Review: ‘Shutter Island’

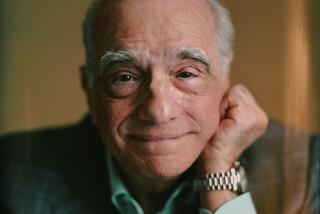

In “Shutter Island,” director Martin Scorsese has created a divinely dark and devious brain tease of a movie in the best noir tradition with its smarter than you’d think cops, their tougher than you’d imagine cases to crack and enough nods to the classic genre for an all-night parlor game.

It’s 1954, the heart of the Cold War, with a conspiracy theory around every corner, when Leonardo DiCaprio’s U.S. Marshal Teddy Daniels and his new partner, played by Mark Ruffalo, are dispatched to an asylum for the criminally insane to investigate a dicey disappearance. One of the facility’s most notorious patients, a young mother who drowned her three children, has somehow vanished from a room monitored 24 hours a day, its door bolted from the outside.

But there are deeper mysteries here, and Scorsese has a lot more on his mind than one crazy inmate on the loose. The A-bomb threat is ever present, memories of Nazi death camps linger and rumors of questionable scientific experiments by the asylum’s doctors are circulating. Though the more central question, gathering force like the coming hurricane, is the very nature of sanity and insanity.

Bit by bit, the filmmakers begin to shift all that trouble onto Teddy’s shoulders, already weighed down, we’ve been told, by the death of his wife and the knowledge that her killer is an inmate at the asylum.

But Teddy’s problems are never too much for Scorsese and DiCaprio, who in their fourth collaboration have developed an ease evident in every scene. Here the actor slips so deeply inside Teddy’s skin that it allows his anxiety to creep under ours, while the director makes the most of that naked vulnerability, moving the camera in so close we can see the look in his eye, and that is unsettling indeed.

All the action takes place on a remote island off the Eastern Seaboard where Ashecliffe Hospital sits, with the sinister look of things serving to ratchet up the sense of jeopardy. Dante Ferretti, in his seventh film with Scorsese, sets the stage with his production design, the asylum itself a looming Gothic architectural throwback that never looks less than intimidating. There is a carefully orchestrated soundtrack from another of the director’s pals, singer-songwriter Robbie Robertson, literally coming in with a crescendo every time you feel the urge to whisper, “Cue ominous music.”

Between the psychopaths, the psychiatrists and the skeletons in Teddy’s closet, the line between reality and delusion, sanity and insanity, soon begins to blur. It is here that the film really begins playing around with the psyche, both Teddy’s and ours, though the agenda is laid out from director of photography Robert Richardson’s first images of Teddy reeling from seasickness in the claustrophobic latrine of the prison ferry on the ride over -- tortured eyes looking back at us from the mirror as he splashes water onto his face.

Water is an image Scorsese returns to again and again -- the ocean that isolates the island, the relentless hurricane that rages down, the drowned children of the missing inmate. Peril, rather than life-sustaining, seems to be the relevant allegory here, so you soon start worrying when anyone turns up wet.

Using noir’s narrative style, often to brilliant effect, it is pure pleasure to watch as Teddy parries with his partner, the hospital staff led by Dr. Cawley (Ben Kingsley), the inmates or the security detail, with John Carroll Lynch particularly good as the brick wall of Deputy Warden McPherson. It’s probably never better than in a confrontation with the shadow king of Ashecliffe Hospital, Max von Sydow’s Dr. Naehring, Teddy throwing down hypotheses suggesting his guilt like a gauntlet, Dr. Naehring deflecting each one with bemused irony.

In its own way, Laeta Kalogridis’ screenplay, which is based on the Dennis Lehane bestselling novel, turns into Teddy’s most formidable adversary -- never letting him rest as obstacles are thrown in his path and paranoia rises with every step he takes.

We’re pulled deep into a maze so complex it threatens to cloud the story, beginning with Teddy’s tortured memories of his wife, Delores (Michelle Williams), and the migraines that plague him, to say nothing of his World War II soldiering days, including the liberation of Dachau and the horrors that implies. When the missing patient (Emily Mortimer as the younger Rachel, Patricia Clarkson the elder) mysteriously turns up, Teddy’s gut tells him a lot of questions remain. As if by design, the hurricane finally blows in, cutting off access to the mainland and creating a dark and stormy night filled with scary sounds, ideal conditions for sleuthing around all those off-limits areas that any decent insane asylum has. While it’s clear Scorsese is having great fun tightening the screws at every turn, some of the psychological tension that should have the crackle and shock of electricity in a thriller like this is lost in the crowd.

There is always a sense that Teddy’s running out of time, and for a while we don’t know exactly why. Once we do, Scorsese sets about tidying things up a bit too fast, like a college professor who knows he’s got to let the class out, so let’s just get through this, shall we.

Whether it’s a rushed dénouement or a tendency to overindulge in delusions, the flaws are never enough to do permanent damage to the film. Ultimately, Scorsese has given us a new noir classic, though watching Di- Caprio’s Teddy twist in the wind while his mind unravels would be satisfying enough.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.