Alexander Chee’s guilty reading pleasure: Tom Ripley

A few months ago, I found myself reading, at last, Patricia Highsmith’s “The Boy Who Followed Ripley.”

I had meant to read it before this — I’d fallen for Ripley, you could say, like many. And then, I’d drifted off. But now, years later, like many, I was desperate to break the spell, to read anything else other than the news, and get lost in that instead. I just needed a break in the horror, and something that wasn’t misspelled by the president, or by someone imitating his misspellings.

I’d read “The Talented Mr. Ripley” and “Ripley Under Ground” a few years ago, and watched both film adaptations — “Purple Noon,” and then the eponymous Anthony Minghella picture, starring Matt Damon, Jude Law and Gwenyth Paltrow.

I had even come to an understanding of that first novel that gave me the twinge I get when I might begin writing a novel of my own: Marge, the original Tom Ripley’s girlfriend, is a writer to no purpose in the plot. It does not matter, at all, to the story. She is essentially there to be made a fool of — and to scream the alarm that Ripley has killed Dickie, so that it is all the more frightening when he gets away with it. For a writer as deliberate as Highsmith, who even wrote a book on how to write suspense, that makes this detail potentially something of a tell — a detail left over from an autobiographical episode, included because that is how it happened. I have no other proof of this, other than a life spent writing and teaching writing. And that the novel is easily an expansion of her theory of what happened, what she believes as she rages at Ripley by the end. It was easy to imagine Marge returning to New York and writing this novel — it could even have been her way of telling him she knew this to be true.

When I turned to “Ripley, Under Ground,” next, I read it in part to see if my theory held up. That novel I found to be an entertaining if somewhat lighter art forgery novel, with desperate moments. Years after I read it, I came across a story of an art forgery ring in a small town in France that operated with details familiar to anyone who’d read the novel. And while these details could be the details of any art forgery ring in France, the strange half novel I was writing in my mind picked up again, and I imagined my fictional Marge/Highsmith continuing to follow the murderer, and writing more of these novels as a way of telling him she knew what he was up to, even if no one believed her. When I thought of what Ripley might feel, finding a novel about himself by her, I understood also that it was potentially a game he would not want to bring to an end, because perhaps being known this way would be the only intimacy someone like Ripley could allow. I then imagined an heir — a protégé or offspring who comes into possession of evidence of this after the writer’s death — but the idea came to nothing, and I let the trail of my novel idea go cold there.

Recently, desperate to escape the horror of the news, I found myself reading the reviews of “The Boy Who Followed Ripley,” on Amazon, and the complaints, insisting the novel was slight, were so interesting that I decided it was time to return to Highsmith’s most famous creation and the strange universe I was building around him. And so, I bought the novel, and went back in.

Who follows whom

“The Boy Who Followed Ripley” is the penultimate Ripley novel; the loneliness of a murderer is most certainly the topic. There is even a protégé. Set several years after “Ripley Under Ground,” we find him a happily married man, living in that small town outside Paris, where he is content to manage the production and sale of his successful art forgeries in a way that is designed not to attract suspicion. His wife, Heloise, is French, independent, mostly incurious about the specific details of her husband’s profession because she is an heiress; the detachment with which she regards him is almost exotic by our standards of marriage. He is living a happy country life, essentially untroubled, until the day his neighbor’s gardener walks down the road.

The handsome young gardener introduces himself as Billy Rollins, an American. He is quickly revealed to be a millionaire with a secret: His real name is Frank Pierson, he knows Ripley is selling these suspicious paintings, as his father had collected one, and his own sleuthing into the painting’s provenance has led him here.

Another secret is soon revealed: Frank is also the subject of an international manhunt. His father fell off a cliff while his son was with him at his home in Maine, and although Frank is not believed to be the murderer, he confesses he is after a few long talks with Ripley. And at first, Ripley believes him. And so begins an obsession that lasts the length of the novel. He tries to save Frank from himself by teaching him how to be like him. Or something like him.

I’d fallen for Ripley, you could say, like many. And then, I’d drifted off. But now...I was desperate to break the spell, to read anything other than the news

The novel would perhaps be more properly called “The Boy Ripley Followed.” Ripley helps him hide from authorities, even gets him a new passport and a new name. The incurious Heloise grows curious as her husband soon seems obsessed with taking care of Frank’s every need, even asking if he’s in love with him. They run off together to Berlin for a few days, meant to cheer Frank up, and they do seem to be so clearly in love — and yet Ripley, if he knows it, seems oblivious to it. But perhaps not Frank, who recoils with despair at any attempt by Ripley to get him to return to America and his life there. He longs only to be in Europe with the art thief he’s caught. The novel’s clearest irony is that this young man did what he did to escape a domineering father — only to find another one in Ripley, who tries, very hard, to control every aspect of his life.

In Berlin, after a few adventures, Frank is kidnapped and Ripley rescues him, deciding on a madcap escape that includes dressing in drag, as a disguise, to no apparent purpose in the plot, except that it provides us with a lavish visit to a gay club. And here for me was the escape I did not expect, to 1960s Berlin, and a glimpse of those people, in that city. I almost did not care that these lovers never seemed to kiss. I almost didn’t care what happened next in the story. For one of the first times in my reading life, I found I wanted the set more than the story.

