Laughs flow from James Burrows’ direction

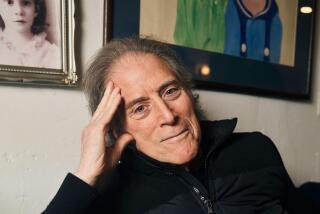

At a recent studio taping for the new CBS sitcom “Mike & Molly,” a bald, slightly built man with a fringe of white hair prowled behind the cameras, listening intently, every so often hollering out to the actors as they performed a scene. If a line reading was flubbed, he was on it before the last word had left the actor’s mouth.

“I’m not hearing it!” he cried. “Do it again, from the top.” And later: “Louder, louder!”

CBS has a lot riding on James Burrows and his finely tuned ears. The most successful director in TV comedy history (his hits include “Cheers,” “Friends,” “Will & Grace” and “Two and a Half Men”), Burrows has a fabled ability to tease cozy, living-room-ready life out of the black-and-white words in a script.

Much of what audiences instantly recognize as a network sitcom style -- brightly lighted soundstages, a four-camera setup, emphatic line readings, punch lines tossed out as a character enters or exits a scene -- Burrows played a key role in developing. But what he’s especially good at doing is fostering a warm sense of family among the actors and the viewers -- a difficult quality to analyze and therefore to duplicate.

“The humanity you feel with one another comes across,” he said of his cast, “even though you’re playing characters in conflict.”

Chuck Lorre, an executive producer on “Mike & Molly” who’s frequently worked with Burrows, explained the director’s approach: “Jimmy can hear the music in his head.”

Burrows is the acknowledged master of the multi-camera sitcom, which is shot in a studio, usually before a live audience. It’s a theatrical style, a throwback to TV’s earlier times àla “I Love Lucy.” The trend runs counter to TV’s current obsession with so-called single-camera (read: movie-like, no audience or laugh track, often shot on location) comedies. The biggest comedy hits from last season -- ABC’s “Modern Family” and Fox’s “Glee” -- are both single-camera.

CBS has stuck to the multi-camera genre even as rivals have drifted away. And it’s been rewarded handsomely with the hits “Two and a Half Men” and “The Big Bang Theory,” both from the busy Lorre workshop. This season, with “Big Bang” moving to Thursday, executives are putting “Mike & Molly” on Mondays, in a key slot behind “Two and a Half Men” and before “ Hawaii Five-O,” their big drama bet for the year. Ratings for last week’s premiere were encouraging: An average of 12.2 million total viewers tuned in, according to the Nielsen Co.

CBS needs the new comedy to work. Having Burrows helm the entire first season is probably the best insurance policy a nervous network can buy. “That guy has forgotten more funny than most of us ever know,” said Billy Gardell, the star of “Mike & Molly.”.

“Mike & Molly” -- a romantic comedy about a sarcastic yet insecure 300-pound Chicago cop (Gardell) who falls for a zaftig schoolteacher ( Melissa McCarthy) -- has already kicked up controversy about its approach to obesity. Yes, it has two overweight leads who meet at an Overeaters Anonymous gathering. Many critics have commended that as an antidote to unrealistic beauty standards everywhere else in prime time. But the show also has, er, a ton of fat jokes. Is “Mike & Molly” trying to have it both ways on size acceptance?

Burrows, 69, takes the issue in stride. “I remember on the pilot of ‘Will & Grace,’ when one of the NBC executives came over and said, ‘There’s too many gay jokes,’” he recalled in his second-floor office above the Warner Bros. soundstage in Burbank. “I said, ‘If not here, where?’”

As for “Mike & Molly,” he said, “There may be a few too many fat jokes in the show … [but] it’s not what the show’s about.”

Out of the mouth of someone else, that might sound like typical spin. But Burrows is the closest thing TV comedy has to Obi-Wan Kenobi. His creative skills, along with his golden résumé and unassuming nature, have bestowed on him a reverence unusual for someone working in Hollywood’s trenches. As Lorre joked, “I’m so glad you’re doing this piece. It will really help his career.”

Mark Roberts, a longtime Lorre protégé who created “Mike & Molly,” said that Burrows hears sitcoms almost as radio plays, which makes a certain kind of sense. The director’s father, Abe Burrows, was a legendary writer and performer in the twilight years of radio comedy in the 1940s, before TV took over. The elder Burrows later co-wrote the books for the Broadway musicals “Guys and Dolls” and “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” and became familiar to viewers as a panelist on “What’s My Line?” and “The Match Game.”

The inevitable comparisons with his famous father -- who died in 1985 -- may have pushed Burrows away from writing. “My father was weaned on books,” he said. “I’m halfway between being weaned on books and weaned on television. And if you’re weaned on television you’re not as good a writer as if you were weaned on books.”

But directing is another matter, using a related but quite different skill set. “I know what’s funny, and I probably know the best way to deliver the joke. Whether it’s walking out of a room, facing that way, facing this way,” he said. “I just have a sense of that.”

After a stint at the Yale School of Drama, Burrows was directing theater in the early 1970s. He had met TV producer Grant Tinker and his then wife, Mary Tyler Moore, during an earlier stint as a stage manager for a show Moore was appearing in. So he wrote Tinker and Moore -- who by that time were doing “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” -- looking for a job. By the end of the decade, he was regularly helming episodes of ABC’s sitcom hit “Taxi.” His string of hits since then has made him not just one of the most respected directors in Hollywood but also one of the richest. Unlike most TV directors, he has the clout to take a financial stake in the shows he oversees and enjoys an enormous windfall if they become hits, as in the case of “Friends.”

For someone who’s spent his life in comedy, Burrows is surprisingly low-key. During interviews, he’s polite and unassuming but rarely cracks a smile and doesn’t feel the urge to fill a silence with the sound of his own voice. During tapings, with the writing team hunched over the monitors, Burrows paces apart from them, often looking down. It can seem as if his mind is elsewhere, but the ears are always engaged. At the session for the third episode, he called out McCarthy for underplaying Molly’s reactions after she handily beat Mike at bowling.

“The second something’s slightly, slightly off, you see him turn right around,” McCarthy said. “You can’t get anything by him.”

Burrows said there’s a reason he reacts so quickly: “Sometimes an actor will stumble on the joke, and I’m right on them. Back it up before the audience hears the bad version of the joke, because humor is 90% surprise. If they know what’s coming, they won’t laugh as hard.”

When a joke worked, however, Burrows would sit slumped in his director’s chair, giggling like a frat boy. Since he already knows the script cold, he was not laughing out of surprise. Rather, it was an unspoken signal, one that the actors live to hear. The signal meant that the scene is working. They made Burrows laugh.

For actors, “I’m the guy that wants you to walk the comic plank for me,” he said. “Take it as far out as you want to take it and I’ll bring it back. Sometimes I’ll take it further. But trust me.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.