All the Makings for a Riot

ARGENTEUIL, France — Mourad surveyed his cold concrete world.

The official name of the housing complex, a wind-swept corridor of towers crammed with 17,000 people, is the Valley of Silver. Its nickname: the Slab.

“It’s very simple,” Mourad said. “There is a border between here and Paris, between rich and poor. And you can never really cross it.”

Mourad, 25, and his friends had taken refuge from the chill in a vestibule of an aging high-rise. Outside on the weather-beaten esplanade, mothers hunched behind strollers. Boys chased a soccer ball, breath steaming, near abandoned, rusty-shuttered storefronts. A pudgy Islamic fundamentalist -- djellaba robe over tube socks and sneakers -- carried groceries with his black-shrouded wife, whose veil revealed only her eyes.

The young men watched the esplanade, an expanse of walkways and plazas above street level, dingy tunnels for traffic below. It has been their playground, marketplace, battlefield. As Mourad sees it, the battle lines were drawn long before riots this fall made the Slab a stage in a national drama.

“They wait for the kids to get violent before looking for solutions,” said Mourad, a short, lean man with expressive brown eyes. “It’s not a question of justifying it. But how else do you want them to make themselves heard?”

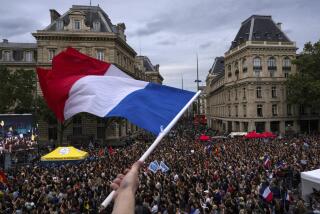

The riots began Oct. 27 about 15 miles east of Argenteuil after the accidental electrocution of two teenagers hiding from police in a power substation. A rampage of arson and violence spread from the industrial belt of Paris across the country, lasting three weeks and causing about $240 million in damage, France’s worst unrest in decades.

This city of about 100,000 suffered less devastation than other areas: about 30 burned cars, some vandalism, scattered brawls. But the Slab played a powerful symbolic role in a clash between youths and the state.

Two days before the rioting started, France’s tough-talking interior minister came to town, accompanied by a phalanx of police and journalists. The minister, Nicolas Sarkozy, arrived at 10:30 p.m., an hour when the Slab can get rowdy.

He was met by about 200 youths shouting insults and throwing debris. During the uproar, Sarkozy referred to young hoodlums with a word that means “rabble” or “thugs.” The incident became a rallying cry for rioters nationwide.

“It was like he prepared a theatrical piece by coming late at night, during Ramadan, with all those riot police,” said Mourad, who was on the esplanade, but denies throwing anything. “It was a provocation. That was why the kids responded that way.”

Two nights later, in a quieter but emblematic incident, Mayor Georges Mothron left a meeting at the Slab to discover that arsonists had torched his car. As he stared at the charred vehicle, 15 young men surrounded him. After a few edgy moments -- half-conversation, half-confrontation -- a community activist came to the mayor’s aid.

Mourad, the mayor and the activist experienced a microcosm of France’s urban crisis in markedly different ways. Seen through their eyes, the Slab sheds stereotype and hyperbole and turns out to be less hostile and more hopeful than its image.

Nonetheless, it struggles with a knot of problems requiring not just more jobs and cops, but also profound changes in how the French deal with one another.

*

The Angry Soldier

The vestibule echoed as two boys cavorted, thumping against a row of wooden mailboxes.

Mourad chided them quietly. He wore jeans and a black fatigue-style jacket zipped to his throat. He displayed a military ID card. A career in the army has steered him away from a gantlet of joblessness, drugs and prison. He has an apartment, a car, a girlfriend.

But modest success has only honed his resentment.

“I once gave this card to a policeman who stopped me to check my papers,” he said with a melancholy grin. “He laughed in my face. He thought it was some kind of joke. He took it to his supervisor, laughing. But when he came back, he was all pale. He saluted me. ‘Excuse me, I made a mistake.’ That kind of thing makes you angry.”

Mourad asked that his last name be withheld because of his profession. He is the French-born son of a Moroccan immigrant janitor.

“Our parents worked hard for France,” Mourad said. “We try to integrate. It’s society that doesn’t want to integrate us. They brought us here to this round place with these towers and they said this is the only option, the only perspective: You can live here all your life with all your cousins.”

