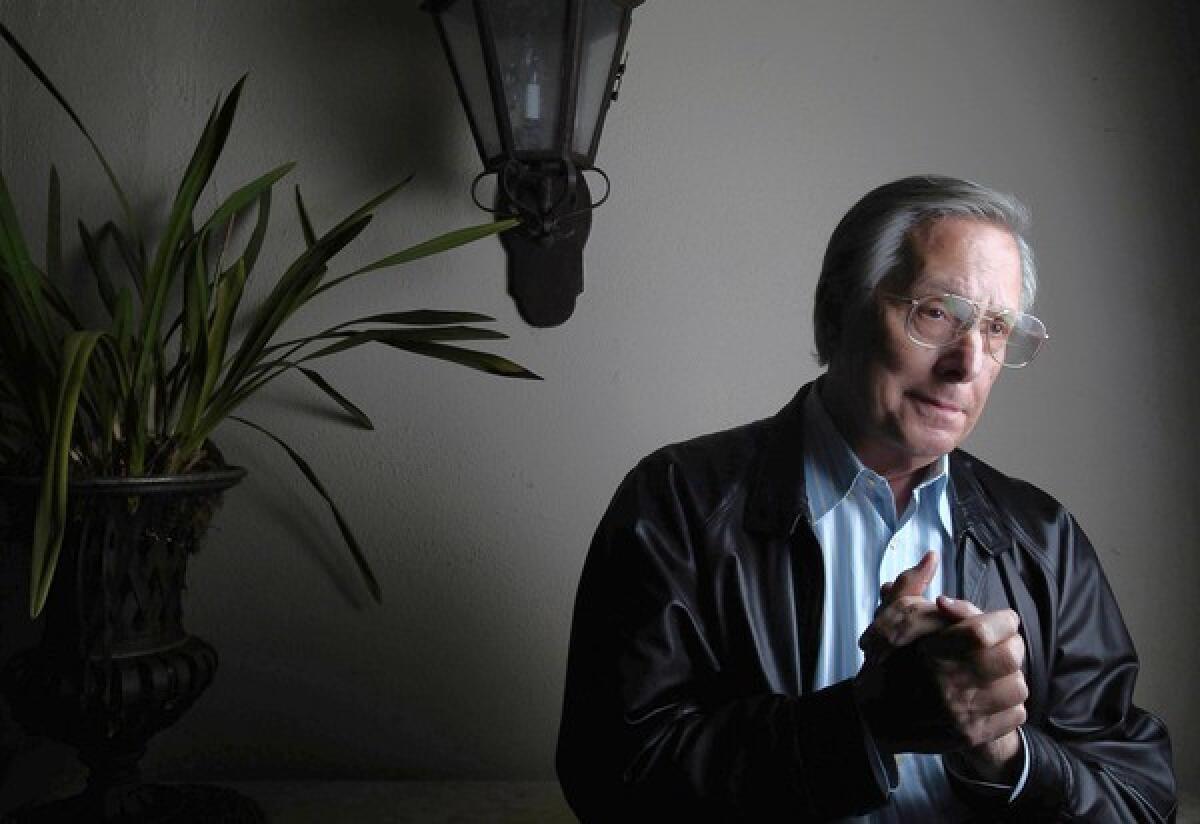

William Friedkin takes a high-speech chase through his career

Filmmaker William Friedkin, who’s best known for such landmark films as “The French Connection” and “The Exorcist” in the early ‘70s, looks back on a long career directing movies, opera and theater in his new memoir, “The Friedkin Connection.”

Why do you think Sonny Bono, whom you directed in the 1967 film “Good Times,” was a genius, as you write?

Sonny Bono was a guy who created a number of No. 1 hit songs in the ‘60s. At first they might have sounded to a lot of older people like popcorn songs, bubble gum, but those songs, many of them, are really strong and they stand the test of time. He would go into a recording studio — it was called Gold Star Studios, they were on Santa Monica — it’s the place where Phil Spector had created the wall of sound, and Sonny was a gofer for Phil Spector. He picked up his knowledge of producing from Spector. He would go into a studio, hire a band of 12 to 20 pieces. There would be no written music. He’d hum or tell them what to play. After he spent three or four days creating — I would have to say painting sound — he would then sit down with a piece of paper or a bag that carried someone’s lunch, and he’d write a lyric. Now it’s not Stravinsky, but Stravinsky never sold 100 million records either.

You also write that your conversations with the playwright Harold Pinter were “the most valuable and instructive of my career.” What did you learn from him?

A sense of drama. How to take what appeared to be a simple moment — sometimes an almost irrelevant moment — and just pack it with meaning and feeling and an ambiguous sense of something going on beneath the surface, and more than anything else, a kind of suspense. He changed playwriting in the English language. Pinter was every bit as important to modern British and English-language playwriting as Shakespeare was in his day. I’m going to do a production of “The Birthday Party” in January at the Geffen.

