Abu Ghraib Informer Feared a Cover-Up

HEIDELBERG, Germany — Sgt. Samuel J. Provance III began his Army career as a brush-cut idealist determined to join the Special Forces. He ended up in a military intelligence unit assigned to Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad, where he heard stories about U.S. soldiers abusing Iraqi detainees.

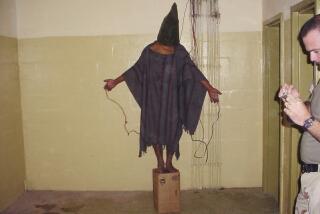

The 30-year-old Pennsylvania native said he grew troubled that prisoners were harassed, ridiculed, stripped naked and beaten. He spoke out to military investigators and last month stunned the Army when he disobeyed an order and became the first military intelligence soldier to discuss the abuse with newspapers and television stations.

Provance says he broke ranks because he believed the military was trying to cover up the scandal. Now, as the story shifts away from him, his experience is quietly turning into a cautionary tale about the price of becoming a whistle-blower. Fellow soldiers avoid him. His security clearance has been yanked. And there’s a possibility that Provance, who once studied to be a preacher, could end his Army days in disgrace with a court-martial.

“You can’t imagine the stress after I spoke out,” said Provance, a member of the 302nd Military Intelligence Battalion. “I felt the world just fall on my shoulders. I logged on yahoo.com news, and there I was in the top story block. Oh my God! The e-mails started coming. The first one I got was from a retired military police officer. He wrote, ‘Thanks for doing the right thing.’ About an hour later I got another one that said, ‘You’re a sorry soldier.’ ”

The sergeant’s choice to betray Army orders seems rooted in a confluence of naivete and a disenchantment with military protocol and the opaque rules and loyalties that govern the realm of military intelligence. Provance speaks in a near-whisper, but he possesses a steely defiant streak -- at Bible college he challenged the existence of God. At the same time, he reveres the spirit of the combat soldier; the name “Caesar” is part of his e-mail address.

Military officials, including commanders in the 302nd battalion and the 205th Intelligence Brigade, declined to comment on the sergeant’s case because of the Abu Ghraib investigation.

A senior Pentagon official investigating the prison scandal, Army Maj. Gen. George R. Fay, interviewed Provance in early May in Darmstadt, Germany. Provance ran the Abu Ghraib classified computer network and was not present during prisoner interrogations. But he told investigators it was common knowledge that intelligence interrogators encouraged mistreatment that included depriving prisoners of sleep, limiting food and stripping detainees naked to humiliate them.

In a sworn statement, Provance also said a military intelligence soldier, Spc. Armin J. Cruz, “was known to bang on the table, yell, scream and maybe assaulted detainees during interrogations in the booth.”

“This was not to be discussed,” Provance said in the statement. “It was kept ‘hush, hush’ by individual interrogators.”

Provance later testified at a military hearing in Baghdad that Spc. Hanna Slagel had told him that guards “made [male detainees] wear women’s panties, and if they cooperated, some would get an extra blanket.” Provance signed an order from his commander, Capt. Scott Hedberg, not to disclose his testimony, including statements he made in a report by Army Maj. Gen. Antonio M. Taguba in February.

That report was eventually leaked to reporters, and Provance gave interviews to ABC News, the Washington Post, Associated Press, the Los Angeles Times and other news organizations. The military whistle-blower statute protects soldiers who report abuses to members of Congress and military investigators, but it does not cover disclosures to the media.

When asked why he chose to jeopardize his career, Provance said: “I started getting bothered because innocent people were being held and they were getting lost in the system, and the military wanted to keep it secret. The abuse was being done by more than just a few bad apples. I don’t think military investigators had any interest in finding out how many people were involved.”

Military investigators asked Provance why he failed to disclose what he knew after he arrived at Abu Ghraib last fall. Fay, Provance said, told him, “You could have busted this thing wide open” if he had alerted officials earlier. The Army has informed Provance that he could face charges for not quickly divulging abuse allegations.