Mourad’s criminal record consists of a juvenile arrest, but he describes a litany of run-ins with police. He says police treat the Slab like a colony and harass youths indiscriminately.

Especially if they venture into the lights of the capital.

“I once drove from Argenteuil to the Champs-Elysees, and the cops stopped me six times,” he said. “Six times! When I take the train downtown and they do patrols, I get up automatically” -- he spread his arms wide -- “so they can frisk me.”

The youths here see few faces like theirs in law enforcement, politics and business. Work has dried up at the factories that employed many of their parents.

“All they can imagine is working with their hands,” Mourad said. “A mechanic for guys, a cashier for girls. Or, let’s face it, selling drugs.... These guys can’t handle school. Most of their parents can’t even read and write.”

Mourad accosted a hulking African 15-year-old who strode into the vestibule: “Hey, Dari, what do you want to be?”

Dari scowled reflectively. “A criminal!” Howls from the homeboys. Dari continued: “School sucks. The teachers don’t like Africans and Arabs.”

Mourad thinks the Slab finally gave a voice to all that alienation in the incident with Sarkozy, the interior minister, and the torching of the mayor’s car.

“The kids didn’t burn 10 cars in that parking lot,” he said. “They just burned one: the mayor’s. They sent a political message.”

*

The Front-Line Mayor

On the night of Oct. 27, Mayor Mothron parked his Peugeot 407 sedan and walked up a ramp to a residents meeting on the esplanade. Alone.

“I go to every kind of neighborhood, no matter what time it is,” Mothron said. “I have never had any kind of personal attack. I’ll tell you how trusting I was, in the car I left my briefcase with my house keys, my credit cards, everything.”

Mothron is a solid, bespectacled 57-year-old with meaty hands. He comes from a family of vintners. His great-grandfather was mayor a century ago when the city drew Parisians on excursions to its vineyards, farms and tree-lined banks of the Seine immortalized by Impressionist painters.

Industry blossomed here after World War II and brought housing projects intended as temporary quarters for workers. The first residents were mostly French as well as Portuguese and Italian immigrants. They have largely resettled nearby in neighborhoods of close-packed houses on narrow streets, where today you find “Franco-Portuguese” cafes and posters announcing charity drives for victims of forest fires in Portugal.

New immigrants, mostly Algerians, quickly filled the Slab. The design of the seven-acre concrete village, with two blue cylindrical towers by noted architect Roland Castro, was considered audacious at the time ground was broken in the mid-1960s. The Valley of Silver embodied egalitarian planning theories of many working-class suburbs. The old-school Communist Party ran the city for a record 67 years.

But the practice of piling large, poor families on top of one another turned out to be bad policy. Decay accelerated in the 1980s. There were gang fights and small riots.

Today, 70% of the residents in the Slab are low-income. In addition to the dominant population that is of North African descent, a significant number of families come from former French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1992, the government announced a $125-million renewal plan. “A lot was spent on studies, but not much on results,” Mothron said.

In 2001, his center-right party replaced the left, which had made little progress bringing minorities into politics. In 2002, Paris earmarked an additional $330 million for public housing here. A new city hall annex, health center and steel-and-glass supermarket were built on the circular plaza at the heart of the esplanade.

“Hope returns, except that on the social side we have big problems with kids who leave school too soon,” Mothron said. “They loiter, they deal drugs, and they caused us some problems a few weeks ago.”

Mothron supports Sarkozy. But he admits he had misgivings about the interior minister’s plan to inspect a new police substation in the Slab so late that evening with a muscular police entourage. As the mayor and Sarkozy climbed an outdoor staircase into a shower of abuse, Mothron said, he realized that agitators had organized a response to the minister’s show of force.

Police identified Islamic extremists among the ringleaders, though extremists did not play a major role in the riots.

“There were shouts, craziness,” the mayor said. “It was hot. The cameras were all over it. The minister was a bit agitated. As we were walking toward the police substation, the minister said to someone on a balcony, ‘Don’t worry, we are going to get rid of this rabble for you.’ ”

Two nights later, the “rabble” sent the mayor a message in the parking lot. The 15 young men who surrounded Mothron next to the smoky wreckage were more mocking than menacing, as he remembers it.

