Charles Manson follower Susan Atkins dies at 61

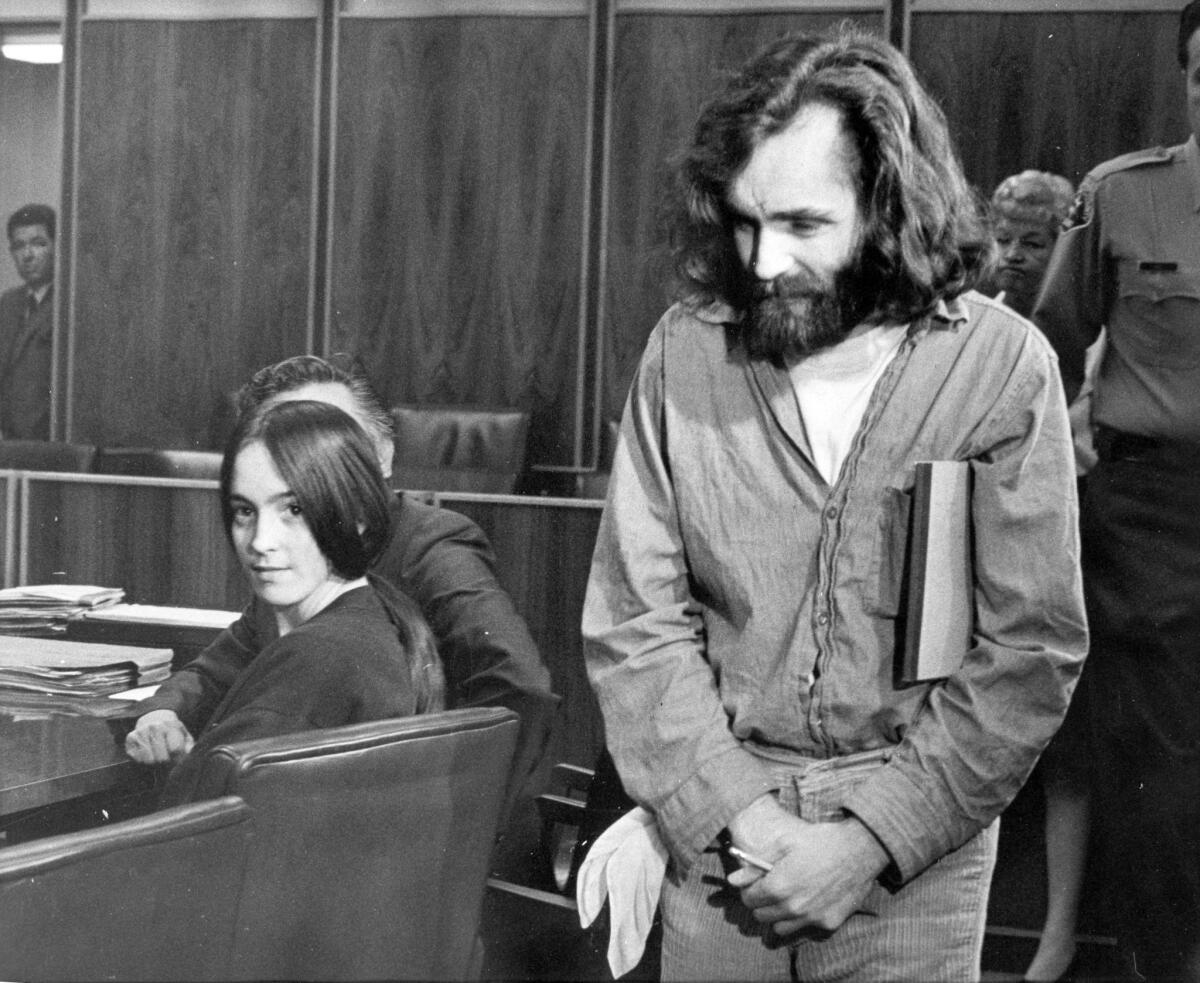

Susan Atkins, who committed one of modern history’s most notorious crimes when she joined Charles Manson and his gang for a string of killings in 1969 that terrorized Los Angeles and put her in prison for the rest of her life, has died. She was 61.

