Review: ‘A Little Life’ a darkly beautiful tale of love and friendship

I’ve read a lot of emotionally taxing books in my time, but “A Little Life,” Hanya Yanagihara’s follow-up to 2013’s brilliant, harrowing “The People in the Trees,” is the only one I’ve read as an adult that’s left me sobbing. I became so invested in the characters and their lives that I almost felt unqualified to review this book objectively.

For example, less than 200 pages in, something wonderful happens to the main character, Jude St. Francis, who has already been subjected to an incredible amount of suffering. I became nauseous with the knowledge that this precarious joy would have to collapse in the following 500 pages. I wanted so badly for Jude to remain frozen in a moment of happiness that part of me wished the book were ending with that note of hope, the light reached at the end of the tunnel — I wished, in other words, for a gentler, inferior book. Instead, Yanagihara records the ups and downs of Jude’s life with painterly, painstaking patience, denying easy resolutions at every turn.

When the novel begins, Jude has already survived his formative traumas. He and college friends JB, Malcolm and Willem have moved to New York to realize their ambitions; he has a stable existence and people who love him. We meet him at a moment when a less exacting writer might have left him to a vague, sunny destiny.

But life for Jude is a daily struggle. He is overwhelmed by “the terrifying largeness, the impossibility, of the world, of the relentlessness of its minutes, its hours, its days.” His memories hound him, and he is in chronic physical pain because of a crippling injury of mysterious origin.

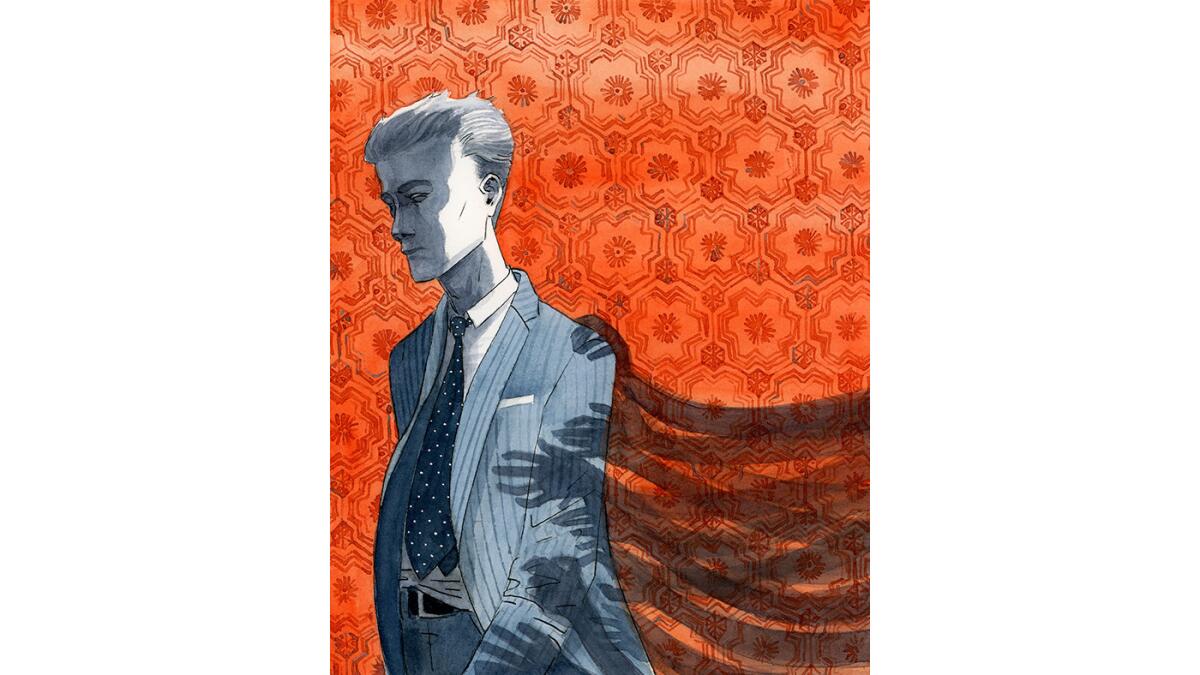

He doesn’t talk about his childhood, and he is constantly exhausted by “the thousands of little deflections and smudgings of truth, of fact, that necessitated his every interaction with the world and its inhabitants.” With endless vigilance, he hides his many secrets from his closest friends. At one point, JB dubs him the Postman: “[W]e never see him with anyone, we don’t know what race he is, we don’t know anything about him. Post-sexual, post-racial, post-past.” Even Willem, his most beloved, kind-hearted friend, finds that their relationship seems to require “not letting himself ask the questions he knew he ought to, because he was afraid of the answers.”

Yanagihara is a patient writer — she took nearly two decades to finish “The People in the Trees” while working as first a book publicist and later a magazine editor (she is an editor-at-large for Condé Nast Traveler). And while the narrative pace of “A Little Life” never feels sluggish, we learn about Jude in careful increments. (“Friendship,” thinks Willem, “was witnessing another’s slow drip of miseries.”)

Part of the suspense of “A Little Life” lies in our discovery of Jude’s horrific past, which Yanagihara reveals piece by excruciating piece. His childhood is an agonizing parade of tragedy and evil, starting with his abandonment at a monastery (“Inside a trash bag, stuffed with eggshells and old lettuce and spoiled spaghetti — and you”), where he suffers abuses at the hands of the brothers before moving on to worse and worse fates. But there is nothing lurid or gratuitous about the telling, and each piece helps us make sense of the Jude we have gotten to know.

We follow Jude and the people in his life for decades. (One of the many things Yanagihara handles well is the narrative passage of time.) He finds professional success as a fearsome litigator, and he maintains strong relationships that help him survive. He is beloved and cared for — by his friends; by his doctor Andy, who acts as a surrogate older brother; by his old law school professor Harold, who acts as a surrogate father — but his well-being is always in question.

Despite evidence to the contrary, he lives with the persistent belief “that he is a nothing, a scooped-out husk in which the fruit has long since mummified and shrunk, and now rattles uselessly.” He keeps his secrets close to his chest, convinced that he is “a person who inspires disgust, a person meant to be hated” and that his friends will reject and despise him if they find out what happened to him, which he can’t help but equate with who he is.

Here lies the central conflict of this novel — can Jude overcome his shame and self-loathing and open up to his friends? And if he can, will they be able to help him? It says a lot about Yanagihara’s talents that this deeply contemplative, psychological, tortured material is as compelling as the plot-heavy story of Jude’s past. It is also at least as upsetting, a brutal examination of the lifelong effects of trauma, of the impossibility of healing all damage.

“A Little Life” is not misery porn; if that’s what you’re looking for, you will be disappointed, denied catharsis. There are truths here that are almost too much to bear — that hope is a qualified thing, that even love, no matter how pure and freely given, is not always enough. This book made me realize how merciful most fiction really is, even at its darkest, and it’s a testament to Yanagihara’s ability that she can take such ugly material and make it beautiful.

Cha is the author, most recently, of “Beware Beware.”

A Little Life

A Novel

Hanya Yanagihara

Doubleday: 720 pp, $30

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.