Remembering the Chicano Moratorium

Last Friday evening, in an East L.A. living room, a group of musicians gathered to discuss finishing a concert that ended prematurely, and tragically, 40 years ago.

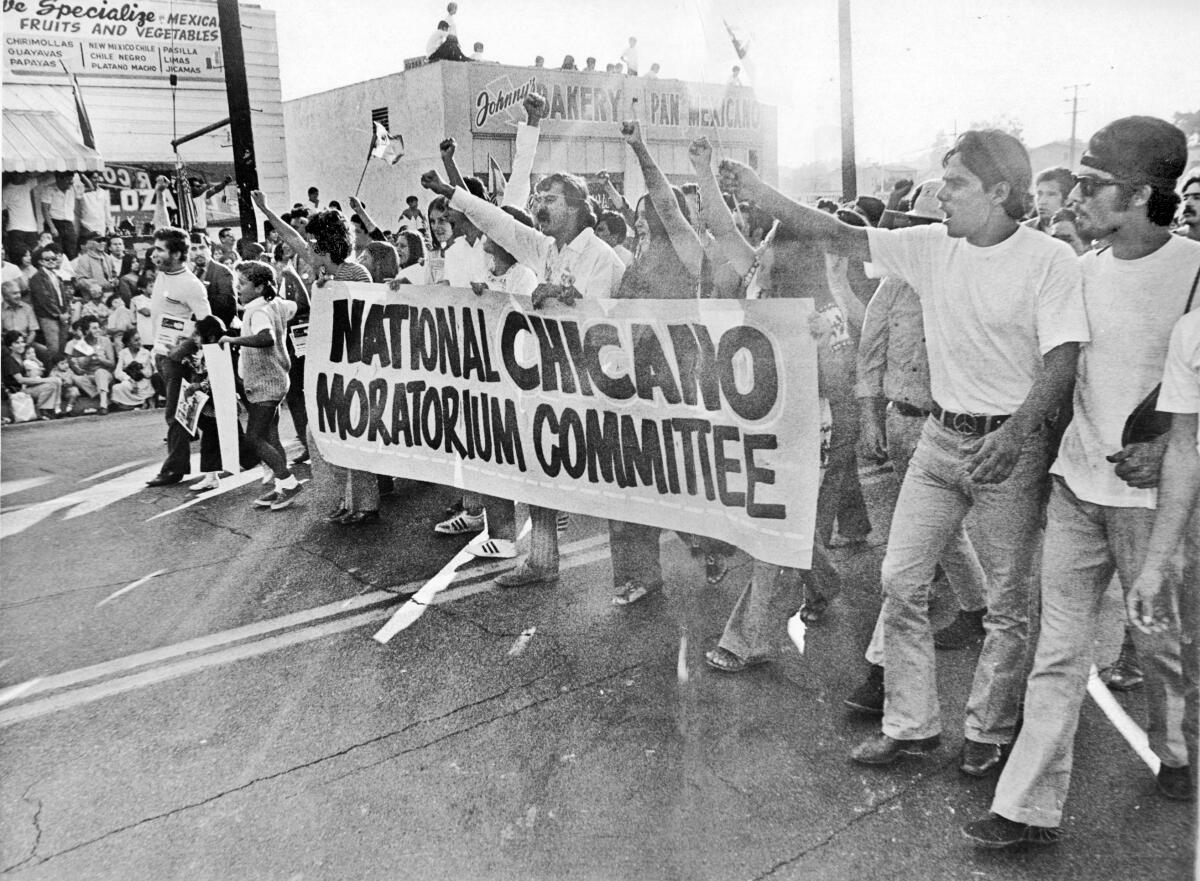

Willie Herron III and Jesus Velo of the Chicano punk-new wave band Los Illegals and their friend Rudy Salas of another legendary Chicano group, Tierra, were teenagers and young men on Aug. 29, 1970. That was the date, among the most significant in modern Mexican American history, of the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War.

An estimated 30,000 people marched that day through East Los Angeles in what began as a peaceful, festive get-together, with songs in the air and young and old united in chanting political slogans.

“It was so beautiful, when you were there,” recalled Salas, a guitar player. “They had music there and it was a family-oriented type of situation.”

