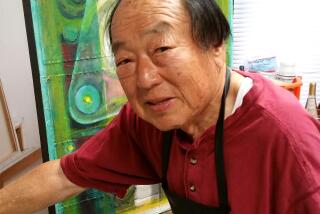

Kenzo Tange, 91; Architect Blended Traditional Japanese, Modern Elements

Kenzo Tange, whose reconciliation of traditional Japanese architecture with modernity shaped Japan’s rise from the ashes of World War II, died of heart failure at his Tokyo home Tuesday. He was 91.

Tange leaves his architectural fingerprint on the skylines of Jidda in Saudi Arabia, Skopje in Macedonia, and Singapore. But it is in Japan that he forged a reputation as the foremost architect of his generation, designing civic buildings -- including sports venues, auditoriums and city halls -- across the island nation during the burst of reconstruction in the 1950s and ‘60s.

His legacy includes the Hiroshima Peace Center memorial on the site of the atomic bombing, the twin gymnasiums that curl like commas built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and the uncharacteristically garish New Tokyo City Hall complex, commissioned amid Japan’s economic boom of the 1980s.

Critics attacked the upward-thrusting skyscraper as the “Tower of Bubble.”

Tokyo was Tange’s main canvas. The city had been razed by the firestorm of American bombings in the last months of World War II, and the aftermath created not just a desolate landscape, but the rare chance to imagine -- and design -- the look of the reborn metropolis.

The city bears the imprint of that imagination. Tange designed renovations to the bustling Tsukiji fish market -- the world’s largest. He designed embassies and office towers. His firm built the somewhat bizarre Fuji TV center.

Tange’s influence was extended by his prolific writings on architectural theory and by his role as a teacher at prestigious Tokyo University. Most of Japan’s significant postwar architects crossed paths with Tange, and his theories on controlling urban congestion and chaos spawned a futuristic school of design in the 1960s known as the Metabolists.

They waged a war for order in mega-cities, though some of those disciples later spun out of Tange’s orbit. They broke with his disciplined style and turned Japan’s cities into exuberant architectural playgrounds.

“His closest parallel is Philip Johnson; they were both pioneers and godfathers of architecture who were extremely influential on others,” Akira Asada, one of Japan’s foremost cultural critics, said in comparing Tange to one of America’s leading 20th century architects. “But Tange, even more than Johnson, was not just a propagandist for his ideas; he was a terrific architect, perfectly in tune with Japanese society after the war.

“His works at Hiroshima and the Olympics were national symbols of recovery, and they will be remembered as masterpieces,” Asada said.

Tange’s work impressed foreign observers as well. In 1987, he became the first Japanese architect to win the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s most prestigious award.

The jury declared his Olympic stadiums to be “among the most beautiful structures built in the 20th century.”

Tange was born in Osaka, but his banker father, Tatsuya, moved the family to China, landing in the British quarter of Shanghai when Tange was an infant.

“One of my oldest memories is from my time in Shanghai, and it is related to architecture,” Tange wrote in a 1983 newspaper column called “My Resume.” He described the family’s four-story home as something one would see in London, with its red bricks, garden and servants rooms.

But his parents also furnished the third floor with Japanese tatami mats, offering the young Tange an early awareness of the possibilities for fusing Eastern and Western design.

The family returned to Japan in 1920, settling into a traditional thatched-roof Japanese house in the port town of Imabari on Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands.

Tange left that quiet backwater for the capital during the turbulent 1930s, graduating from Tokyo University’s architecture department in 1938.

He then joined the architectural firm of Kunio Maekawa, who had worked in the Paris office of Swiss modernist Le Corbusier.

The experience exposed Tange to Western influences during a fevered nationalist and militarist period in Japan, when official architectural policy was firmly focused on Asia.

Tange returned to Tokyo University for graduate studies in design from 1942 to 1945. With the war over, his fluency in the modernism that had been suppressed during wartime was suddenly in demand.

His breakout project came in 1949, when he won the competition to build a memorial for the Peace Park on the scorched landscape of ground zero in Hiroshima.

Tange’s concrete cenotaph is an arch that opens onto the public square that can accommodate up to 50,000 people. But he also blended some traditional Japanese elements into the memorial’s concrete form, despite widespread reluctance at the time to see any sign of the nationalist indulgences that had contributed to war and calamity.

“It was built in the empty devastation, and people first criticized that it looked like a big bird cage,” said Minoru Hatabuchi, the current director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. “Tange’s later works are great. But the Hiroshima museum shows his real soul and spirit.”

The memorial was finished in 1955, establishing Tange as the unrivaled dean of Japan’s architectural world. In 1959, he published his doctoral thesis on “Spatial Structure in a Large City” and, within a year, some of his followers drafted a manifesto called “Plan for Tokyo” that launched the Metabolist school of urban design.

The group advocated linking buildings and commuter routes with endlessly replaceable parts, and argued over the next decade or so for accommodating Tokyo’s pulsing growth by building on landfill over Tokyo Bay.

Meanwhile, Tange kept building. Some critics say he peaked creatively with his designs for the 1964 Olympics, which served as Tokyo’s symbolic reentry into the global community.

The graceful stadiums are still used for sports events.

Politically well-connected in a country where awarding public projects was frequently a clubby exercise, Tange became the go-to architect for many major Japanese projects. He was the main designer for the 1970 Osaka Expo.

By then he was also designing extensively abroad. He designed the Minneapolis Arts Complex (his only completed American work), royal palaces in Saudi Arabia and a chunk of Singapore’s rising skyline.

“He had good instincts and knew what’s good and what’s bad,” said Hiromichi Nakamura, who worked for Tange from 1971 to 1987. “He did not mix up his personal taste into projects, but always made good global judgment.”

Yet some contend that Tange allowed his personal discipline to slip near the end of his career amid the frivolity of the postmodernist free-for-all. If one project tarnished his career for critics, it was the New Tokyo City Hall, the mammoth twin towers with twisted tops and communications dishes on the roof that dominate the Shinjuku district.

The project aroused ire from the moment the commission was awarded to Tange in 1986.

Some raised questions about the fairness of the competition and Tange’s close ties to Tokyo’s top politicians. There was also dismay in some quarters about Tange’s design itself, which embraced the postmodernism he had so long disdained.

“If Tange had died after the Olympics, he would be remembered as a giant,” said Asada, the cultural critic. “Instead, he went on and did some ambiguous things. He may have been too willing at the end to get in sync with the fashionable postmodernist mode.

“But Tange never stopped wanting to build. He kept designing. And that’s something you have to admire.”

He is survived by his second wife, Takako, and a son, Noritaka Paul.

He will be buried Friday in a private ceremony in Tokyo’s St. Mary’s Cathedral, one of his landmark 1960s modernist creations.

Hisako Ueno of the Times’ Tokyo Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.