Ex-Teacher in Student Rape Leaves Prison

SEATTLE — Mary Kay Letourneau, the former schoolteacher who had two children by the student she was convicted of raping, quietly walked out of prison Wednesday.

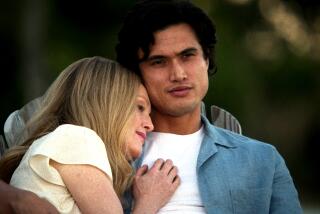

After serving 7 1/2 years for child rape, Letourneau, 42, slipped unseen past the gathered international media camped outside the Washington Corrections Center for Women about 24 miles southwest of Seattle. She maintains that the relationship with her student -- who was 12 when she began having sexual contact with him -- was mutual love.

As a condition of her release, Letourneau is prohibited from seeing or talking with Vili Fualaau, now 21. However, both have indicated they intend to resume contact and to raise their two young children together.

Early Wednesday afternoon, Fualaau attorney N. Scott Stewart filed a motion in King County Superior Court to dissolve the no-contact order. The motion, in part, states that Fualaau “is now an adult and, as an adult, is requesting that the court allow him to associate with other adults of his own choosing, specifically Mary Kay Letourneau.”

The prosecutor’s office is reviewing the motion.

Letourneau must register as a sex offender, receive counseling and submit to state supervision. Authorities will notify neighbors wherever she settles.

Anne Bremner, a Seattle lawyer and a friend of Letourneau’s who has had regular contact with her during her incarceration, described her as an exemplary inmate.

She said Letourneau sang in the choir, tutored other prisoners, expanded the textbook collection and regularly attended Catholic Mass.

Bremner said Letourneau was considering work as a prisoner advocate, but her first priority will be to renew bonds with her six children -- four with her ex-husband, who lives in Alaska, and the two daughters, 5 and 7, with Fualaau.

Letourneau said she would consider having more children with Fualaau.

“If we are so blessed to continue a relationship and that’s what he wants, for him I would,” Letourneau told a local news station shortly before her release.

Fualaau told a television reporter at Sea-Tac International Airport on Tuesday that he still loved Letourneau, but that he was “kinda nervous” about what the future held. Fualaau, like many of the players in the Letourneau saga, hit New York’s talk-show circuit Wednesday.

Letourneau grew up in Orange County and is the daughter of the late former Republican Rep. John G. Schmitz. She was a married mother of four, teaching at Shorewood Elementary School in Burien, a small, working-class town about 14 miles south of Seattle, when she first met Fualaau in her second-grade class.

Letourneau described the boy as artistic and intense, and in search of a mentor. She took up the role, teaching him piano, encouraging his drawing and even attending an art class with him. The boy spent a lot of time in the Letourneau family, even traveling with them to Alaska.

The sexual contact began in 1996, when Fualaau was in sixth grade and Letourneau, then 34, was his teacher.

Her husband, Steve, learned about it after finding love letters that his wife had written; one of his relatives reported it to police.

When Letourneau was arrested in 1997, she was pregnant by Fualaau. A judge sentenced her to six months in jail for second-degree child rape, and ordered her to stay away from the boy. A month after Letourneau was released, she was caught by Seattle police having sex with Fualaau in her car.

She was sentenced to seven years and gave birth to Fualaau’s second daughter behind bars. Friends said that while in prison she pumped breast milk into plastic bags for her infant daughters, who were placed in the custody of Fualaau’s mother, Soona Vili.

After Letourneau was arrested, Fualaau defended her and claimed not to be a victim. Then in 2002, he and his mother sued the school district and police for $1 million for failing to protect him from Letourneau. Jurors did not award any money, and the Fualaaus were criticized as greedy.

During the civil trial, and subsequent interviews, it was revealed that Fualaau took drugs, had an alcohol problem and had been fired from a restaurant job. A high-school dropout, Fualaau is now working on his general equivalency diploma. He is unemployed and, friends say, spends much of his time with his daughters.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.