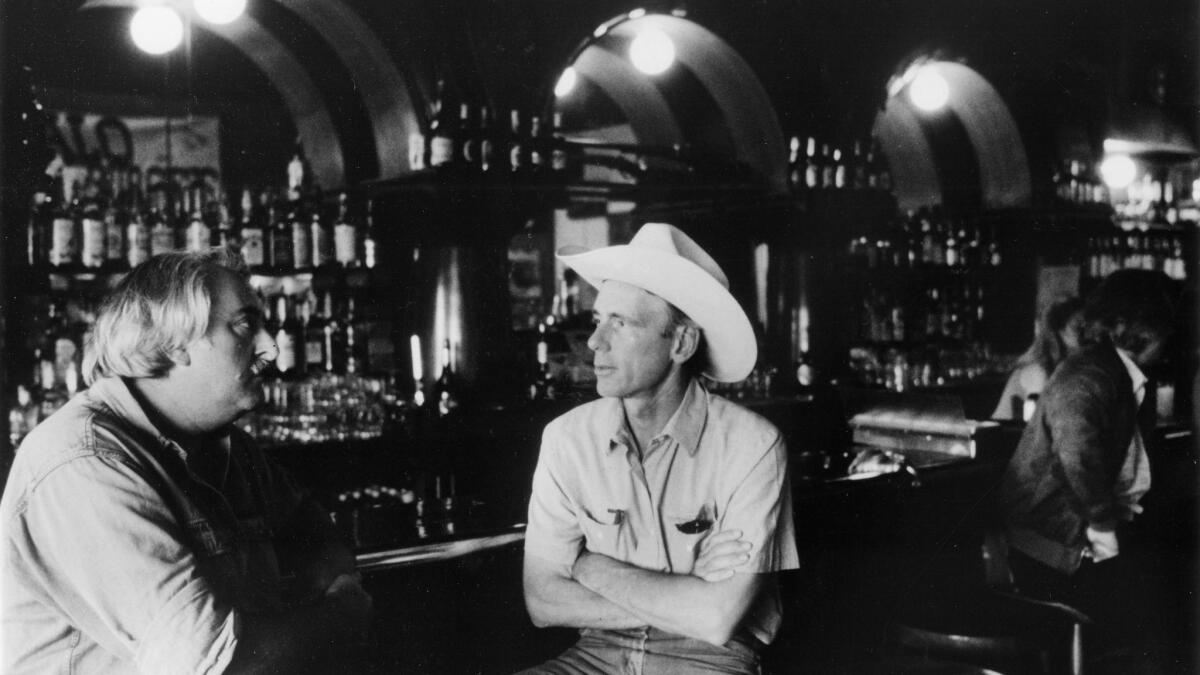

Thomas McGuane, winner of the upcoming Kirsch Award, on his path as a writer

Thomas McGuane wants to discuss how fiction works. It’s a Friday afternoon, and he’s on the phone from Florida, where he recently hosted a family gathering: “all the kids and grandkids,” as he puts it, a tone of satisfaction in his voice. Now, the family is gone and he’s considering the trade that has defined him for half a century.

“It’s like being in the woods and trying to start a fire with wet kindling,” the 77-year-old — who will receive this year’s Robert Kirsch Award for lifetime achievement at the Los Angeles Times Book Prizes — explains with a light chuckle. “You keep breaking matches and you are shocked when it lights.”

Such a description is as clear an evocation of the writer’s process — with its fits and starts, its leaps and minor acts of faith — as one can imagine, suggesting that a successful novel or short story is less a product of intention, exactly, than of some combination of perseverance and good luck.

“Take my story ‘The Casserole,’” McGuane continues, referring to one of the pieces collected in “Crow Fair” (2015), his third book of short fiction. “I started with the wife. I wanted to write about how life was tiresome for her. I had the idea that she was having an affair with an airplane pilot, but that never made it into the story. This, to me, is what’s so attractive about writing fiction; I get taken for a ride. I look back and picture what I was going to write, and I’m amazed at how it ended up.”

