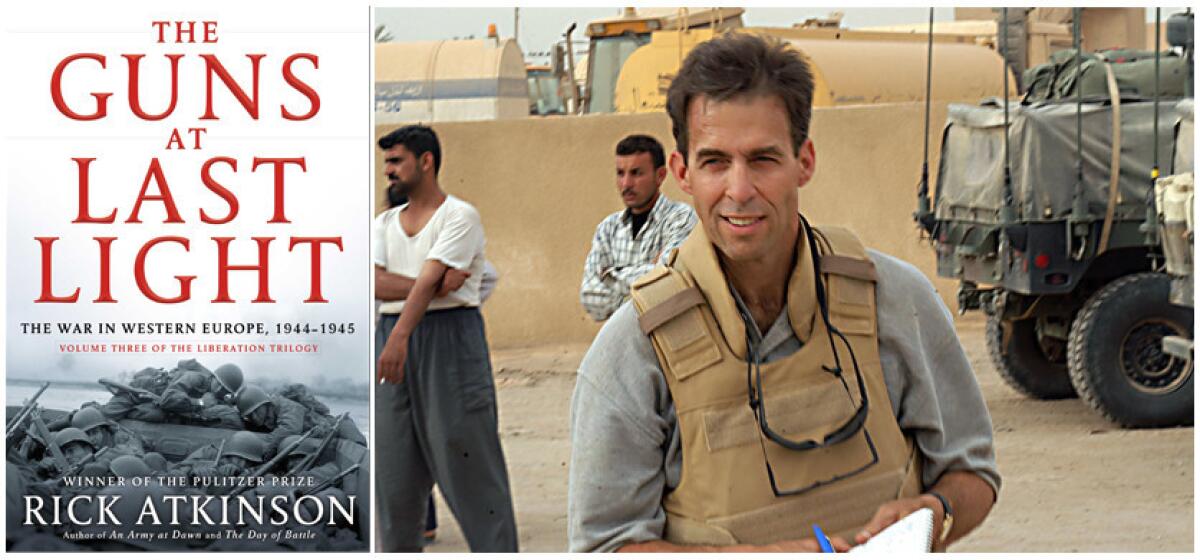

Rick Atkinson closes his war trilogy with ‘The Guns at Last Light’

After calling it a masterpiece of deep reporting and powerful storytelling, what more needs to be said of Rick Atkinson’s trilogy about World War II?

The first volume, “An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942-1943” received the Pulitzer Prize for history. The second, “The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944,” concerned a middle section of the war often overlooked by historians.

Now comes the finale, “The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945.”

The challenge of the third volume would seem to have differed from that of the first two, which dealt largely with events that, while complex and consequential, are not the continuing focus of movies and documentaries.

The story of the Allied drive from D-Day to Berlin is far better known to the public. Finding new material and presenting a fresh take on well-trod material, like the uneasy relationship between coalition partners, might have been daunting in lesser hands.

But Atkinson, a former reporter and senior editor at the Washington Post, is more than equal to the task. “The Guns at Last Light” continues and deepens themes and character studies seen in the first two volumes.

Atkinson’s admiration for the American force, from its leadership to its lowest-ranking infantry soldier, is rightfully enormous. The morality of the Allied cause is never in doubt. But he is not captive to the “good war” or “greatest generation” idolatry.

The Americans, even Dwight Eisenhower, made battlefield mistakes, costing lives. There were screw-ups, logistics problems, petty jealousies and blind spots. The harsh European winter seemed to catch the Americans by surprise, several years running, Atkinson writes.

The American generals were feuding among themselves, the British generals were feuding with the Americans, and everyone was feuding with the French leader Charles De Gaulle and his self-aggrandizing habit of referring to himself in the third person.

Eisenhower wrote to Gen. George Marshall that next to the bad weather, the French “have caused me more trouble in this war than any other single factor. They even rank above landing craft.”

But Eisenhower knew that the art of command “at times requires tactical retreat for strategic advantage, in a headquarters no less than on a battlefield, and by midday on Wednesday the supreme commander sensibly recognized that in the interest of Allied comity he would have to yield” to De Gaulle’s latest demand, Atkinson writes.

As befits a journalist who knows his material inside and out, Atkinson can provide the incisive explanation to a complex situation or personage.

Of the British general Bernard Montgomery, he writes, “Knowing and unknowing, he could offend, rankle, enrage. Hardly a fatal flaw for a subaltern brawling in the trenches, this defect proved near mortal in coalition warfare, when political nuance and national sensitivities could be as combustible as gunpowder.”

Much of the trilogy — which took Atkinson 14 years to produce — can be read on two tracks: dealing with the specific circumstances of World War II and also making a generic comment about the brutality of modern warfare.

Of civilian casualties, he writes, “All told, three thousand Normans would be killed on June 6 and 7 (1944) by bombs, naval shells, and other insults to mortality; they joined fifteen thousand French civilians already dead from months of bombardment before the invasion.”

And of a condition now called post-traumatic stress disorder, “…by mid-July (1944), such neuropsychiatric cases would account for one of every four infantry casualties in 21st Army Group, with the worst of them ‘crouched down like hunted animals’ in battalion aid stations.”

There were also more than 500 cases of “S.I.W. — self-inflicted wounds, typically a gunshot to the heel, toe or finger.”

If Atkinson dealt with only the major figures, Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley (he’s no fan), Montgomery, Rommel, Marshall, et al., the trilogy would still be monumental. But all three books are full of lesser-known battlefield leaders such as Lt. Gen. Jacob Loucks Devers, a maverick who understood tank warfare in the late 1930s while other officers were pining for the return of the cavalry.

Devers’ scratchy, egotistical personality alienated Eisenhower (“Ike hates him,” Patton wrote in his diary) but the supreme commander understood that Devers had what it takes to be the modern warrior: bravery and brains, for sure, but also the ability to navigate political shoals.

Near the end of “Last Light,” almost as a coda to his trilogy, Atkinson writes about the 60% of American fatalities whose remains, at the request of their families, were brought back to the U.S. at a cost to the government of $564.50 per body, “an unprecedented repatriation that only an affluent, victorious nation could afford.”

Henry Wright, a Missouri farmer and widower, awaited the bodies of his three sons: one killed at the Bulge, one who died in a German prison camp, one who died just two weeks before the war ended. In a quiet, understated manner, Atkinson sets the scene:

“Gray and stooped, the elder Wright watched as the caskets were carried into the rustic bedroom where each boy had been born. Neighbors kept vigil overnight, carpeting the floor with roses, and in the morning they bore the brothers to Hilltop Cemetery for burial side by side beneath an iron sky.

“Thus did the fallen return from Europe, 82,357 of them.”

The Guns at Last Light

The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945

Rick Atkinson

Henry Holt & Co.: 877 pp., $40

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.