My favorite part of the novel is when Ripley arranges a meeting with the kidnappers at a club called Der Hump and invents a drag name for himself on the spot.

“‘And who are you?’ asked a young man in Levi’s so worn out, they revealed the absence of any underwear. ‘Mable,’ Tom said.”

Ripley soon realizes he hasn’t bothered with nail polish, and ponders the appearance of the other guests he can see in “long dress drag,” flirting with a man named Rollo, also in drag, and then dancing with him, barefoot, in the disco. And this was when I realized I had fallen, deeply, just as I’d wanted, out of the one world, into this one.

Ripley re-imagined

I understood the reviewers. When we eventually left Berlin, I was almost as crushed as Frank, who didn’t want to leave, much less go home. I even expected him to reveal he was the kidnapper, and that he was setting up a secret life for himself with the money. But this was not the story.

Instead, Ripley goes to such extraordinary lengths to rescue Frank that the family insists on meeting him, and soon Ripley heads back to the U.S. with the wayward Frank, intent on getting him to return to his life and live with the murder of his father. He tries various attempts to force Frank to deal with what he doesn’t want to deal with, insisting the young man can go home and carry on as if the murder didn’t happen. This being Highsmith, there are a few last tragic turns, and after the ending, I pondered the life of a young man who had gone to France to escape the horror of his tiny life, only to be taught by someone he imagined would understand his own need to escape and reinvent himself, and who, instead, despaired as his idol became like the father he’d hated.

My own desire to escape and reinvent, to leave this one world for any of the ones I kept building alongside this one, left me a little like the disappointed reviewers, in that I also had written in the kiss between the lovers that never happens. But my own, imaginary, unwritten novel turned to this: Would my imaginary Highsmith be trying to tell her Ripley that his only intimacy was with someone else who had also murdered someone — that they were the only two who could understand each other? Ripley fosters a connection to Frank unlike any the other has with anyone else in their lives. There’s a reason Ripley’s wife is jealous — Frank knows him in a way she never will.

A character like Ripley fascinates because he is one of those protagonists who doesn’t much change — the novel’s transformation is enacted inside the reader. You are the one who changes, confronted with the baroque moral surface of a murderer’s loneliness. I’ll read the last one next, the one I skipped also, continuing my little game to its end. What is visible to me now is how another novel, the one all of this curiosity is really feeding, will likely appear then.

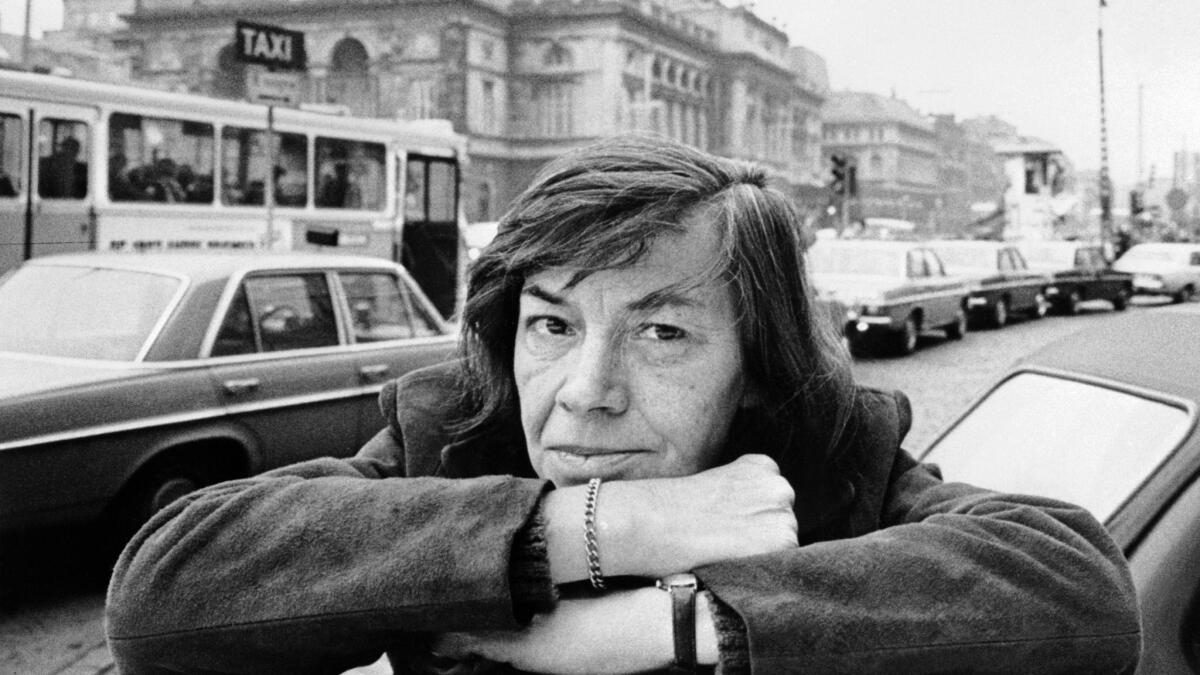

Chee, one of The Times’ critics at large, is an assistant professor at Dartmouth and the author, most recently, of the novel “The Queen of the Night.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.