But the day ended in a flurry of beatings and flying objects when law enforcement officials clashed with marchers, and three people were killed. Among those slain was Los Angeles Times reporter Rubén Salazar, whose columns had championed Latino rights. He died after being struck by a tear gas canister fired by a sheriff’s deputy into the Silver Dollar Bar.

In the days that followed, the march helped to galvanize Mexican Americans politically and culturally, not only in Los Angeles but in the United States as a whole. “People talk about 1968 as a flashpoint for change in America,” Velo said. “For Chicanos, it was 1970.”

On Saturday, at East L.A.’s Belvedere Park, Los Illegals and brothers Rudy and Steve Salas of Tierra will be among the bands and performers paying homage to the moratorium’s 40th anniversary and celebrating its enduring legacy. The free all-day event will include a photo exhibition documenting the Chicano Moratorium and a 2 p.m. rock concert, emceed by music-historian authors David Reyes and Tom Waldman, that will spotlight some of the musicians who were slated to perform that day in 1970 but never got to play after the melee broke out. Other performers will include Mark Guerrero and CAVA.

For some participating artists, the occasion evokes mixed feelings. On the one hand, bitter memories linger: Ghostly tear-gas clouds. Panicked children running and screaming. The thud of body blows. Whittier Boulevard on fire. While specifically targeted at the Vietnam War, and the swelling numbers of Latinos who were serving and dying in it, the moratorium also expressed the community’s growing frustration over its lack of economic and political power.

Velo said that on that day, he was working as a volunteer driver for the Mexican-American Political Assn., shuttling out-of-town visitors from LAX to East L.A. When violence broke out, he parked his car and went to hide in a friend’s basement, listening to Bob Dylan, Beatles and Pete Seeger records.

“That’s how I rode out the evening, hiding from the police,” he said. “They were just patrolling the street, beating everybody up.”

Salas’ entire family took part in the moratorium. He remembers that a pair of newlyweds left their wedding party to join the march. “It was that kind of atmosphere. A lot of pride.”

In the days after the tragedy, Salas said, he and his friends wanted to take revenge, and even spoke of forming vigilante squads. But gradually, his group, Tierra, which started out as a largely apolitical night-club band playing covers of Motown hits, found that it could express deeper sentiments though its music.

“We realized that we can say something and make a difference,” Salas said. “Before nobody was listening.”

The moratorium instilled a sense of creative mission in other young Chicano artists, said Herron, who besides playing for Los Illegals was a member of ASCO, the influential Chicano artists collective that also included Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk and Patssi Valdez.

“The moratorium just made us blossom,” Herron said, comparing the Chicano arts movement to the great muralist projects of post-revolutionary Mexico. “It was like, this is my purpose for my art now: the police riots, the [student] walk-outs that had happened in the late ‘60s.”

In some ways, Saturday’s activities will underscore how much has changed since 1970 in East Los Angeles, an unincorporated area whose population is more than 95% Latino. The concert will take place at a bucolic amphitheater on the edge of Belvedere Lake, abutting the East Los Angeles Civic Center, a park-like complex of municipal government buildings, fountains and a bilingual library, near a new Metro Gold Line station. Saturday’s activities will overlap with the East L.A. Chamber of Commerce-sponsored third annual Taste of East L.A. food festival.

Angie Castro, press deputy for L.A. County Supervisor Gloria Molina, whose First District includes the area, said that eventful summer 40 years ago forged many important links within the community. “Everybody’s connected somehow, and it all goes back to those times when people were fighting for equality and access and services,” Castro said.

Other cultural events this summer are reconsidering the effect of that fateful day. An exhibition at the Mexican Cultural Institute next to Olvera Street displayed photos and graphic images of the era. At Corazón del Pueblo in Boyle Heights, Teatro Urbano is presenting a play, “The Silver Dollar,” written and directed by Rene Rodriguez, through Sept. 11, including a memorial performance at 5 p.m. Sunday. Both implicitly and explicitly, some events are raising parallels with the current heated immigration debate.

Saturday’s concert will include both acoustic and electric sets, with the various musicians uniting for a monster-jam finale. Herron said the set list will include original songs as well as “reinterpreted” covers of tunes such as Foo Fighters’ “My Hero.”

If they do their job right, Velo suggested, he and his colleagues might help inspire a new generation of artists in Saturday’s audience.

Spurring people into action, Velo said, “is just as good as getting encores.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.