Maybe Anyone Can Be President

WASHINGTON — Blame Austria.

In 1772, Austria joined Prussia and Russia in dividing up Poland, which had been weakened by the election of a foreign-born head of state.

Fifteen years later, America’s Founding Fathers, leery of repeating Poland’s experience, added the following to their new Constitution: “No person except a natural born citizen ... shall be eligible to the Office of President.”

Today, a national -- if fledgling -- campaign is underway to allow foreign-born citizens to hold the nation’s highest office. Supporters expect congressional hearings on the proposal this year.

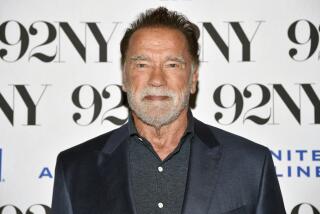

Long considered quixotic and un-serious, the effort is taking on interest-group support, money and organization. And although Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger has publicly asked to be left out of the debate, it is the political ascent of the governor, who holds both Austrian and American citizenship, that is attracting attention to the issue.

Among backers of various proposed constitutional amendments are members of both political parties and some of America’s most liberal and conservative legislators. Both the incoming and outgoing chairmen of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, which considers constitutional amendments, support the change.

“This restriction has become an anachronism that is decidedly un-American,” Sen. Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah), the past chairman, said recently.

Sen. Arlen Specter (R-Pa.), who succeeded Hatch, said of Schwarzenegger: “The guy has become governor of California. What more credentials could you ask?”

Some senators are less enthusiastic. The ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Patrick Leahy of Vermont, has denounced the legislative attention to the issue, saying the Senate had more pressing matters.

Just 27 of more than 10,000 amendments proposed have succeeded. To amend the Constitution, a proposal needs the support of two-thirds of both houses of Congress, followed by ratification by 38 states. The Constitution also can be amended when two-thirds of state legislatures call for a constitutional convention (which has never occurred).

Only on rare occasions when there is consensus does this happen quickly: The 26th Amendment lowering the voting age to 18 was ratified in four months in 1971.

Polls show that most Americans oppose amending the “natural born clause,” though a Gallup Poll released recently showed that opposition fell -- from 67% to 58% -- when Schwarzenegger’s name was mentioned to those surveyed. A Field Poll last fall found that even in California, where Schwarzenegger’s approval ratings then approached 70%, nearly 60% of registered voters surveyed opposed a constitutional amendment.

Nonetheless, support for the idea has started to build. Immigrants’ rights organizations, veterans groups and people who have adopted children from other nations have begun to speak out on the need to change the Constitution.

Three organizations have been formed to advocate for an amendment. Meetings to plan a campaign for the measure are scheduled for this month in Pasadena, Indian Wells, San Diego and Santa Barbara, and in Florida in March.

Amendment advocates offer many arguments. Children born overseas and adopted by American families, they say, know no other country; why should they not be able to lead it?

Statistics are often cited in their arguments. With the U.S. doubling its number of naturalized citizens -- from 6.5 million in 1990 to more than 12 million today -- ineligible citizens make up a growing percentage of the population. Many foreign-born people have risked their lives or died for the country (700 have earned the Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. military decoration.).

And if American-born convicts or terrorists are constitutionally eligible, why not Schwarzenegger or Jennifer Granholm, the Canadian-born Democratic governor of Michigan?

It is Schwarzenegger’s case, though, that has added stardust to the emerging coalition in favor of an amendment.

A contingent of chiropractors, some of whom meet each year during Schwarzenegger’s annual fitness expo in Ohio, is speaking out in favor. A political consultant for the governor is monitoring the issue on his behalf. A Silicon Valley donor to his campaigns has started a website, www.amendforarnold.com, and made two TV ads in favor of the amendment, and in January opened a full-time office on a Menlo Park thoroughfare for her organization, Amendus.org.

“He’s done everything but send us smoke signals,” says that donor, Lissa Morgenthaler-Jones, who boasts of volunteers in all 50 states.

Although the governor has been coy about his ambitions, his interest in the presidency is neither new nor a secret.

In an outtake from the 1970s documentary “Pumping Iron,” Schwarzenegger -- not yet a U.S. citizen -- is asked at a bodybuilding tournament when he will run for president. Schwarzenegger’s firm answer: “When [Richard] Nixon gets impeached.”

