Pee-wee’s back in the limelight

You are all lucky boys and girls, however old you are, because tonight “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” comes back to TV. As part of its Adult Swim franchise, the Cartoon Network will begin airing the show’s original 45 episodes, which ran over five seasons of Saturday mornings on CBS from 1986 to 1991. That it will run at 11 p.m. is not especially child-friendly, except in households with advanced bedtime rules, so fire up the TiVo or the VCR, you with small fry or your own early bedtimes. (The show has been available on DVD since November 2004, but that is not at all the same sort of cultural moment.)

A winner of multiple Emmy Awards, “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” is a pretend children’s show that became a real one, a fact that you can see as some kind of meta-event or just as a version of “Pinocchio.” It has some of the recombinant postmodern qualities but none of the jaded irony of its Adult Swim neighbors, many of which work by amplifying the creepy unintended subtexts of old cartoons.

But although some do find the “Playhouse” itself creepy -- and so rife with hidden meaning that they write articles with titles like “The Playhouse of the Signifier,” “Pee-wee Herman: The Homosexual Subtext” and “The Cabinet of Dr. Pee-wee: Consumerism and Sexual Terror” -- the show itself is a thing of pure celebration.

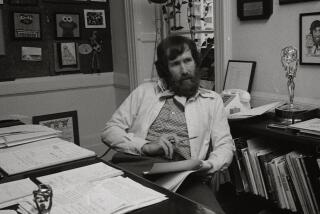

“I’ve been really careful to try to not dissect what I do, what I did, too much,” Paul Reubens said one afternoon in his publicist’s West Hollywood office.

The man who was and is Pee-wee is now 53 and a few pounds heavier but otherwise the off-duty image of his alter ego. He is soft-spoken where Pee-wee is explosive and self-deprecating where Pee-wee is ... not self-deprecating.

“There are college dissertations on ‘Pee-wee’s Playhouse,’ Miss Yvonne and her raincoat, and what does it all mean, and reading things in that I really didn’t feel like I meant or was trying to do,” he said. “People writing about the underlying whatever in both the ‘Playhouse’ and the movies, and some of it, I go, ‘Well, that’s not hidden, it’s all right out on the table.’ ”

Children’s TV was once alive with actual human beings, often accompanied by puppet friends and with a cartoon or two to present. In my own childhood, there were Engineer Bill, Sheriff John, Hobo Kelly, Tom Hatten (who dressed like a sailor and ran “Popeye” cartoons). These were “come and visit” shows, in which you entered the world of your hosts, who addressed you directly through the screen and might say your name on your birthday. This is the model of the Playhouse.

“ ‘Mickey Mouse Club,’ ‘Howdy Doody, ‘Captain Kangaroo’ -- I was obsessed with those shows,” said Reubens. “I can remember sitting on our living room floor watching the last episode of ‘Howdy Doody,’ when they were saying goodbye forever, and just bawling my head off and thinking, what kind of world is this? How could society be so screwed up as to let ‘Howdy Doody’ go off the air?”

Even the venerable “Captain Kangaroo,” which had been muscled into the weekend by the expanding morning news, was gone by the time “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” bowed. Cartoons were king then, and when CBS approached Reubens -- who had developed the character through a popular Groundlings stage show (“The Pee-wee Herman Show,” taped by HBO and coming out on DVD on July 18) and the 1985 film “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure” -- about the possibility of a “Pee-wee” cartoon, he pressed for live action. The show is nevertheless full of marvelous animated sequences, some by Peter Lord and Nick Park of Aardman Animation/”Wallace & Gromit” fame.

“I keep flashing on kids today watching shows on an iPod screen and starting off from before they can remember seeing computer-generated images on games and movies and cartoons,” Reubens noted. “And I can picture young people in the very, very close future looking at anything with real people in it and bursting out laughing, and going, ‘Oh, my God, this is before they figured out that real people didn’t have to do this.’ ”

As with most shows for the young, dependability reigns, notwithstanding the chaos and noise: At the Playhouse, there is always a “secret word” for the day, which is a cue for everyone to “scream real loud” -- words like “here,” “on” and “this” that guarantee a lot of screaming. We know that at some point, Jambi the Genie will grant a wish and instruct the wisher(s) -- and you at home -- to chant, “Mekka-lekka hi mekka hiney ho!,” and that the King of Cartoons will arrive at some point to say, “Let the cartoon begin,” but will first forget to say it.

