New Low for Hated Former Leader

MEXICO CITY — During his long public career, Luis Echeverria managed to anger and alienate nearly every sector of Mexican society, from wealthy businessmen to left-wing student activists.

The Mexican media called him “the Preacher,” and as president from 1970 to 1976 Echeverria espoused a gospel of revolutionary social reform. When he left office, his country was reeling from rising inflation, ballooning debts, a falling peso and social convulsions.

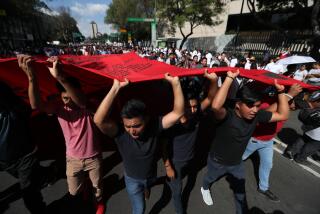

Now, nearly 30 years later, Echeverria, 82, is again at the center of controversy, this time involving his alleged connection to the 1971 massacre by right-wing paramilitaries in which up to 280 people died or disappeared in Mexico City.

On Saturday, a criminal judge dismissed charges brought last week by a special prosecutor. The special prosecutor says he will appeal, although most analysts here believe it is unlikely that Echeverria will face jail.

Whatever the final outcome of the legal dispute, Echeverria’s standing in Mexican history hardly could sink much lower.

“He’s one of the most unpopular presidents we’ve had, he and [Jose] Lopez Portillo,” said Sergio Sarmiento, a columnist for the Mexico City newspaper Reforma and a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. He was referring to Echeverria’s successor as president.

As a young man, Echeverria had shown considerable promise. Born Jan. 17, 1922, in Mexico City, he earned a law degree in 1945 and two years later joined the faculty of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where he taught political theory. In 1946 he joined Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, and quickly rose to become private secretary to its then-president, Gen. Rodolfo Sanchez Taboada.

In “Mexico: Biography of Power,” writer and historian Enrique Krauze says Echeverria was a loyal, even “servile” party member before he became president.

He “seemed like a perfect Mexican patriarch, with nine children and an accomplished wife,” the daughter of a powerful politician, Krauze writes. “He offered himself as the model Mexican, stepped down into life from a mural by Diego Rivera.”

Many of those personal traits persisted throughout Echeverria’s career. “All the presidents had girlfriends and had whatever love relationships. Echeverria never did,” Sarmiento said. “He had a very close relationship with his wife. He was the kind of person who would work from 7 o’clock in the morning to 2 o’clock the next morning and never stop.

“Even 20 years later or 30 years later, it is clear that he is an obsessive person. He has a remarkable memory. He remembers every political debt and every insult he ever received in his life.”

An episode from his tenure as interior secretary has shadowed Echeverria. On Oct. 2, 1968, as Mexico City was preparing to play host to the Olympic Games, federal troops opened fire on student demonstrators in the Plaza de Tlatelolco in north-central Mexico City. Hundreds were believed killed, human rights activists say. Hundreds more demonstrators were arrested and imprisoned.

Echeverria later insisted that he had dispatched troops to the protest to maintain order. Those who were arrested, he said, were common criminals.

“Not one was arrested for writing a novel or a poem or for his way of thinking,” he told an interviewer.

Last October, a criminal inquiry into the Tlatelolco massacre found evidence that some of the snipers passed through the apartment of Echeverria’s sister-in-law, Rebeca Zuno de Lima, who lived in a residential tower near the plaza.

Despite some damage to his reputation, Echeverria gained the PRI’s presidential nomination in 1969. The PRI’s political monopoly ensured his election. Nonetheless, he set off on a 35,000-mile national campaign swing on a bus named for Miguel Hidalgo, a leader of Mexico’s war of independence from Spain. Along the way, he promised new schools, roads and hospitals to Mexico’s peasants.

“In essence you have all the contradictions of the PRI built into Echeverria,” said Peter Hakim, an expert on Latin America and president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based think tank. “The PRI brooked no opposition. At the same time it had this populist bent.”

As president, Echeverria sought to cast himself in the mold of Lazaro Cardenas, Mexico’s popular leader of the 1930s. But he lost credibility with the leftist intelligentsia after the 1971 massacre, when he failed to follow through on his promise to seek justice against its perpetrators.

He also infuriated Mexico’s conservative business elite with his nationalist economic policies. Under his leadership, the government bought majority stakes in the mining and telephone sectors, put strict limits on foreign investment and passed laws setting aside the oil, electricity, railroad and other strategic industries for the state. He expropriated millions of acres of farmland from private hands and redistributed them to peasants.

When Mexican industrialist Eugenio Garza Sada was killed by a communist guerrilla group as part of a botched kidnapping attempt in 1973, the businessman’s widow refused to greet Echeverria when he showed up to pay his respects, said George Grayson, an authority on Mexican politics at the College of William and Mary. Undeterred, Echeverria attended the graveside service only to have a speaker castigate the government for fomenting hate and division between social classes.

“Rarely has the chief executive of any country been subject to a more studied insult,” Grayson said.

Echeverria also rankled the United States with his vision of a new economic order in the hemisphere that called for Latin American unity to counter U.S. “expansionism,” and he was friendly with Cuban dictator Fidel Castro and Chile’s Marxist president, Salvador Allende.

Echeverria also criticized Israel, condemning Zionism as a racist policy and allowing the Palestine Liberation Organization to open an office in Mexico City. In response, U.S. Jews organized a tourist boycott of Mexico, a move that Grayson said caused the cancellation of 30,000 hotel reservations and the loss of an estimated $200 million for the Mexican economy.

“He was involved in shutting down or cocooning the economy and discouraging investment,” Grayson said. “Mexico even today is suffering from the policies and appointments of Luis Echeverria.”

Echeverria became a less visible figure in recent decades, though as Mexico’s oldest surviving president, he became, by default, an elder statesman in the PRI. Over the years, he has served as ambassador to Australia, representative to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and run a Third World studies institute.

“Echeverria was a power-crazed person,” Sarmiento said. “He dedicated his entire life to politics. He still does that even though he’s over 70. Everything he did had to do with politics.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.