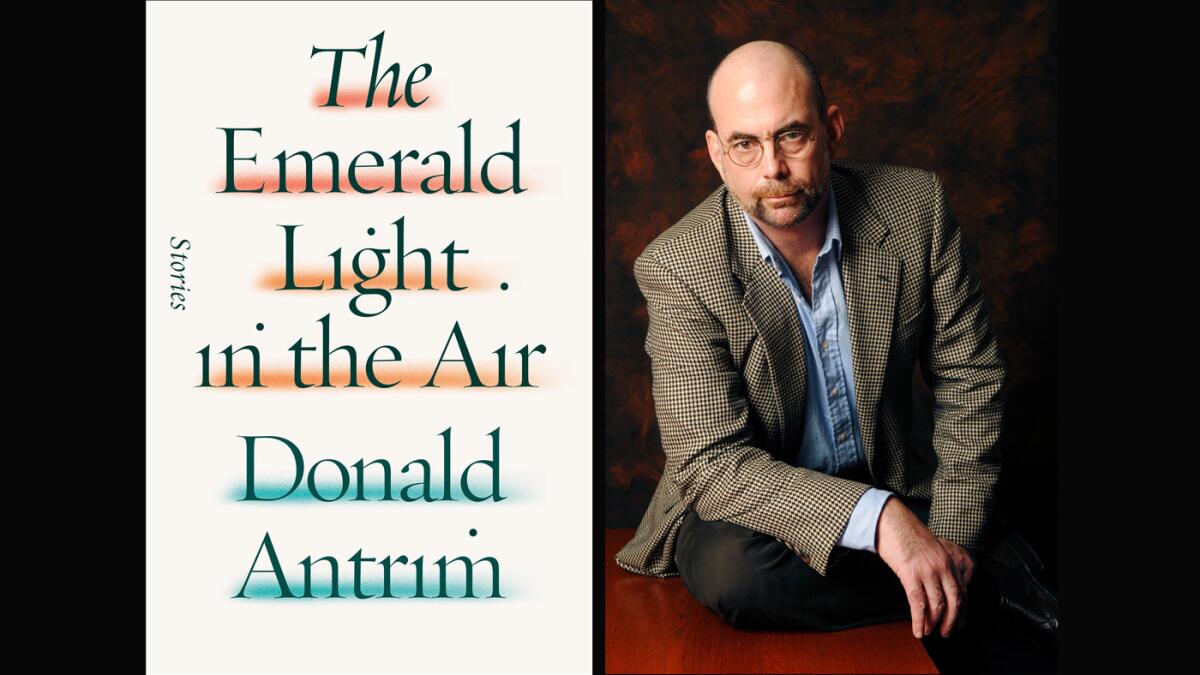

Review: Donald Antrim’s new story collection goes in unexpected directions

At first glance, Donald Antrim’s collection of short fiction, “The Emerald Light in the Air,” looks like a departure — at least from the three novels for which he is known. If in the past, Antrim has played around the edges of reality — his first book, “Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World,” involves a suburban town armed for self-defense, while “The Verificationist” unfolds in a pancake house where low-rent analysts lament their fates — here he plunges into the very center, describing a series of characters (men, mostly) lost in the middle of their lives.

In that regard, “The Emerald Light in the Air” is an extension of Antrim’s devastating 2006 memoir, “The Afterlife,” in which the author’s relationship with his mother becomes a lens through which to consider human frailty and dependence: all the ways we rely on one another, and all the ways that can never be enough.

This becomes apparent from the first story, “An Actor Prepares,” which opens with a typically Antrim-esque digression: a long paragraph, comprising a single sentence, riffing on Lee Strasberg and his advice about when (and when not) to rely on “the Emotion Memory.” The term, Antrim explains, refers to “the death of a loved one or some like event in the actor’s life that can, when evoked through recall and substitution, hurl open the floodgates, as they say, right on cue, night after night, even during a long run” — in other words, the essence of all art.

At the same time, there is a danger if an artist deploys these memories too soon. Strasberg suggests waiting seven years, but “Strasberg was wrong,” Antrim’s narrator, a fortysomething drama professor at a small liberal arts college, informs us. “Seven years are not enough, a fact I discovered recently during a twilight performance of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream.’”

“An Actor Prepares” is something of an antic comedy, not unlike “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” itself. In that sense, it’s of a piece with Antrim’s earlier fiction, which relies on the surrealism of daily life for its effects. Think of Donald Barthelme crossed with Don DeLillo: black humor with an existential edge. In the context of “The Emerald Light in the Air,” however, it’s also something of an oblique strategy, a bit of sleight-of-hand or misdirection that disguises the real concerns of the collection as a way of catching us off our guard.

I don’t mean to frame this as a criticism; in fact, it’s one of the most exhilarating aspects of the book, that it takes us in unexpected directions, moving from the outlandish to the intimate with the seamlessness of a single breath. “At first it appeared … inchoate and stagy — as if the artist had been playing with an idea about the drama in disorder,” Antrim observes in “Solace,” describing a character looking at an abstract work of art. “But the longer Christopher stared the more he felt compelled to see otherwise. … He felt the muscles around his eyes relax as his gaze became less focused; outlines of faces and figures receded into the drawing’s shadows, and the work acquired space and depth, interiority.”

That’s a pretty good description of how “The Emerald Light in the Air” operates, especially in a piece such as “Solace,” which opens the emotional terrain. The story of a couple who meet only in other people’s apartments (each has a difficult roommate situation), it becomes a still life of a relationship in stasis, on the cusp of a never-to-be-realized intimacy. “They were children of parents who’d acted grotesquely, some might say violently, toward them, even when they were fairly little,” Antrim notes, “and when, in their early thirties, they’d met and begun sharing confidences, their discovery of this common ground — for that was how she thought of it — seemed to her a great, welcome solace.”

This suggests that solace may be the best we can hope for — an idea Antrim raises again and again. In “Another Manhattan,” which involves a man struggling to maintain his grip between stints in a psych ward, or “He Knew,” with its portrait of another couple, this one married, who have found a bond in their disorders, he reveals an inner landscape of desperation, in which his characters are often barely holding on.

Depression is a theme, and also suicide, or not suicide so much as the threat, the possibility of it, like another form of solace to be called upon when the living gets to be too much. “Some days, he’d curled in a ball on the floor,” Antrim writes of the protagonist in the title story, “and promised himself that soon, soon, soon — it would be his gift to himself — he’d walk up to the barn and lie down with the rifle.” That he never does is something of a Pyrrhic victory: survival, yes, but at its own psychic price.

And yet, the title story is in its way the most upbeat in the collection, ending on a note of reconciliation, if not quite hope. As the final effort (and most recent: It like all of the stories here was originally published in the New Yorker), it suggests an arc or movement: from the surreal to the real. Indeed, the rural Southeastern setting, as well as the matter-of-fact evocation of a certain kind of desperation, reminds me of nothing so much as the work of Breece D’J Pancake, who wrote just a handful of bitter, brilliant stories before killing himself in 1979 at age 26. These aren’t two writers I generally think of in the same breath. But that, I’d suggest, is the point precisely, an indication of how close to the edge Antrim means to take us — and himself — in “The Emerald Light in the Air.”

Follow me on Twitter: @davidulin

The Emerald Light in the Air

Stories

Donald Antrim

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 176 pp., $22

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.