Thomas McGuane will be at the LA Times Festival of Books on April 22nd at 4:30pm. »

The same, of course, is true for us. “The Casserole” offers a case in point: a very short story, sketch-like almost, about the precise instant that a marriage ends. The twist? Only one member of the couple knows what’s going to happen — until the astonishing final paragraphs. “I turned to Ellie,” McGuane writes. “Tears filled her eyes. I felt that this could have been handled in another way — without Dad’s hand on the gun, and so forth. I think, at times like this, your first concern is to hang on to a shred of dignity.” As it often is in McGuane’s work, the voice is everything: understated but also a bit befuddled, as if the narrator had been caught unaware. “It’s the way I work,” the author says. “Something won’t leave my mind. I’m interested in how these dissonances come to light.”

Dissonance is a good word for the pressure points of McGuane’s fiction, the fissures and dissatisfactions he seeks to explore. It’s a territory he has mined in one way or another since his first novel, “The Sporting Club,” which he wrote in six weeks while a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, appeared in 1969.

“The Sporting Club” is a tale of decline and corruption at a Michigan resort; it is a social novel rather than a personal one. Similar impulses guided McGuane’s next two books: “The Bushwhacked Piano” (1971), a comic novel of the road, and “Ninety-Two in the Shade” (1973), the saga of a Key West fishing guide that was nominated for a National Book Award and is regarded by many readers as his masterpiece. “Nobody knows, from sea to shining sea, why we are having all this trouble with our republic,” McGuane begins the book — a line, he admits, that “makes me feel prescient,” although he takes little joy in it. “These are terrible times,” he says. “The country is imperiled. It was imperiled when I was writing ‘Ninety-Two in the Shade,’ but there was such free-floating optimism in the culture. America still felt like a place to re-create yourself.”

After “Ninety-Two in the Shade,” however, McGuane shifted direction, working for a while in Hollywood (he wrote the screenplay for the 1976 Jack Nicholson-Marlon Brando vehicle “The Missouri Breaks” and directed his own adaptation of “Ninety-Two in the Shade”), even as he went through a series of personal upheavals, including the breakup of two marriages and the deaths of his parents and his sister. When he returned to fiction, with the 1978 novel “Panama,” he was a different writer — or, at least, one with a new set of concerns. “I look back at ‘Ninety-Two in the Shade,’” he laughs, “and I think: It took guts to write that recklessly,” although what he’s remembering is the joy of pushing against the limits of language and form. With “Panama,” he turned inward, writing about a musician dealing with the fallout of his fractured life. “As time goes on,” McGuane insists, “private life looms larger because the outside is so hard to control. The personal becomes an area, maybe the only area, in which you can do something that will change your world.” Equally important is his impatience with what he once dismissed as “showing off in literature.” Asked to elaborate, he answers simply: “I became less interested in wasting readers’ time as I played.”

In part, McGuane concedes, this has to do with Montana, where he has lived since the days of “The Sporting Club.” At the same time, he resists defining himself as a western writer, even though his work has engaged the region for more than 30 years. “Yes,” he says, “I am a Westerner in the sense that this is where I’ve lived the bulk of my life, and raised my family, and paid taxes and voted and buried so many dogs and horses. But I’m also looked askance at, or looked at with suspicion, because I’m not interested in exhausted archetypes. One of the strains of writing in the West is that you’re seen as betraying local tradition if you write about a pizza delivery boy or any of the people you actually see.”

McGuane, of course, is not alone in tracing this conundrum. As far back as 1968, Larry McMurtry was making a related argument in his book “In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas.” “The myth of the cowboy,” he wrote there, “grew purer every year because there were so few actual cowboys left to contradict it.”

Nonetheless — and perhaps because he is a transplant rather than a native — McGuane feels less conflicted or constrained. It’s been seven years since his most recent novel “Driving on the Rim,” but he’s not counting; he’s focused on making short fiction instead. “When I was at Stanford,” he recalls, “Wallace Stegner told me, ‘Why write a short story when it could be a chapter in a novel?’ I was young, and wondering how to make a living, and I thought, ‘Maybe he knows what he’s talking about.’” And yet, McGuane continues, “a story has as much of an emotional payoff as a novel. It has to do with the the pristine lyric language, the concision of the narrative.” Indeed, it’s hard for him to envision working on a novel now. “It would have to surprise me,” he acknowledges. “I can’t imagine wanting to do more or better than a short story. The best stories, I think of them as apertures. They’re how the dissonances come to light.”

David L. Ulin is the author of “Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles.” A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.