‘Sex and Rage’ have always been the territory of the It Girl

People love an artist’s muse. The glamour of the position is naturally implied. She has to be beautiful for the artist to become obsessed. She has to be at the right parties in orderfor to be discovered. If the status also generally comes with some kind of debilitating addiction — as it did for, say, Edie Sedgwick — well, even that is sort of glamorous. Everybody, in theory, wants to be an It Girl, no matter the cost.

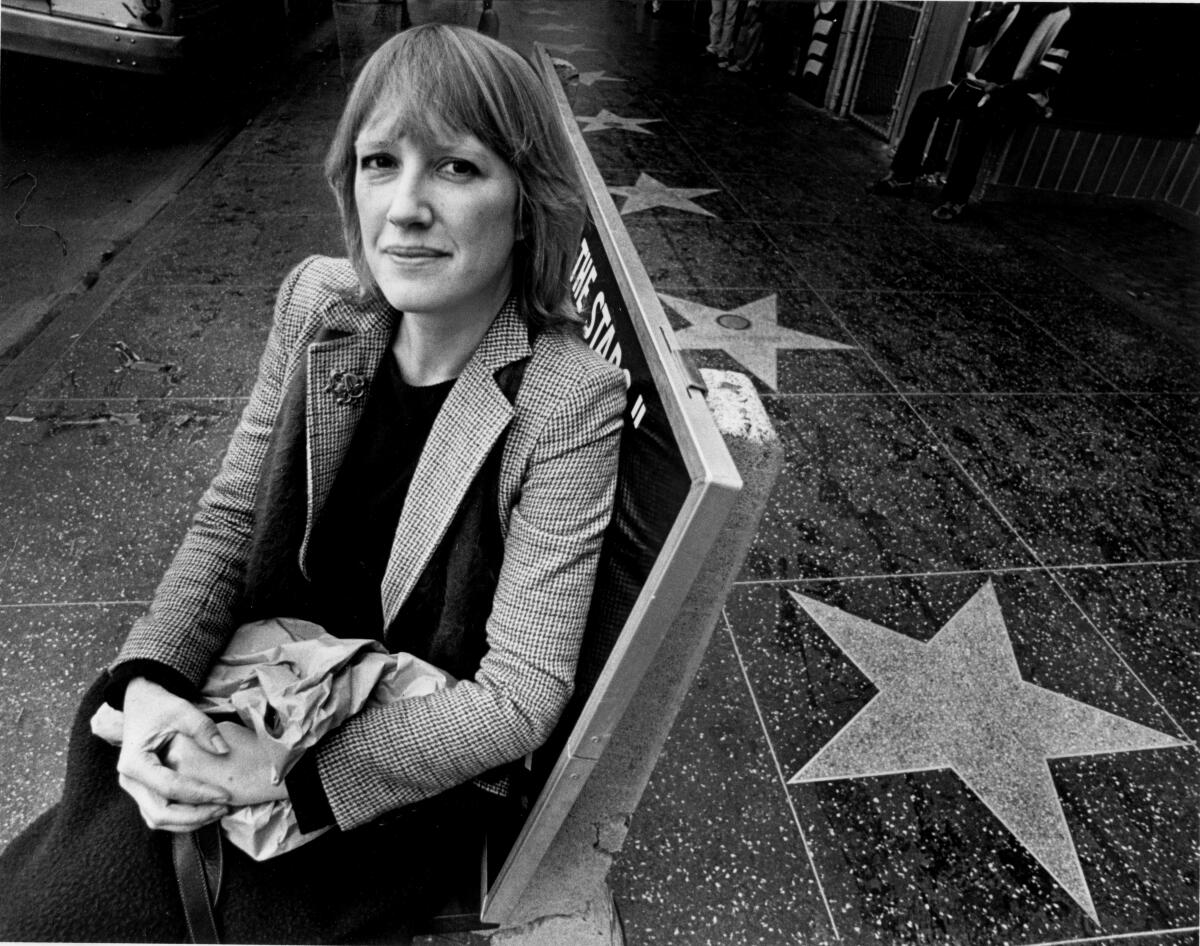

Eve Babitz, a writer of the 1970s and 1980s who has been recently rediscovered and reprinted by prestigious literary presses, was very much an It Girl. She was born and raised in Los Angeles, just in time for its seedy-but-cool era of the 1960s and 1970s, when the Golden Age of Film crossed over into the Golden Age of LSD. As a 14-year-old, she found herself in the car of a man who turned out to be Johnny Stompanato. She hung out at the famously debauched Garden of Allah hotel on Sunset. She dated musicians and artists and, yes, Harrison Ford. (Did everyone date Harrison Ford? It’s beginning to feel like it.)

