Reshined ‘Shoes’

Few films have more passionate partisans than Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s “The Red Shoes,” but no matter how much you love it, you probably don’t know it as intimately as Robert Gitt.

Gitt spent so much time looking at the 1948 British classic he not only can tell you how many frames it contains -- 192,960 in the print, 578,880 in the tripartite negative -- but what had gone wrong with each and every one of them, from a massive attack of mold to wonky negative shrinkage.

Gitt knows all this because as preservation officer at the UCLA Film & Television Archive, he’s spent the last 2 1/2 years supervising a painstaking restoration of this landmark three-strip Technicolor film. He watched it so long and so hard he can recite the dialogue, and Barbara Whitehead, the assistant film preservationist who worked with him, knows the ballet choreography by heart.

All this demanding effort -- Gitt called it one of the most complicated endeavors of his career -- paid off Friday night when the “Red Shoes” restoration was scheduled to have its world premiere on the big screen at the Cannes Film Festival’s glamorous Salle Debussy. (Time and place for an eventual Los Angeles screening have yet to be determined.)

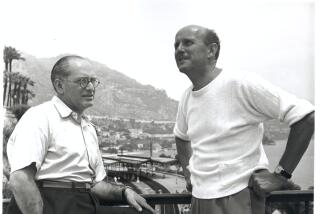

The film was to be presented by two of its most illustrious devotees, director Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker, Scorsese’s longtime editor and Powell’s widow. Scorsese and Schoonmaker consulted closely with Gitt and Warner Bros. Motion Picture Imaging, which did the digital picture restoration, with Schoonmaker providing meticulous notes that proved invaluable.

--

A Scorsese favorite

Though the Hollywood Foreign Press Assn. donated the lion’s share of the funding, it was the Film Foundation, the preservation organization headed by Scorsese, which decided to restore the film and selected UCLA for the job.

“It’s one of Scorsese’s favorite films of all time; he saw it when he was a little boy and it had a great impact,” UCLA’s Gitt says. The director once wrote that the film’s “swirl of color and light and sound all burned into my mind from that very first viewing, the first of many.”

When Powell and Pressburger (who took the unusual joint “written, produced and directed by” credit) began work on “The Red Shoes” in 1946, after the success of their stunning “Black Narcissus,” they now “had the world at their feet,” Powell recalled in his lively autobiography “A Life in Movies.” Still, their bankers “must have paled and looked at each other with a wild surmise” when they announced that their next project was to be a film about ballet.

--

Lengthy ballet sequence

And not just any film about ballet. Powell told Pressburger, “I’ll do it if a dancer plays the part and if we re-create an original ballet of ‘The Red Shoes’ instead of talking about it.” Which was exactly what happened when Moira Shearer, a rival of Margot Fonteyn’s at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, took the role and the “Red Shoes” team created a 17-minute ballet sequence, unheard of at the time -- “such a ballet,” Powell promised, “as audiences have never seen.” It was choreographed by Robert Helpmann.

The “Red Shoes” plot was loosely inspired by a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale of a girl who wants a pair of red shoes to dance in but is horrified to discover that though she gets weary, the enchanted shoes never tire and end up dancing her to death. Similarly, in the film, ballerina Victoria Page has to make the impossible choice between devoting her life to dance or to love.

So skeptical of success were the film’s backers they forced Powell and Pressburger to sacrifice part of their cash advance for a bigger portion of the film’s receipts. As Powell wrote, “twenty years later, when ‘The Red Shoes’ was one of the top-grossing box-office films of all time and was included in Variety’s ‘Golden Fifty’, we were glad to have made the sacrifice.”

The huge success of “The Red Shoes,” including five Oscar nominations and a two-year run in New York, came from a pair of factors. One was its position, unusual for the time, as a work of art that passionately celebrated creativity and the artistic impulse. As Powell wrote, “We had all been told for ten years to go out and die for freedom and democracy, for this and for that, and now that the war was over, ‘The Red Shoes’ told us to go and die for art.”

The other major factor was the gorgeous color photography of Jack Cardiff. The UCLA restoration does full justice to what has to be one of the most exquisite color films ever made, filled with the kind of deep, vivid hues that will leave viewers literally gasping.

Not that restoring those colors to their original brilliance was easy. First, it turned out that every reel of the original negative, which had been stored in Great Britain, had been attacked by mold, causing what Gitt describes as “thousands of visible tiny cracks and fissures.”

To get rid of the mold, Whitehead had to both use ultrasonic cleaners and hand-clean parts of the negative frame by frame with perchloroethylene, commonly known as perc, a hazardous fluid usually used in dry cleaning.

Another problem discovered early on was that “there were thousands of visible red, blue and green specks caused by embedded dirt and scratches.” Once all this was dealt with, Gitt remembers, “we breathed a big sigh of relief, we thought we were free and clear.” It was then that yet another problem, negative shrinkage, was discovered.

--

A Technicolor issue

As its name indicates, three-strip Technicolor was shot with three different negatives, and over the course of time some of the negatives had shrunken to different sizes. Also, it turned out that the camera had been out of adjustment for much of the shoot, and the equipment Technicolor had originally used to adjust for that was no longer functional. As a result, the images looked like a 3-D movie without the glasses, with red and green fringes around the sides.

These problems, and others, including the “flickering, mottling and ‘breathing’ ” of the image, were all corrected via digital restoration to the point where “The Red Shoes” actually looks better now than it ever has. “In 1948, images were fuzzy by today’s standards,” Gitt explains. “And because there was more information on the negative than could be printed at the time, we got a lot more off it than they were able to do when the film first came out.”

Those red shoes have never looked redder, or more alluring, than they do today.

--

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.