Atkins was diagnosed in 2008 with brain cancer and was receiving medical treatment at the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, where she died at 11:46 p.m. Thursday, said Terry Thornton, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Thornton attributed the death to natural causes, but an official cause of death will be determined by the Madera County coroner’s office after a review of Atkins’ medical history.

Convicted of eight murders, Atkins served more than 38 years of a life sentence at the California Institution for Women in Chino. She was the longest-serving prisoner among women currently held in the state’s penitentiaries, Thornton said. That distinction now falls to Patricia Krenwinkel, who was convicted along with Atkins in the Tate-LaBianca murders

Although prison staffers and clergy workers commended Atkins’ behavior during her many years behind bars, she was repeatedly denied parole, with officials citing the cruel and callous nature of her crimes.

In June 2008, she appealed to prison and parole officials for compassionate release, but the state parole board denied the request. On Sept. 2, she was wheeled into her last parole hearing on a hospital gurney, but was turned down by a unanimous vote of the 12-member California Board of Parole.

Atkins confessed to killing actress Sharon Tate -- the pregnant wife of director Roman Polanski -- who was stabbed 16 times and hanged; Tate’s nearly full-term fetus died with her. The next night, Atkins accompanied Manson and his followers when they broke into the Los Feliz home of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca and killed them.

“She was the scariest of the Manson girls,” said Stephen Kay, a former Los Angeles County deputy district attorney who helped prosecute the case and argued against Atkins’ release at her parole hearings. “She was very violent.”

Former chief prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, who sought and won death sentences for Atkins, Manson and other followers, said Atkins would be remembered “obviously as a member of a group that committed among the most horrendous crimes in American history. She apparently made every effort to rehabilitate herself.”

He added: “It has to be said that she did pay substantially, though not completely, for her incredibly brutal crimes. And to her credit, she did renounce -- and, I believe, sincerely -- Charles Manson.”

It was Atkins who broke open the case when she bragged of her participation in the slayings to cellmates at Sybil Brand Institute in East Los Angeles, where she was being held on other charges; two of her cellmates told authorities of her confession.

Atkins subsequently appeared before a grand jury, providing information that led to her own indictment, as well as that of Manson and others. Later, in a lurid, 10-month trial, she provided crucial testimony that fed the public’s fascination with Hollywood celebrities, drugs, sex and violence.

It also left an unshakable image of Atkins as a remorseless killer, who taunted the court at her sentencing with chilling words: “You’d best lock your doors,” she said, “and watch your own kids.”

In 1971, two separate juries found Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel and Charles “Tex” Watson guilty on seven counts of first-degree murder. Another Manson follower, Leslie Van Houten, was convicted of two murders.

All received the death sentence, later reduced to life terms after the California Supreme Court abolished the death penalty in 1972. (The Legislature later reenacted the death penalty statute.) Manson, Krenwinkel, Watson and Van Houten remain in prison.

Atkins also pleaded guilty to the murder of musician Gary Alan Hinman, who was killed in a dispute over money shortly before the Tate-LaBianca murders. She received another life sentence for the Hinman killing.

In prison, Atkins embraced Christianity and apologized for her role in the crimes. Prison staff endorsed her release at a hearing in 2005, but she was denied parole for the 13th time.

Born Susan Denise Atkins in San Gabriel on May 7, 1948, she grew up in San Jose, the middle child of three. When she was 15, her mother died of cancer. Her father sold the family home and all their furnishings to pay the hospital bills. Atkins began failing school and her father became an alcoholic who frequently left Susan and her younger brother, Steven, to fend for themselves.

Her father eventually abandoned them for good. Susan and her brother moved to the rural Cental Valley town of Los Banos, where their grandparents lived. Susan enrolled in high school and got a job as a waitress but was overwhelmed by the stress of trying to care for her brother, work and go to class. At one point, she and Steven were in foster care. Susan dropped out of school in the 11th grade and started drifting. Years later, she would describe her frame of mind during this period as “extremely angry, extremely vulnerable and directionless.”

