Gary Shteyngart laughs away life’s ‘Little Failure’

I don’t speak a word of Russian. But I’ve come to believe some sort of strange symbiosis exists between the language of Tolstoy and the language of Shakespeare.

Russia gave birth to that master of English-language prose named Vladimir Nabokov. Half a century later, another writer who grew up with Cyrillic characters is gleefully writing American English as vivid, original and funny as any that contemporary U.S. literature has to offer.

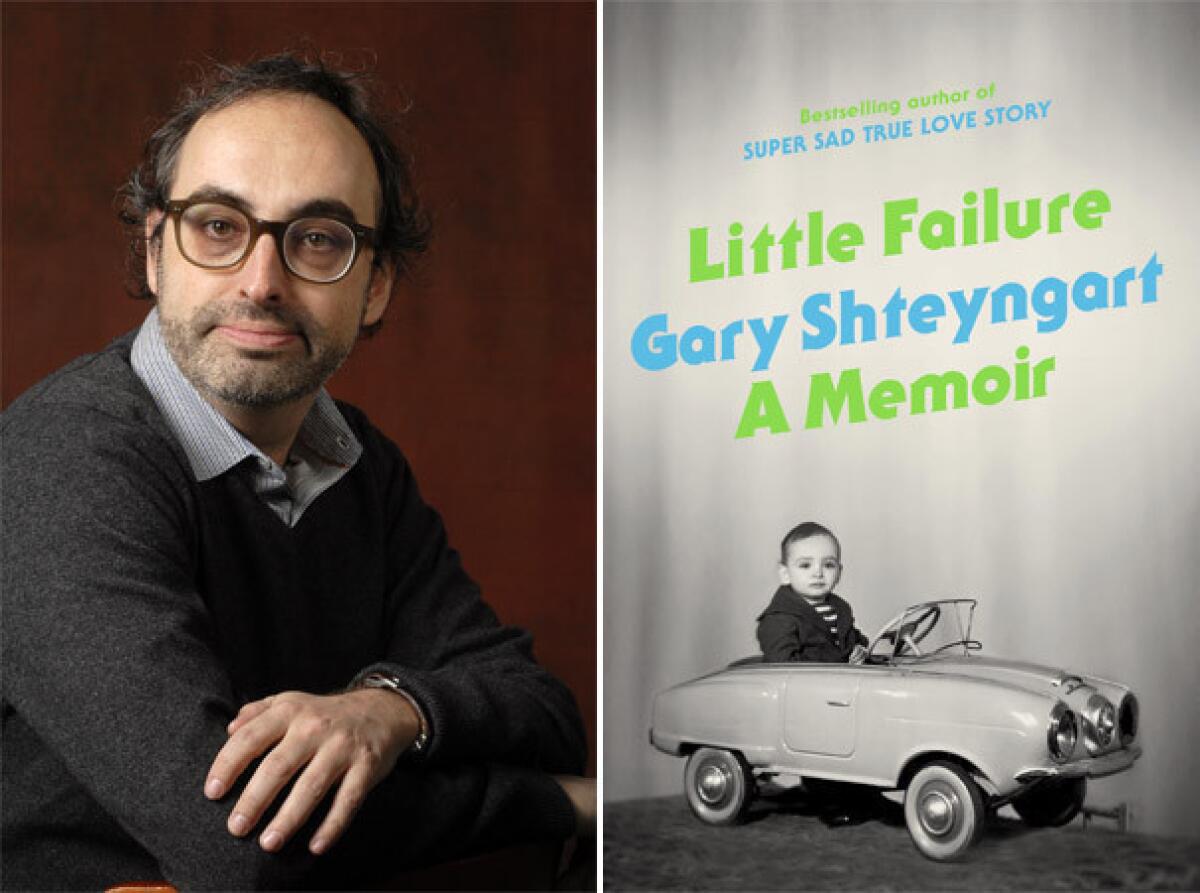

That writer is Gary Shteyngart, who wrote three excellent novels propelled by his ecstatic voice. In his fourth book, the memoir “Little Failure,” we learn how that voice was born.

