Family Man Arrested in 10 Slayings

WICHITA, Kan. — He called himself a monster, but in 31 years of hunting the serial killer known as BTK, Wichita police made it clear they were searching for a man who appeared in every way ordinary. On Saturday, they announced they finally had caught him.

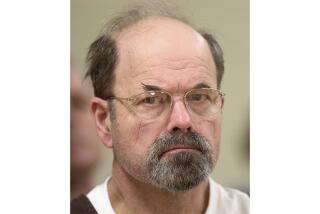

Dennis Rader, 59, a church-going family man, a Cub Scout leader, a dog-catcher for the trim suburb of Park City, is in custody on suspicion of torturing and killing seven women, one man and two children from 1974 to 1991 -- including two victims linked only this week to BTK.

Authorities would not discuss the specifics of their investigation into BTK. (The “code word” the killer used to describe himself described his method: bind, torture, kill). But they have compared Rader’s DNA with the semen that BTK left at several crime scenes.

They said they were confident that Rader was the man who terrorized this industrial city for decades, taunting detectives with poems, word puzzles and boastful letters -- including one in which he declared that there was “no help, no cure” for his sadism, “except death or being caught and put away.”

“Bottom line: BTK is arrested,” Wichita Police Chief Norman Williams said at a news conference Saturday morning. “Doggone it, we did it.”

Williams was hailed with a standing ovation. Some members of the victims’ families slumped in their chairs, sobbing.

“I can’t think,” said Dale Fox, the father of Nancy Fox, who was strangled in December 1977. “I’ve waited so long to hear the words, ‘We have him.’ ”

Rader’s name had surfaced on a list of possible suspects in the late 1970s when investigators cast a broad net, pulling up names of all white male students who attended Wichita State University at that time, said retired Det. Arlyn Smith, who worked on the case at the time.

Authorities suspected the killer might have connections to the university because one of his letters was reproduced on a copy machine students used -- and one of his poems appeared to be modeled after a verse in an obscure textbook from a folklore class. But Rader did not draw any particular scrutiny, Smith said. There were too many white male students to investigate them all, so detectives focused on those who gave them reasons to be suspicious.

“To the best of my recollection, [Rader] never matched any other list, so he was never specifically looked at,” Smith said.

Rader graduated in the spring of 1979, with a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice.

Rader’s name apparently surfaced again in recent months as detectives studied surveillance videos from businesses located near the spots where BTK dropped some of his mocking communications.

“They kept seeing this Park City animal control officer’s van,” said Robert Beattie, a local author who is writing a book about the case and who has extensive contacts with investigators.

Rader, who is married with two grown children, works as the animal control officer in Park City, a working-class suburb of ranch homes and fast-food restaurants about 10 minutes north of downtown Wichita. Part of his job was citing residents for violating municipal codes.

Although some of his neighbors said he was friendly -- and he was well-respected enough to serve as president of his church council -- others called him mean and arrogant. “He wore a badge and would swagger around the street like he was above the law. I always considered him a bully,” said James Reno, 42, who has lived across the street from Rader for more than a decade.

Maricela Cano, 23, who lived around the block from him for more than two years, said: “I can’t tell you how many times he made me cry. If he was outside, I would stay indoors and hide.” She said Rader constantly harassed her about her dogs, until she and her family moved across town.

On Saturday morning, her 5-year-old son was watching TV coverage of BTK when a picture of Rader flashed on the screen.

“He turned around and said, ‘Mommy, look. It’s the man who took away our dog,’ ” Cano said. “It freaked me out.”

Rader was so rigid about code enforcement, neighbors said, that he carried around a ruler to measure the height of grass on lawns he thought looked unruly.

Investigators noted that BTK was meticulous: When he broke a window to get into a victim’s house, he swept up the glass. In a few of his letters, he made a point of commenting on how tidy -- or dirty -- he found the victims’ homes and cars.

Rader was arrested as he was driving through Park City just before noon Friday. Later in the day, police seized computer equipment and numerous plastic containers from his single-story home. A mobile police laboratory was still parked in front of the house late Saturday.

Authorities would not say whether Rader has talked to them.

BTK, however, has been talking loudly, if cryptically, for decades.

His first known crimes were the murders of Joseph and Julie Otero and two of their children in January 1974. His method would become chillingly familiar to police: He cut the Oteros’ phone line, then apparently managed to get himself invited inside the house, where he bound, gagged and strangled his victims.

BTK claimed credit for the murders in a letter describing the crime scene in detail, including the color of the victims’ clothes. Though the victims were not sexually assaulted, he derived sexual pleasure from his attacks; he left semen at several of his crime scenes.

In the Otero letter, BTK warned he would kill again: “It hard to control myself,” he wrote, in the error-ridden prose that would be another of his trademarks. Over the next three years, he killed at least three more women.

He reached out to police several times, once calling 911 to direct authorities to his most recent victim. Then he went silent for a quarter century. In March, he resurfaced with a new letter, this one claiming credit for an unsolved 1986 strangling.

