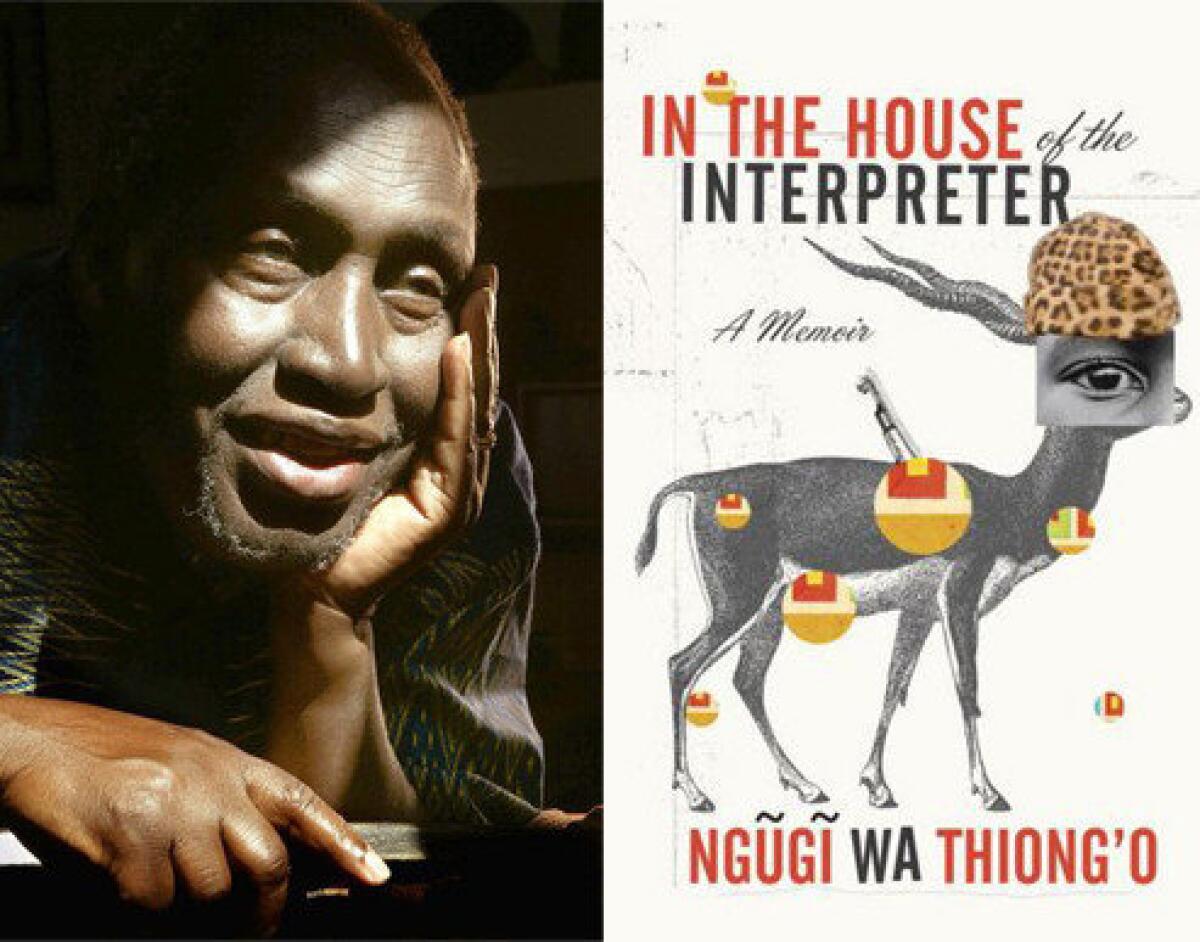

Ngugi wa Thiong’o soars ‘In the House of the Interpreter’

In the House of the Interpreter

A Memoir

Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Pantheon: 256 pp., $25.95

“In the House of the Interpreter,” the new memoir by the celebrated African writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o, takes us to the hopeful and turbulent world of 1950s Kenya. And it begins with a startling image.

Ngugi is a teenager, returning home from his prestigious boarding school. He’s finished his first term at the top of his class and is still wearing his khaki school uniform and blue tie. Carrying his belongings in a wooden box, he reaches the ridge where his village should come into view. But it’s not there.