“With a little smile, one of them said, ‘We didn’t know it was your car.’ Then they asked me: ‘Don’t you think Mr. Sarkozy’s visit and what he said got somebody mad and they burned your car?’ I told the youths that it was sleazy to do that behind my back.... I was heartbroken because of the time I have dedicated to this city.”

*

The Bootstraps Activist

When Lahcene Adalou saw the mayor encircled by young men, he did not hesitate.

Adalou waded through the group to the mayor’s side, fearing the worst. He scolded the youths, some of whom he knew from a sports club he helped run.

“They came out of nowhere, like rats,” Adalou recalled in the parking lot recently, wind ruffling strands of hair on his balding head. “I talked to them in Arabic. I said: ‘It’s Ramadan. You have no shame.’ They were embarrassed then. But they said: ‘Lahcene, what are you, Mothron’s protector? His chauffeur?’ I gave the mayor a ride home. A few days later, somebody left a threatening note on my car.”

As he told his story, Adalou, an animated, 42-year-old in a beige jacket and tie, led the way across the esplanade. In an Algerian accent, he described the improvements since he arrived 13 years ago: brighter lighting, refurbished buildings, neat new shops. To ease overcrowding and humanize the landscape, the government is demolishing some of the older high-rises that have become faded, half-empty hulks.

“It’s cleaner, safer, better,” he said, then pointed out some targets of the riots. “The Gavroche day-care center, they tried to burn that. They burned some garbage cans. They tried to burn the police station; see the black mark on the wall? There were graffiti with insults about police, Jews, Sarkozy. It made me sick.”

Adalou has an Algerian medical degree but can’t get a license here. He worked as a hall monitor in a school and saved enough to open an industrial bakery. His two daughters attend a local school.

He has become an activist. He says he speaks for families who work hard and keep their mouths shut.

With hard-nosed impatience, Adalou says young people should stop complaining.

“It’s great luck for me to be in France,” he said. “There is work here. But these kids don’t try hard enough. They were born in France. They get welfare, they get housing. Maybe they prefer to sleep until noon, make money without working.”

Nonetheless, he said, teenagers urgently need a youth center to help avoid predators, particularly religious radicals.

“It’s true, you have these fundamentalist mosques, prayer halls in basements,” he said. “France will regret letting them become so powerful.”

Since 1998, the city’s Muslim population has grown by 30%, to 20,000. Traditional Algerian worshipers attend the biggest mosque, the Al Ihsan Islamic Institute, in a dilapidated former Renault factory nearby. City officials consider the mosque moderate; its leaders helped keep the peace during the riots.

But extremists frequent at least four of the city’s smaller mosques. Police last year placed a notorious Iraqi imam under house arrest.

Adalou said he was chilled by the sight of radicals heckling Sarkozy, his hero.

“I saw them shouting, ‘Allah is great’ at Sarkozy,” Adalou said. “I was ashamed.... He’s a young, hard-working minister, and I support him. People complain that ministers spend all their time in their offices. Then when he comes, they complain it’s a provocation. Nonsense!”

*

Crossing Borders

The French agree that they must bridge the gulf between the cobblestones of Paris and the concrete of the Slab.

Some of the toughest problems have to do with intangible issues of identity and social mobility. Places like the Slab, where even a soldier can feel like a second-class citizen, need a dream.

Watching the esplanade from the community center she runs, Sadika Nhari blames both sides. Although local youths complain about discrimination, they suffer from the “everything now” attitude of a materialistic society, said Nhari, whose center is called the House for All.

“I come from an immigrant family too, but I learned how to talk in order to express myself,” Nhari said. “These kids only know how to express themselves through violence.”

Meanwhile, the bureaucracy pours money into “sensitive urban zones” but struggles to understand the people who live there.

“They don’t train the police how to talk to people,” she said. “The teachers too: They are scared, young, they come to the area full of prejudices. How can they communicate?”

The ghettos have become a political chessboard.

“Everybody’s playing the power game,” Nhari said. “Sarkozy, Islamists, political groups. Everyone says, ‘I’m the one who calmed things down.’ ”

Associations such as the House for All and Valdocco, a Catholic youth agency, try to break down barriers.

“A woman who visited our center for the first time from another neighborhood, she was very happy,” Nhari said. “She said: ‘I was worried, but it was fine. Nobody burned my car.’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.