Pee-wee himself is kind of a human optical illusion -- in his undersize gray suit, red bow tie, white socks and shoes and 1959 grade-school haircut, he’s simultaneously a man acting like a child and a child pretending to be an adult. It only doesn’t make sense if you look too hard. (In his two movies and original stage show, he is a little more of an immature adolescent.)

Elbows tucked in tight against his sides with forearms flailing, the top half of his body not always on the same mission as his bottom, he careens through his multicolored explosion-in-a-toy-factory world, coming up close to the camera to wink, smile or chuckle his trademark two-beat laugh. As impulsive as he can seem, he’s also the authority figure, the one who ultimately decides what games to play and what projects to take on and who answers questions or knows how to find answers to questions he doesn’t know.

The other human characters are spins on the generic figures that populated children’s TV and literature in Reubens’ own childhood: the cowboy, the sailor, the genie, the beautiful lady, the mailman, the cab driver, the king -- although here, the cowboy (Laurence Fishburne in jheri curls) is black, the cab driver is a woman, and the mailman is a black woman (S. Epatha Merkerson, later of “Law & Order”).

The show’s inclusiveness extends to the animal, mineral and vegetable kingdoms as well. There are talking fish; a pterodactyl; a beatnik trio of cat, dog and chick; plus the bovine Countess, a talking chair (named Chairry), a talking globe (named Globey), a talking floor (named ... Floory) and a talking beatbox-turntable-robot (named Conky, I don’t know why). As designed by Gary Panter, a punk-connected comic and poster artist whose work Reubens admired, the whole place is busy and alive, patterned, splattered, jagged, ragged and off-kilter, with the look of being hand-made.

Like the punk and new wave scenes that flourished around the time of Pee-wee’s ascension, the show speaks loudly to making the marginal the mainstream. Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh contributed to the music, Cyndi Lauper sang the theme. Reubens calls “Playhouse,” among other things, “a celebration of nonconformity, being energetic and doing what you want.” It could only have been made by outsiders.

It’s easy to view the show, in its progress from stage to screen to little screen, as something that was at first geared primarily to adults and morphed into something mainly for children -- with an accompanying increase in double-entendres, although Reubens believes “the stage show was a full-on real kids show. We actually did matinees of it at the Groundlings for kids.” At the same time, there is undeniably a puckishness there that exploits juvenile interest in body parts and functions. The farewell salutation “I’ve got to go, P.” is one running joke, and there are lines like “How’s your wiener, Cowboy Curtis?” (as in hot dog); in one episode, Pterri the Pterrodactyl takes a rather long look down Miss Yvonne’s deep cleavage. “The view’s good from here” says Pterri. (“I think there’s a little vulture in you,” replies Miss Yvonne.) This is perhaps strange but hardly dangerous.

“My theory has always been, and continues to be, if a kid laughs at a dirty joke, then they already know -- I didn’t teach it to them -- they have that vocabulary,” said Reubens. “And if they don’t, it’s designed to go over their heads. The highlight for me, of those years, was when we were in the writers room and someone would say something, and I could just see a 5-year-old falling off the couch, killing a 5-year-old with laughter.”

The budget for the show was unusually high, at least at first, and allowed for a lot of beautiful puppet and clay animation. The final season, which was completed but pulled after Reubens was famously arrested in a Sarasota, Fla., adult movie theater and charged with indecent exposure (a charge he denied but to which he pleaded no contest), seems to be made with perhaps a hint of exhaustion and an overreliance on filling time with old found footage.

Yet there are beautiful moments too, as when Pee-wee and Cowboy Curtis visit the Grand Canyon and lie back and watch the stars to contemplate the enormity and the beauty of the universe.

Although the character of Pee-wee Herman has not been seen in public since a Minnie Pearl tribute in 1992, Reubens shows up regularly in small films and as a voice artist; he also recently appeared (eminently recognizable behind glasses and a big fake mustache) in a video for the Raconteurs, White Stripe Jack White’s other band.

It is widely believed that Reubens’ 1991 arrest killed Pee-wee forever, but Reubens is not done with him. He has two Pee-wee scripts finished: One is a revised version of an unproduced screenplay he wrote with Panter, a “Playhouse” adventure featuring the usual suspects. The other is “dark,” a “Valley of the Dolls” story that seems from reports to obliquely refer to some of his own personal trials.

“I never said it was over or I didn’t want to do it anymore,” Reubens said about the possibility of putting on the suit and bow tie again. “That’s something that’s been said by other people.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.