Instead he sees his family homestead “is a rubble of burnt dry mud, splinters of wood, and grass.” All the other homesteads have been reduced to ruins too. “There is not a soul in sight.” A wandering friend reveals the village’s fate: It’s been swallowed up by the British Empire’s offensive against Kenya’s Mau Mau guerrillas.

“In the House of the Interpreter” is the second volume in Ngugi’s series of memoirs. It’s a work of understated and heartfelt prose that relates one man’s intimate view of the epic cultural and political shifts that created modern Africa.

The first installment was the elegiac “Dreams in a Time of War.” Published in 2010, “Dreams” covered Ngugi’s childhood in rural Kenya as the son of Thiong’o wa Nducu and one of his four wives. Throughout his boyhood, Ngugi is witness to a slowly changing Kenya. New railroads and highways link his village to a vast, English-speaking empire. But the forces of modernity haven’t yet changed life much for the Gikuyu people.

“Dreams in a Time of War” ends with Ngugi’s passage into manhood — after a ritual circumcision — and his acceptance into an elite school set aside for top black students in the British colony’s segregated education system.

“In the House of the Interpreter” tells the story of Ngugi’s four transformative years in that school, Alliance High.

Inside Alliance’s spic-and-span classrooms and under the tutelage of its excellent British and African teachers, young Ngugi undergoes an exhilarating intellectual awakening — just as Kenya’s simmering struggle for independence begins to heat up.

He learns to recite Shakespeare’s sonnets and Christian prayers. But he lives with a secret that’s eating away at his soul: His older brother, Good Wallace, is living somewhere in Kenya’s mountains, a soldier in the Mau Mau guerrilla movement. The country is in an official state of emergency, and Ngugi worries that he’ll be expelled from school if his secret is revealed.

When he sees a school production of “As You Like It,” it triggers a daydream about Good Wallace, with Shakespeare’s lovers in a forest and Kenya’s idealistic rebels merged into a single mental image.

“I could not help comparing the exiles in Arden to my brother…wandering in the forests of Nyandarwa and Mount Kenya,” Ngugi writes.

“In the House of the Interpreter” is a book about the creation of modern Africa from the collision of a series of powerful opposing forces — nationalism and colonialism, rural tradition and capitalist modernity. We see these changes through the eyes of a group of bright, ambitious teenagers.

Alliance High is an African Hogwarts, without the magic. All the students join happily in competitions between school houses. They know they’re at Alliance to become members of Kenya’s small African intelligentsia; for the British, this new black educated class will be a force of moderation and assimilation.

But the students, and especially Ngugi, can’t help but develop other ideas. They’re inspired by the leaders of newly independent former colonies, including India and Ghana. Kenya’s own nationalist leader, Jomo Kenyatta, has been arrested, but others continue to push for African liberation in the colonial legislature.

Against the revolution going on outside the school grounds, there is the aesthetically pleasing order of the Alliance school itself. The teachers and the curriculum offer the students the possibility of personal redemption through study and godliness.

The school’s message is summarized, for Ngugi, in a passage he reads in the novel “The Pilgrim’s Progress.” The novel’s hero reaches the “Interpreter’s House,” a place “where the dust we had brought from the outside could be swept away by the law of good behavior and watered by the gospel of Christian service.”

But when he leaves the Alliance campus, Ngugi enters a world of checkpoints and armed British soldiers. Returning home, he finds his family and his old village neighbors relocated into a concentration camp similar to the “strategic hamlets” of the Vietnam War.

From these painful personal experiences, a writer is born. East Africa — ethnically and culturally diverse, filled with natural and human beauty — will eventually feed Ngugi’s writing and populate his many novels. Tolstoy and Shakespeare stir his love of writing, but it’s his family and his mother who give him the stories he needs to write.

On one visit home, his mother takes him out to the fields, cooking potatoes for him under an ancient Mugumo tree.

“She believed it was sacred and healing,” Ngugi writes of the tree. “For some reason, she made us look at its roots… They were strong and deep, and that’s why a Mugumo never succumbed to prevailing winds and changing weather…”

“Did you know that this [tree] has been here since before the coming of the colonizer,” his mother says, “even before your great-great-great-grandparents?”

Like that tree, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Kenya endures. And it comes alive in the pages of his brilliant and essential memoir.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.