Moreover, Schwarzenegger as a potential president is a notion with a long history. In a 1991 satirical novel, “The Americans Are Coming!” Schwarzenegger defeats game show host Pat Sajak in a 1996 presidential election, overcoming “the old steroid stories and the Hitler stuff.”

“It was meant to be a laugh,” says author Alex Beam, now a columnist for the Boston Globe.

Two years after the novel, the notion of a Schwarzenegger presidency was dropped into a Sylvester Stallone sci-fi movie, “Demolition Man.” In the movie, Stallone’s character is frozen and awakened in 2032, when he is shocked to learn from co-star Sandra Bullock that Schwarzenegger has been president.

All that may still seem outlandish to Americans, but there is at least one place where a significant number of people anticipate a Schwarzenegger White House. A poll last year found that 37% of Austrians believe the governor of California will become president of the United States one day.

*

The term “natural born” entered American history in a July 25, 1787, letter from John Jay, who became the first chief justice of the United States, to George Washington, then serving as president of the constitutional convention in Philadelphia.

“Permit me to hint,” Jay wrote, “whether it would not be wise and seasonable to provide a strong check to the admission of foreigners into the administration of our national government; and to declare expressly that the Command in Chief of the American army shall not be given to, nor devolve on, any but a natural born citizen.”

Jay did not set out his reasons, but fears of foreign influence ran deep. Rumors abounded that the convention was planning a monarch and would invite the second son of George III to wear the crown. And there had been the partition of Poland.

Two days after Washington sent Jay a note of reply, the Constitution’s drafting committee revised its clause on presidential eligibility. “No person except a natural born citizen or a citizen of the U.S. at the time of the adoption of this Constitution shall be eligible.”

The provision kept out only future foreign-born citizens. The grandfather clause made every single framer of the Constitution -- seven of them foreign-born -- eligible for the presidency.

The debate over the clause began while the ink on the Constitution was still wet.

There have been at least 35 attempts to eliminate the clause, according to research by Washington lawyer Jim Ho in the law journal Green Bag.

Most of the proposed amendments have been introduced in the years immediately after wars. The clause came closest to demise in the years after the Civil War, when a surge of proposals produced the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments.

In 1871 and 1872, the matter reached a vote in Congress; each time, the amendment received a majority of those voting but fell short of the two-thirds required for passage.

The years after World War II saw 10 amendments proposed. The end of the Vietnam era sparked a similar boomlet, with eight amendments offered between 1971 and 1975.

The latest surge of interest dates to 1999, when media reports first suggested that Schwarzenegger was taking a serious look at his political career.

That year, Raimundo Delgado, an immigrant from the Azores and a schoolteacher in New Bedford, Mass., wrote a two-page letter to his congressman, Democrat Barney Frank, suggesting that the clause be eliminated.

Frank liked Delgado’s idea. The congressman introduced an amendment and, in July 2000, a House subcommittee held a little-noticed hearing on it.

Hatch, who has known Schwarzenegger for at least a decade, introduced the Equal Opportunity to Govern Amendment in July 2003. It would allow people who have been citizens for 20 years to serve as president. Schwarzenegger was naturalized in September 1983.

In October 2003, four days before California’s recall election that made Schwarzenegger governor, the Utah senator said in a speech in Washington that he could see Schwarzenegger as president.

“If he turns out to be a tremendous leader and he proves to everybody in this country that he’s totally dedicated to this country as an American,” Hatch said, “we would be wrong not to give him that opportunity.”

Over the last two years, Hatch’s amendment in the Senate has been joined by three similar amendments in the House. U.S. Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.) sponsored an amendment with a similar 20-year citizenship requirement, saying that Granholm, the foreign-born governor of his state, “would make an outstanding candidate.”

On a different front, Rep. Vic Snyder (D-Ark.), one of a group of lawmakers who work on international adoption issues, introduced an amendment that would allow citizens of 35 years’ standing to be president. It drew a dozen co-sponsors. Snyder’s niece, who was adopted from South Korea as a baby, “is a teenager now, and she is very much aware that she’s not eligible to run for president,” he says.