How did the upcoming revival of “The Birthday Party” come about?

Randall Arney, who’s the [artistic] director at the Geffen, asked me if I would be interested in doing some Pinter for them, because he knew I’d directed the film of “The Birthday Party” 50 years ago. I like the Geffen. My feeling has always been that if I like the material and someone asked me to do a play, if it’s in a church basement, I’ll do it.

Let’s talk about “The French Connection.” You didn’t want Gene Hackman in the lead role of Popeye Doyle?

No. I just didn’t see him in the part at the time. Now I can’t see anyone else, obviously. But my original choice was Jackie Gleason. A black Irishman is more of a brooding figure, and that’s how I saw Eddie Egan [the detective who inspired the film], who is Popeye Doyle in the movie. And I saw him physically as Jackie Gleason — a heavyset black Irishman.

Why wasn’t he cast?

Dick Zanuck was the head of the studio who greenlit “The French Connection.” He said there was no way that was going to happen. He said Gleason had made a film for Fox called “Gigot,” which was a silent movie about a clown. And as Zanuck described it, it was the biggest disaster in the history of Fox. So they didn’t want to do another movie with Gleason.

We actually offered the part to Peter Boyle, and he turned it down. He wanted to do romantic comedies. He looked in the mirror, I guess, and saw Cary Grant. And Mel Brooks saw Young Frankenstein.

I was interested to read about your 90-mile-per-hour chase scene down real New York City streets with real people. How did that escape the attention of real police?

It was on Stillwell Avenue in Brooklyn, which was very near Coney Island. And there was not heavy police patrol then. But it wouldn’t have mattered if there was because I had with me, almost at all times, the two actual “French Connection cops” and their colleague. And in the car with me was a detective named Randy Jurgensen, who had his badge. We didn’t tell anyone we were going to do this, but if we had gotten stopped, Randy would show his badge and talk them down. We had finished the shot before anyone caught on.

But there was a time in that film when we were shooting on the Brooklyn Bridge, and I wanted a traffic jam. So I sent these detectives down to park their cars on the Brooklyn Bridge, and we created a traffic jam and, in that case, a police helicopter landed down near where we were. And the officers came up on the bridge, and said, “What the hell are you guys doing?” And Sonny Grosso and Randy Jurgensen and Eddie Egan, who were the French Connection cops, they showed their badges and said, “We’re just making a movie and we’ll be out of here in a couple of minutes.” We were.

In those days, I just shot everywhere without permits — except on the elevated train. If we didn’t get permission to do it — and we had to pay a guy off — I was just going to steal it anyway. Just get on the trains and do it with real people, wondering what the hell was going on.

Ah, youth.

Exactly. I would not do that today. And I advise nobody to try it at home.

How would “The Exorcist” be different if you made it today?

It would be a lot easier to do in terms of computer-generated imagery, rather than have to do all that stuff mechanically as we did. But it would have been more expensive.

Would you add effects that you wouldn’t have been able to create mechanically?

I don’t know that I would have added anything. I wasn’t about to invent some demonic manifestations. The diaries in that case were plenty graphic enough.

Did your research for “The Exorcist” convince you of the reality of demonic possession?

In that case, yes. There are only three cases in the 20th century that the Catholic Church in the United States has authenticated as cases of demonic possession warranting an exorcism, and that was one of them. I was shown the diaries of the doctors, nurses, priests and some of the patients at Alexian Brothers Hospital in St. Louis, where the exorcism was performed. I have no doubt that those accounts are what happened. Now what they mean and whether or not in the future somebody might find a medical or a psychiatric cure for those symptoms, I don’t know.

You also write about your fear of dying before you’ve accomplished enough. Do you think you’ve met that mark yet?

No. When I was dying of a heart attack on the Warner Bros. lot in the infirmary [in 1981], I heard one paramedic say when he was using a defibrillator, “I’m not getting anything.” And I remember thinking, Oh my God, I’m dying and I’ve accomplished nothing in my life. And I faded out. And I remember hearing a voice, as I recall it was a woman’s voice, and it said, “It’s OK, it doesn’t matter.” It was a very soft gentle woman’s voice, and I was moving through darkness as though on an escalator toward a light.

By the way, the other day I opened the L.A. Times to the obituary page, and there’s my picture. It turns out they were describing the death of the special effects man on “The Exorcist,” Marcel Vercoutere.

What’s on your horizon other than “The Birthday Party”?

I’m working on three different screenplays at once. I’m not sure which of them I’ll have ready, but I hope to do another film this year. But when I finish my book tour, I have to come back and record the audio book. Then I’m going to make a new digital version of my [1977] film, “Sorcerer,” which is coming out again this year in theaters and on home video. Then “Sorcerer” will be world premiered at the Venice Film Festival on my birthday, Aug. 29. Then on Oct. 30, “The Exorcist” is going to have its new theatrical world premiere at the Smithsonian.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.