At the time, authorities speculated that newspaper coverage of the 30th anniversary of the Otero murders had prompted BTK to seek public acknowledgment of his other killings. In the last several months, BTK has reached out repeatedly, sending a word-search puzzle to a local TV station, writing a letter to police and leaving packages crammed with all manner of clues in public spots around town. BTK marked many of his letters with a secret code; the FBI was able to authenticate several of the recent communications.

In one, he included an outline for his autobiography. It ended with Chapter 13: “Will There Be More?” Another package contained a driver’s license that had belonged to one of his victims. A Post Toasties box left by the roadside last month -- a “B” and a “K” scrawled above and below the “T” -- contained jewelry that authorities said might have belonged to other victims.

(BTK’s habit of collecting souvenirs from his victims led some investigators to suspect he was single because they thought he would be unlikely to keep macabre trophies in a home where a wife or children could stumble across them.)

The flurry of recent communications from BTK captivated armchair detectives who noodled over every aspect of the case in Internet chat rooms. (Police paid close enough attention to the chatter that they subpoenaed information about several frequent contributors.) But even as the clues fascinated, they also frustrated, leaving many here wondering why police could not nab a killer who was dropping hints so brazenly. It seemed almost as though he wanted to be caught.

“It appeared he was leaving a trail, almost playing a game with detectives: See if you’re smart enough to find me,” said retired Wichita Police Capt. Bernie Drowatzky.

Authorities responded with an all-out push: They took DNA samples from at least 4,000 men, brought in the FBI, investigated thousands of leads called into a hotline.

On Saturday, they said their patience had paid off.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to see a light at the end of this very, very, very long tunnel,” said Wichita Police Lt. Ken Landwehr, who has been on the case since the Otero killings.

Authorities expect to hand their evidence to Sedgwick County Dist. Atty. Nola Foulston within the next few days.

If convicted, Rader would not face the death penalty because all the killings linked to him took place before Kansas introduced capital punishment in 1994.

Officials said they expected him to be charged with the eight homicides previously attributed to BTK. They said they had also linked him to two additional murders: the strangulations of Marine N. Hedge, 53, in April 1985 and of Delores E. Davis, 62, in February 1991. Hedge lived a few doors down from Rader.

Until recently, investigators had not connected the Davis and Hedge murders to BTK, in large part because both victims’ bodies were found some distance from their homes. BTK’s other known victims were all killed in their homes.

Rader’s arrest has raised the hope that detectives might be able to pin other unsolved murders on BTK.

At the very least, investigators who have studied the case for decades said they hoped they would come to understand a bit more about the serial killer who so baffled and frightened them.

They all have questions they’d like to ask: How did he pick his victims? Why did he claim credit for some murders and not for others? Why did he start communicating with police again after 25 years of silence?

One question that they do not need to ask is how he eluded capture for so long.

“We always said he was invisible because he was most likely so ordinary,” said Smith, the retired detective. “As it turned out, he was exactly ordinary. He went to work. He went to church. He went to Boy Scouts. He did family things. Just an ordinary guy.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Bind, torture, kill: a serial killer who taunted police

Dennis Rader is suspected of killing seven women, one man and two children from 1974 to 1991:

Jan. 15, 1974: Joseph Otero, 38, and his wife, Julie, 34, are strangled in their home along with two of their children, Josephine, 11, and Joseph, 9.

April 4, 1974: Kathryn Bright, 21, stabbed to death in her home.

October 1974: The Wichita Eagle-Beacon gets a letter taking responsibility for killing the Oteros; it includes crime scene details.

March 17, 1977: Shirley Vian, 24, tied up and strangled at her home.

Dec. 8, 1977: Nancy Fox, 25, tied up and strangled in her home. The killer’s voice is captured when he calls a dispatcher to report his own crime.

Jan. 31, 1978: A poem referring to Vian’s killing is sent to the Wichita Eagle-Beacon.

Feb. 10, 1978: A letter from BTK is sent to KAKE-TV claiming responsibility for the deaths of Vian and Fox, as well as another unnamed victim. The Wichita police chief announces a serial killer is at large and has threatened to strike again.

April 28, 1979: BTK waits inside a home but leaves before the 63-year-old female resident returns. He later sends her a letter letting her know he was there.

Aug. 15, 1979: Police get tips when TV and radio stations broadcast the voice of the BTK strangler from the 1977 recording.

April 1985: Marine N. Hedge, 53, strangled.

Sept. 16, 1986: Vicki Wegerle, 28, strangled in her home.

February 1991: Delores E. Davis, 62, strangled.

March 19, 2004: A letter arrives at the Wichita Eagle containing a photocopy of Wegerle’s driver’s license and photos of her body. Police link the letter to BTK.

Feb. 26, 2005: After receiving several more letters, authorities announce the arrest of BTK.

Source: Associated Press

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.