Schwarzenegger’s California election immediately added to the amendment proposal’s profile. He endorsed the idea of changing the clause in a February 2004 appearance on “Meet the Press.”

In early October, Hatch held a full hearing of the Judiciary Committee to consider the amendment. Afterward, Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.), who has repeatedly fought various efforts to change the Constitution, endorsed amending the clause.

But Schwarzenegger’s high profile has also energized the opposition. A Texas radio host, who often inveighs against what he calls a worldwide globalist conspiracy, has formed a group called Americans Against Arnold, which opposes the amendment proposals.

Commentators and editorial pages have argued that the Constitution should not be changed unless absolutely necessary. California politicians, including Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein and Hungarian-born Rep. Tom Lantos (D-San Mateo), have weighed in against it.

“I think this amendment, if it receives two-thirds in Congress, will have a very hard time being adopted by three-quarters of the legislatures of the states,” Feinstein said in Congress last fall.

For his part, the amendment’s most famous potential beneficiary mentions the idea only in answer to questions -- or when he wants a laugh.

Last year, Schwarzenegger began a speech to a convention of travel agents this way: “Thank you very much for changing the Constitution of the United States of America, and I accept the nomination for president. Wait a minute, this is the wrong speech!”

Times staff writer Richard Simon in Washington contributed to this report.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Constitutional options

Only 27 out of more than 10,000 proposals have actually survived the amendment process to become part of the Constitution. So an attempt to amend the nation’s charter - and remove a key obstacle for a presidential bid by California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger - is a longshot at best.

Two methods for amendments:

2/3 majority votes

The U.S. House and Senate each approves the bill by a two-thirds majority.

Ratification is required by 38 states

Constitutional convention

Must be called by two-thirds of the legislatures of the states.

Yes: 38 states

**

History of change

Congressional passage, rather than a constitutional convention, has been used for all ratified amendments. Most of those were fairly rapidly approved by the states. The Constitution sets no time limit, but Congress can require ratification within seven years. The most recent change, the 27th Amendment, took 203 years.

*--* Passed by Ratification Amendment Congress achieved 1-10: Bill of Rights 1789 1791 11: Judicial Limits 1794 1795 12: Choosing Pres., V.P. 1803 1804 13: Slavery Abolished 1865 1865 14: Citizenship Rights 1866 1868 15: Race No Bar to Vote 1869 1870 16: Income Tax Authorized 1909 1913 17: Sen. Elected by Pop. Vote 1912 1913 18: Liquor Prohibited 1917 1919 19: Women’s Suffrage 1919 1920 20: Presidential, Cong. Terms 1932 1933 21: Liquor Prohibition Repealed 1933 1933 22: Presidential Term Limits 1947 1951 23: Presidential Vote for D.C. 1960 1961 24: Poll Taxes Barred 1962 1964 25: Pres. Disability/Succession 1965 1967 26: Voting Age Set to 18 Years 1971 1971 27: Congressional Pay Raises 1789 1992

*--*

**

Failed attempts

Six amendments, which were passed by Congress, have failed to make their way into the Constitution:

Proposed amendment: Original 1st Amend.

Subject: U.S. House composition

Proposed: 1789

Last ratification: 1791

States ratifying: 10

Status: Pending

*

Proposed amendment: Anti-Title

Subject: Citizens accepting nobility

Proposed: 1810

Last ratification: 1812

States ratifying: 12

Status: Pending

*

Proposed amendment: Slavery

Subject: Banning federal interference in state institutions

Proposed: 1861

Last ratification: 1862

States ratifying: 2

Status: Pending

*

Proposed amendment: Child Labor

Subject: Regulate labor by those younger than 18 years

Proposed: 1926

Last ratification: 1937

States ratifying: 28

Status: Pending

*

Proposed amendment: Equal Rights

Subject: Codify equality of sexes

Proposed: 1972

Last ratification: N/A

States ratifying: N/A

Status: Expired 1982

*

Proposed amendment: D.C. Voting

Subject: District representation in Congress

Proposed: 1978

Last ratification: N/A

States ratifying: N/A

Status: Expired 1985

*

Sources: www.usconstitution.net; Emory University School of Law Electronic Reference Desk. Graphics reporting by Tom Reinken

LORENA INIGUEZ Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.