Before he was “Gary,” Shteyngart was a boy named “Igor” born in a city and a country — Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and the Soviet Union — also fated to lose their names. The “evil empire” (as Ronald Reagan called it) was on its last legs, but the young writer-to-be could not know this. Igor dreamed communist dreams in which he slew fascist monsters. Real-life fun consisted of hide-and-seek with his father under the statue of Lenin near his home.

Instead of becoming a cosmonaut, however, or doing battle with the enemies of socialism, Igor left the USSR with his parents at age 7, then resettled in the U.S. and became Gary. Here, he battled Hebrew-school bullies in Queens, N.Y., and overcame the debilitating effects of a late circumcision (ouch!) to become a novelist.

“The past is haunting us,” Shteyngart writes early in “Little Failure.” “In Queens, in Manhattan, it is shadowing us, punching us in the stomach. I am small, and my father is big. But the Past — it is the biggest.”

To be Russian is to have a heavy past. But to be a Russian Jew, in Shteyngart’s telling, is to carry a past so weighty that only a good sense of humor can keep it from crushing you.

“As I march my relatives onto the pages of this book, please remember that I am also marching them toward their graves and that they will most likely meet their ends in some of the worst ways imaginable,” Shteyngart observes as he begins to describe the battles and executions of World War II that wiped out much of his extended family. His father became an orphan.

“’Oni menya lyubili kak cherty,’ my father says of those fleeting few years when both his parents were alive,” Shteyngart writes. “They loved me like devils. It’s an inelegant statement from a man who can veer between depression and anger and humor and joy with Bellovian flair.” The elder Shteyngart was too young when his parents died to really know them. Their love for him is “a belief,” Shteyngart writes, “and a near-holy belief at that.”

Shteyngart’s own parents and their epic story dominate his life and this book. The portrait of his father, an engineer with a romantic bent, and his music teacher mother is as full and complex as anything in his novels. Indeed, the emotional stakes seem weightier here than in his fiction, with Shteyngart using his linguistic and comic gifts to reveal the essence of a subject near and dear to him: himself.

In one of many flash-forwards to the present, Shteyngart reveals that he began this memoir after years in psychotherapy. Indeed, “Little Failure” feels a lot like a therapy session. Among other things, it’s brutally honest. When he begins writing it, his parents seem to know what’s coming. “How much longer do we have to live?,” his father asks.

The elder Shteyngart needn’t worry: He’s fully alive on these pages as is the rest of the Shteyngart family. After leaving austere Soviet Russia for anything-goes 1970s America, they are buffeted by culture shock, with young Gary getting the worst of it.

“A writer or any suffering artist-to-be is just an instrument too finely set to the human condition,” he tells us, “and this is the problem with sending an already disturbed child across not just national borders but ... interplanetary ones.”

The Shteyngarts are immigrants living an American dream of freedom and abundance — while trapped in a lifeless marriage. The angry father wallops his son, then plays board games with him, all the while exchanging colorful Russian insults with his wife in their small apartment. Gary remains an only child, he says, because “Russians don’t breed well in captivity.”

After Gary goes off to college, his mother realizes he isn’t going to make his immigrant parents proud by becoming a successful lawyer. So she gives him a Russian-English fusion nickname: Failurchka, or “Little Failure.”

In the hands of another writer, such a story might be maudlin. Shteyngart, however, isn’t capable of being anything but engaging, and his erudite, witty and self-mocking voice carries the day.

Eventually, the Shteyngarts move up in the world, buying a spacious home. But “Little Failure” isn’t about the ultimate triumph of capitalism.

Instead, its final moments of transcendence come in a deeply moving and uniquely Shteyngartian journey back to Russia. Traveling alongside his long-suffering parents, Igor/Gary closes a circle or two. And he allows his father to speak a few final words about an emotion born from many generations of suffering: guilt.

Little Failure

A Memoir

Gary Shteyngart

Random House: 368 pp., $27

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.