Of all the Manson family killers, except for Manson, Atkins “had the most unfortunate background,” Bugliosi said.

The petite, dark-haired teenager hitchhiked to Washington, then Oregon, where she accepted a ride in a stolen car and was arrested on charges of car theft and concealing stolen property. She was released on probation and moved to San Francisco, where she worked briefly as a topless dancer in a North Beach bar.

In 1967 in Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco’s haven for hippies and other wanderers, she met Manson, an aspiring songwriter with an affinity for hallucinogenic drugs and free sex. He called himself and his followers “Slippies,” who posed as peace-loving hippies while planning a hair-raising assault on society.

According to Bugliosi in “Helter Skelter,” his bestselling 1974 book on the case, Atkins was instantly drawn to Manson, who seduced girls by playing on their insecurities. She testified under questioning by Bugliosi that before she met Manson she had felt she was “lacking something,” but then “I gave myself to him, and in return for that he gave me back to myself. He gave me the faith in myself to be able to know that I am a woman.”

Manson also gave her a new name, partly to make a joke on the establishment he loathed but also to cut her off from her past. “Tell them your name is Sadie Glutz,” he told Atkins. As in all other matters, she followed his command.

By August 1969, the Manson family’s base of operations was Spahn Ranch, a 500-acre property in the Santa Susana Mountains above Chatsworth where many old westerns were filmed. They took drugs, had group sex, stole credit cards and scrounged trash bins for food.

They also practiced what Manson called “creepy crawling,” which involved randomly picking a house somewhere in Los Angeles and entering it while the occupants were asleep. Bugliosi called these expeditions “dress rehearsals for murder.”

On the night of Aug. 8, Manson instructed Atkins and other followers -- Krenwinkel, Watson and Linda Kasabian -- to don their dark clothes and pack knives. Manson stayed at the ranch while they drove through the Hollywood Hills, winding up at the Tate residence in Benedict Canyon.

Around midnight, the nightmare began.

The first to die was Steven Parent, 18, a friend of Tate’s caretaker, who encountered the murderers as he was leaving the estate. The other victims were inside the main house: Tate, 26, best known for her role in the movie “Valley of the Dolls”; Hollywood hairstylist Jay Sebring, 35; Voytek Frykowski, 32, a friend of Polanski, who was out of the country; and Abigail Folger, 25, a coffee heiress and Frykowksi’s girlfriend.

Atkins later admitted stabbing Frykowski and Tate. She said that before fleeing the scene, Watson ordered her to leave a message in the house that would “shock the world,” so she used Tate’s blood to write “PIG” on the front door.

At her parole board hearing in 1993, an official asked Atkins if Tate said anything to her in her last moments.

“She asked me to let the baby live,” Atkins said tearfully. “I told her I didn’t have mercy for her.”

The night after the Tate killings, Manson led a group that included Atkins, Watson, Krenwinkel and Kasabian on another expedition. They wound up at the LaBianca home. Manson tied up Leno, 44, and Rosemary, 38, then left the killing to Watson, Krenwinkel and Van Houten. Afterward, they took a shower and made a snack in the LaBiancas’ kitchen before departing. Atkins stayed in the car.

The ‘60s “abruptly ended on August 9, 1969,” Joan Didion wrote of the shocking crimes that closed a decade pocked with assassinations, Vietnam War deaths and other violence. The Tate-LaBianca murders made some people fear “that they had somehow done it to themselves,” Didion said, “that it had to do with too much sex, drugs and rock and roll.”

Atkins married twice while in prison. In 1981, she married Donald Laisure, a self-proclaimed Texas millionaire who had been married 35 times before. The marriage ended when Laisure said he planned to take his 37th wife.

In 1987, she married James W. Whitehouse, an Orange County attorney who represented her at her last few parole hearings. He survives her along with a son she gave up when she went to prison.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.