Javier Marías’ elegant novel ‘Thus Bad Begins’ is filled with secrets

Novels are about secrets, inherently so, as the author knows just how a story ends, what happens, who did what and where the bodies are buried. A reader, on the other hand, knows nothing really at all, save what happens in the current sentence and preceding paragraphs. Secrets remain closed until the final page; some stay secret even beyond. The novels of Javiar Marías are doubly secretive, as the narrators in Marías’ books also know all — not always the case in novels — while the reader does not; and Marías wrenches as much tension as possible from that unbalanced relationship. The narrator in his 1992 novel “A Heart So White”: “The world is full of surprises and secrets. We think we know the people close to us but time brings with it more things that we don’t know than things we do.” Which is about as close to a description of a Marías novel as you’ll find in a Marías novel: We think we know the people in our lives. Alas, we don’t even know ourselves.

“Thus Bad Begins,” his latest, is overtly a book of secrets. “Yes, there are some fortunate people who never feel tempted to … put things right and confess,” confesses Juan De Vere, its narrator. “I’m not one of them, alas, because I do have a secret that I’ll never be able to tell a living soul, still less to those who have since died.” And thank goodness. Otherwise we wouldn’t have this erudite, strange, hypnotic and beautiful, frustrating book.

De Vere is 23-years-old at the time of the story, but more important, he is much older at the time of the telling — decades have passed since the story’s happenings, a long time, and yet still “less time than the average life, and how brief a life is once it’s over and can be summed up in a few sentences.” But of course DeVere’s sentence is ironic as he sums up only his brief time with a single family, the Muriels, mostly with its patriarch, and it takes 446 pages.

To step back: DeVere works as the personal assistant to one Eduardo Muriel, a semi-successful film producer and husband to the beautiful and tortured Beatriz Muriel. DeVere practically lives with the Muriels and their children in Madrid and witnesses the sadistic ways in which Eduardo treats his melancholic wife. Their marriage is terrible one.

The novel takes place in 1980, while Spain is transitioning to democracy after years under Franco’s rule (the ghost of Franco and his former regime haunt the book), and when divorce is still illegal. Their marriage is like a prison for Eduardo, though apparently far less so for Beatriz. By all accounts Beatriz still deeply loves her husband, but she has also committed some unnamed and unforgivable crime against him in the long past and is daily punished for her actions.

Eduardo verbally abuses Beatriz and refuses any offer of love from his wife. According to DeVere, Eduardo wanted to “make it clear to her what a curse and a burden it was to endure her presence; to mistreat and even abuse her, and certainly undermine her and make her feel insecure and even hopeless about her personality, her work, her body and he was doubtless successful.” And yet it is Eduardo who so disapprovingly describes an old “friend,” one Doctor Van Vechten, to DeVere: “…according to what I’ve been told, the Doctor behaved in an indecent manner towards a woman or possibly more than one. Call me old-fashioned or whatever you like, but that, to me, is unforgivable, the lowest of the low … Do you understand? That’s as low as one can go.” This from the man who regularly calls his wife a “fat cow,” “a pachyderm” and “a lump of lard,” who declares, “I might as well be touching a pillow, you might as well be an elephant, for all I care. A bag of flour, a bag of flesh.”

Thus comes the plot of the novel. DeVere, whose job normally involves taking notes, running errands and doing script translations, is asked by Eduardo to follow Doctor Van Vechten, to spend time with him, infiltrate his circle and get to know the kind of man he truly is. DeVere does indeed follow and befriend Doctor Van Vechten and in doing so becomes obsessed with Eduardo’s wife, Beatriz, as well. What had happened to make Eduardo so “indecent” to his wife; what brought him so “low”? Will DeVere find out Beatriz’s secret crime? And at what cost?

But then one doesn’t really read Marías for plot. One reads him for the language, the elegant hypnotic voice, the philosophical digressions and observations, for his long and winding sentences.

Here is DeVere (and Marías) on hands:

“I lit my cigarette and contrary to my usual habit — I always hold my cigarette in my left hand — I held it instead between the index and middle finger of my right hand and allowed my other hand, still holding my lighter, to fall on her thigh, which gleamed resplendent beneath the street lamps as they flashed past or beneath the intermittent moon. Not the palm, of course, that would have been cheeky, but the back of my hand. And not the whole of my hand either, but, initially, just the side or the edge, and then a little more as if my hand were giving in of its own accord or being jolted into position by the occasional bumps in the road or by the driver when he accelerated through a green light. It seems absurd, a hand is just a hand, but there’s an enormous difference between the back and the palm of the hand, the palm is the part that feels and caresses and speaks, usually deliberately, while the back pretends and is silent.”

