Simon Schama’s ‘Story of the Jews’ sets stage for an even darker tale

Whatever you might say about Simon Schama, one of our most prominent and accomplished narrative historians, you can’t say he’s afraid to tackle broad and challenging subjects. “The Story of the Jews” is the first of a two-volume work aimed at covering 3 millenniums, from 1000 BCE to the present day, with the break coming at 1492 and the expulsion of the Jews from Spain by Ferdinand and Isabella.

That’s a lot of ground to cover, greater geographically if not in chronological terms than Schama’s last multi-volume work, a three-tome “History of Britain” published in 2000-02 that reached all the way back to 3500 BC. Like that work, the scale of “The Story of the Jews” was dictated by the requirement of a television documentary series, scheduled to begin airing on PBS toward the end of this month. Schama might want to select his inspirations more judiciously in future, for the subject at hand comes close to overmatching even his prodigious talents.

The main signs of struggle come at the beginning of the story, set in the deep pre-biblical past. The difficulty — often, the impossibility — of separating fact from myth, legend and archaeological speculation sometimes reduces Schama’s narrative to a muddle. One gets lost tracing the peregrinations of the early Jews between Babylon and Egypt, between the Euphrates and the Nile, or distinguishing between the Jewish communities of Judea (roughly present-day Israel), and Elephantine, an island in the Nile, as distinctive as they were.

Schama resorts to two techniques to work around the muddle. One is to focus on the defining characteristic of the Jewish people, which is their devotion to the book — or more precisely, the words. As he perceives, it can be enormously effective to track the development of the Jews as a community by watching the development of what would coalesce into the Torah.

“The genius of the Israelite-Judahite priestly and scribal class...,” Schama observes, “was to sacralise movable writing, in standardised alphabetic Hebrew, as the exclusive carrier of YHWH’s [that is, God’s] law and historic vision for his people. Thus encoded and set down, the spoken (and memorised) scroll could and would outlive the monuments and military force of empires.” This is a theme that runs through the entire book, and one could not hope for a more effective unifying image.

Rather less helpfully, Schama attempts to finesse the uncertainties of the historic record by reporting on the present-day archaeological investigations that strive to fill in its blank spots or perhaps reinterpret the discoveries of earlier generations of archaeologists.

This is a fascinating story, yet it feels misplaced in this volume, especially because the conclusion one draws from Schama’s extended description of the excavations at Khirbet Qeyafah, an ancient fortress a few miles west of Jerusalem, is that the history of the Jews of its time (about 1000 BCE or earlier) is still being prised from beneath the dust deposited by the succeeding millenniums.

Schama is on firmer ground as he moves forward to the Christian era. Here a dark story grows darker, shadowed by a conflict that began, Schama writes, as a “family quarrel. That, of course, did not prevent it from going lethal, early; perhaps it guaranteed it.” Like most historians of the era, Schama finds the roots of Christian anti-Semitism in the eight infamous homilies of John Chrysostom.

From his pulpit at Antioch in the late 380s, Chrysostom showered abuse upon the Jews of his community, his purpose being to end the social intermixing of Jews and Christians with their incompatible world views. “It was, for the first time, a true social pathology of the Jews,” Schama writes of the homilies.

Their demonization was thorough and uncompromising: “The Jews as conspiratorial ravening kidnappers, required by sacred rites to devour Gentiles they had fattened for the purpose,” killers of Christ, “no better than pigs,” cheats, plunderers, only “fit for killing.” Chrysostom’s legacy, in word, image and act, has been lasting. But it began, as Schama tells, with this shattering of the idea that an urban world could be shared between Jews and Christians.

The word, the book, weaves its spell through these pages too, from the Mishnah, the commentary on the Torah that sprung from the tradition of the Oral Law and became codified in the second century, and its elaboration, the Talmud. Sages walk these chapters — Rabbi Judah of the Mishnah, and Maimonides, the great interpreter of that great interpretation, the Talmud.

The books were central to Jewish life, and therefore their destruction central to the destruction of the Jewish community, never more so in the period covered by this volume than the burning of the Talmuds of Paris, convicted of blasphemy, during a day and a night in June 1242. Twenty-four carloads of books written on parchment and bound in vellum were put to the torch, an assault that in Schama’s hands preserves its capacity to shock, eight centuries later. “The bigger books were so densely packed with leaves that at night they took on an amber glow, thickening the Paris air with a sweetish animal stink.”

The grief of the Jewish community was unbounded: “To set fire to a book was as if a living body had been burned on the pyre.”