“I didn’t come forward earlier because I didn’t see anything,” Provance said. “It was just things I had heard. If somebody denied it, I’d have looked pretty stupid. I’d be the boy who cried wolf.”

He said he spoke up when he believed that other soldiers interviewed by military officials at Abu Ghraib were recounting similar stories.

The other day, Provance sat in an Italian restaurant in downtown Heidelberg. He wore bluejeans and a T-shirt streaked with the name of the rock group Nine Inch Nails. With a trace of Southern drawl, he spoke about the circumstances that led him to the Army.

Provance was born in Fayetteville, Pa., and raised in Williamsburg, Va., by his mother and stepfather, a former Marine who managed a hospital storeroom. He said he moved out on his own at 16, living in a motel and working as a stock boy in a department store. He received a high school general equivalency diploma in 1992, took a job at a Dunkin’ Donuts outlet and attended Green Springs Pentecostal Chapel.

With the aim of becoming a preacher, Provance enrolled in Holmes Bible College in Greenville, S.C. He stayed three years, quitting, he said, after raising too many questions about faith and fundamentalism.

“I was kind of like the rebel,” he said. “I needed reasons for things, and they questioned my faith. I didn’t want to become a drone. I left.”

In 1998, Provance joined the National Guard in Clemson, S.C. A year later, he enlisted with the active-duty Army and was assigned to the air missile defense unit of the 101st Airborne Division at Ft. Campbell, Ky. His dream was to join the Special Forces, but he scored low in physical training and navigation.

“I was pretty devastated,” he said. “That was to be everything in my military career. I got bitter. But then I began to see things from their rationale.”

Provance was reclassified as a military intelligence analyst, and in November 2002 he joined the 302nd battalion under the V Corps in Heidelberg. The 302nd shipped to Kuwait in February 2003 and arrived in Iraq two months later. Provance said he thought he would enjoy the intrigue of intelligence work but quickly discovered he wasn’t suited for his unit’s internal politics and lacked training on several computer programs.

“From the get-go, I had problems with them,” he recalled. “The intelligence guys didn’t care about the 101st Airborne. They didn’t care about Special Forces. They were all about computers and PowerPoint presentations. To me, they were less soldiers and more analysts in uniforms.”

After disagreements with his commanding officer, Provance was transferred to another platoon. “I complained to the Army inspector-general about my superior officer,” he said. “There was nobody sticking up for me.”

Last September, Provance and other members of his unit were assigned to Abu Ghraib to replace soldiers who were killed and wounded in mortar attacks.

It was there, he said, that interrogators told him and others about widespread mistreatment of Iraqi detainees. “I didn’t know at the time,” Provance said, “how humiliating that is for Arab men to be naked. I just know I couldn’t strip someone buck naked. I always thought, ‘What if I were a prisoner? Could I endure that?’ ”

After he informed investigators of the alleged abuse, Provance said he felt he was being penalized for telling the truth. He went public, he said, when he suspected that the military was limiting its investigation to low-ranking military police at Abu Ghraib and not probing the involvement of interrogators and higher-level officers.

“All the proper military channels are broken,” he said. “Doing it inside the Army doesn’t get it done. It only gets me hurt. Military intelligence as I’ve experienced it is shady and under the table. Nothing is honest and straightforward.”

Provance’s military future is uncertain, and he acknowledges that his career may be over. He has found support from people he’s never met. Former Vice President Al Gore mentioned Provance’s name in a speech condemning the abuse at Abu Ghraib. Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.), a member of the Armed Services Committee, is following Provance’s case.

“It is important every military member understand that not only is it the right thing to report misconduct, it is required as part of their duty,” read a statement Graham sent to the Stars and Stripes newspaper. “In speaking with Sgt. Provance, I sought to assure him that in providing testimony before a court-martial, he was doing his legal duty.”

Sometimes, Provance said, he believes his troubles will go away and he’ll be reassigned to a combat unit, far from the layered, confusing world of military intelligence.

“I want a combat posting,” he said. “To me, that’s the Army I know is true.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.