The passage is prime Marías, close — bordering on obsessive observation of real physical movement that leads to a keen, and lovely, luminous poetic reveal. One reads Marías for his ability to make the smallest parts of the world come alive, and his penchant for philosophical narrative claims, ones that invite and require unpacking. Here is DeVere (and Marías) again on secrets: “That’s the trouble with secrets, one can never ask forgiveness.” Which of course makes secrets sinful. That DeVere certainly is we come to find out; and of course he is, he’s a Marías narrator.

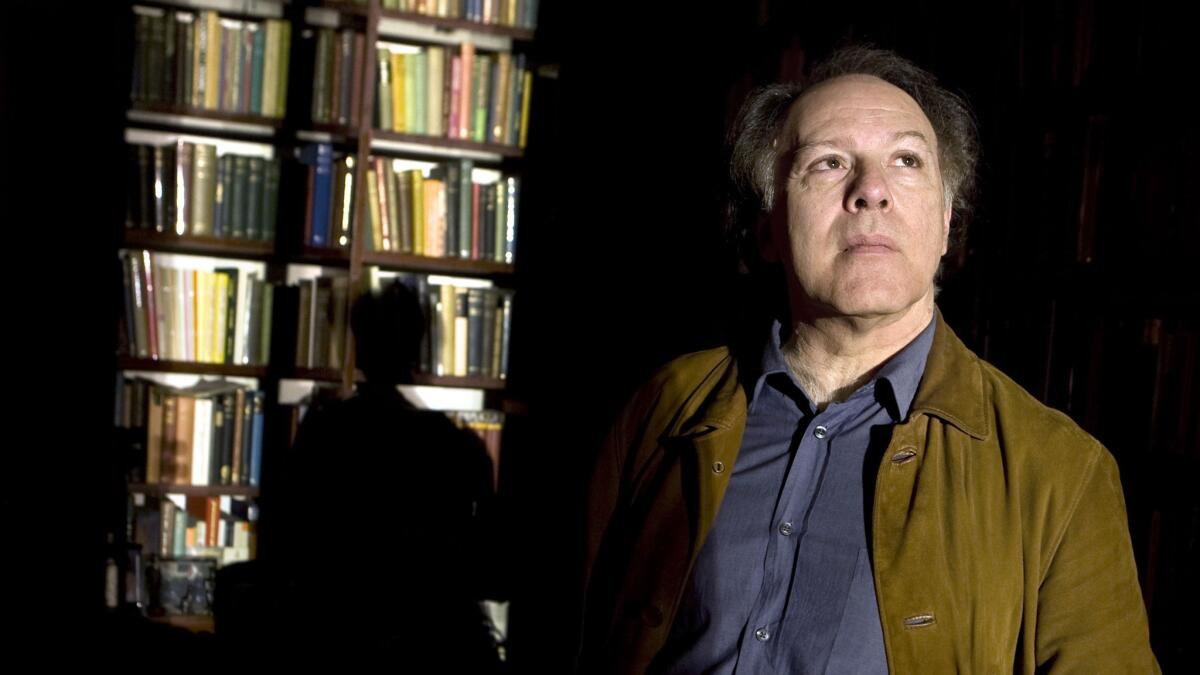

Marías, one of Europe’s favorite living writers, a perennial Nobel favorite and considered by many to be one of the greatest writers in the world, has according to some standards had trouble “breaking through” in the States. Others would say what nonsense.

“Thus Bad Begins” is a book for Marías lovers, a secretive novel, chock-full of fear and betrayal, but the stakes do only go so high. Classic Marías novels revolve around death, murder and violence, and perhaps it’s for that reason I found myself sometimes comparing it to his others. And perhaps it’s also for that reason I found myself most loving the book for its pages, brilliant observations, its musings and its suspenseful elegant voice, rather than the overarching story. And I could not put it down.

Cheshire is the author of the novel “High as the Horses’ Bridles.”

Javier Marías

Knopf: 464 pp., $27.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.