From there the eviction of the Jews from their European homes proceeded, gathering force. Ferdinand of Aragon married Isabella of Castile in 1474 and proceeded with the “great erasure of Jewish life in Spain” — separated from Christian community by command and then cursed for their apartness. Torquemada elevated the spectacle of public punishment to “mass entertainment,” the auto-da-fé. To characterize of the Inquisition as directed at “heretics” is to bandy a euphemism: the targets overwhelmingly were those “who once had been and were suspected of still being Jews.”

The year 1492, celebrated in the New World as the dawn of discovery, casts a baleful shadow over Jewish history. It comes at the end of this uneven, sprawling, often stirring and fascinating volume, and sets the stage for a Volume Two that will encompass an even darker story.

Hiltzik, a Times business columnist, is the author of “The New Deal: A Modern History” and “Colossus: The Turbulent, Thrilling Saga of the Building of Hoover Dam.”

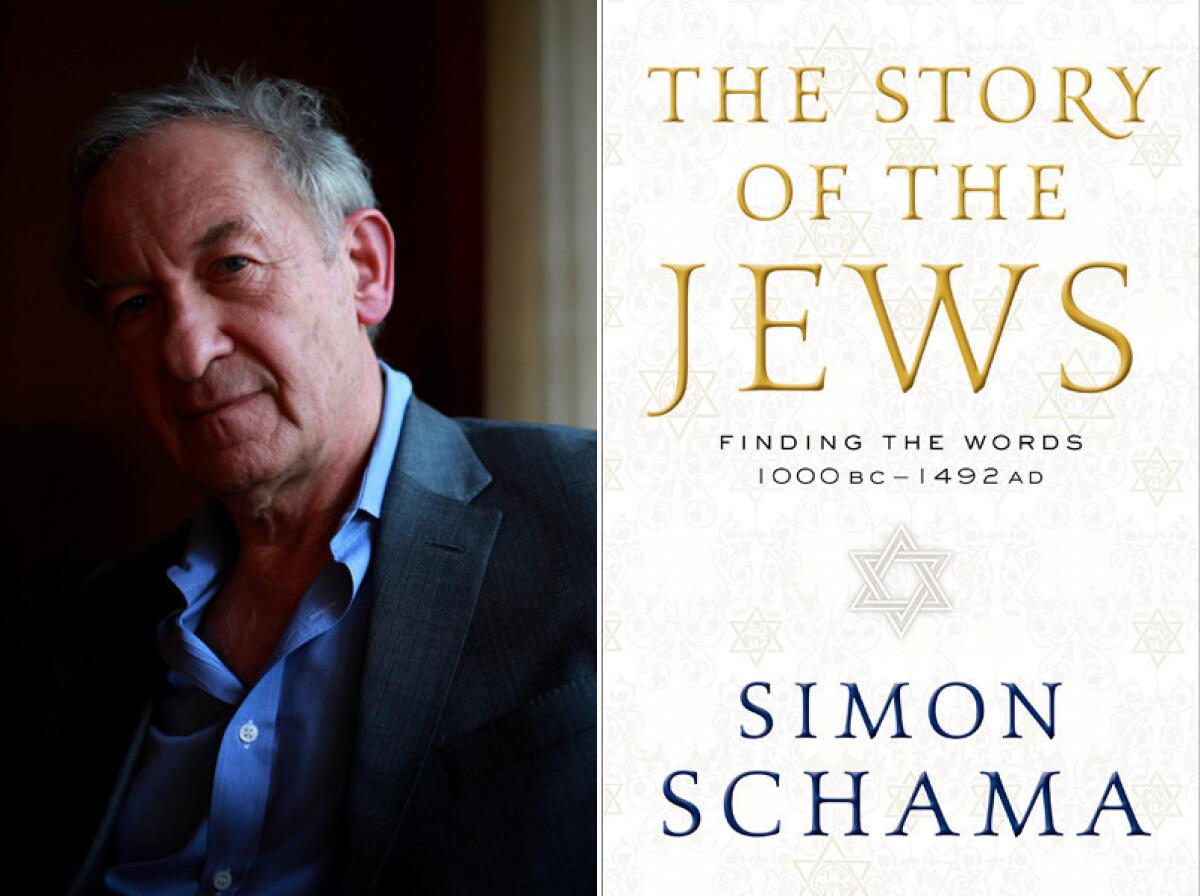

The Story of the Jews

Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD

Simon Schama

Ecco: 512 pp., $39.99

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.