Babitz had her photograph taken with Marcel Duchamp. In the photograph, she is naked, and he is not, and they are playing chess. It’s all very self-consciously iconic, so much so that in “Sex and Rage,” a novel Babitz first published in 1979 that has now been reissued by Counterpoint Press, the main character, Jacaranda Leven, sees the photograph and thinks to herself that she would have to be an idiot “to spend all her time around artists and not see this photograph.”

Everybody, in theory, wants to be an It Girl, no matter the cost.

It’s a moment of explicit self-mythology that sounds unbearably egotistical, and yet, in context, it mostly works, because Babitz (now 74 and retired from public view) is a very charming writer and egotism can actually go over pretty well, if you’re winning about it. Babitz’s essays — in her recently reissued “Eve’s Hollywood” and “Slow Days, Fast Company” — are all exercises in charm, gossipy without quite tipping over into pure name-dropping.

“Sex and Rage” is less controlled, and in my view, a more interesting work from Babitz. Jacaranda shares some of her biographical markers but not all of them, giving her room to experiment. And though the book is plotless, told in vignettes, and this will bedevil some readers, there is something about its portrait of an It Girl on the verge of a nervous breakdown that softens and opens the type. “People told Jacaranda she was lucky,” Babitz remarks early on, but luck is not enough. “Jacaranda wanted to see things before her luck ran out and she came upon the prophesied brick wall.”

Jacaranda rarely seems very glamorous to us. Despite the title, there’s not much actual rage on view here, either. She starts out as a wayward teenage surfer with calcium deposits on her knees. It takes falling in love with someone to make her beautiful. And she is not, exactly, your typical party girl. “For the first six months” that Jacaranda occupies a particular apartment in Santa Monica, Babitz tells us, “all she wanted was honest labor, finely crafted novels, and surf.”

These hints at Jacaranda’s ordinariness are, of course, interrupted by long swaths of the expected kinds of debauchery. We watch, for example, as Jacaranda develops an alcohol problem. We watch as she collects bad boyfriend types, and also a gay or possibly asexual man named Max, with whom she becomes obsessed. At some point, she will party with a beautiful groupie named Sunrise. Sunrise, we are told, is “not like other people — all mortal and nose-blowy.”

Babitz (now 74 and retired from public view) is a very charming writer and egotism can actually go over pretty well, if you’re winning about it.

But through it all, Jacaranda will manage to write enough small bits of prose to cobble together a book, a novel good enough to get her a publisher in New York, which in this late 1970s cosmology is the indication that Jacaranda has Arrived. But instead of embracing her fame and success, Jacaranda avoids it. She turns in a novel draft late. She ignores her agent’s repeated entreaties that she come to New York. She tells someone that the reason she is avoiding New York is that Max is there. But to the reader she admits a secondary reason: “Jacaranda was afraid of New York… she was terrified of going someplace and being drunk all the time.”

This is an intriguing sort of fear, one so strong that Jacaranda seems hesitant to even articulate to herself. There is usually very little space for hesitation in stories like hers. We have a way of projecting a certain natural confidence onto It Girls. Even where, say in the work of Joan Didion, we find them bored and aimless, lost and unhappy, they are still somehow devoted to the glamour of their position. They can be as doctrinaire about their coolness as any preacher in front of his congregation.

All that allure, that veneer of endless cool, it can be a little intimidating. But Babitz is up to something more interesting by the time she plants Jacaranda in the legendary New York artist’s watering hole called Elaine’s. Jacaranda looks around that room with ambivalence. “In Elaine’s it was almost impossible to pull off being incredibly beautiful and splashy and fabulous,” she remarks. It fits, because most of “Sex and Rage” seems to be about the difficulty of pulling off that It Girl illusion too.

Dean is the 2017 recipient of the Nona Balakian citation for excellence in criticism awarded by the National Book Critics Circle. She is the author of the forthcoming book “Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion.”

Eve Babitz

Counterpoint: 256 pp., $16.95 paper

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.