Ultimate takedown

As legions of fans count down to the biggest event of the year, Wrestlemania XIX at Safeco Field in Seattle on Sunday, the age-old question about professional wrestling -- is it authentic? -- has been replaced by a more significant one: Is it deadly? Yes, the competition that fills arenas and prompts millions of pay-per-view buys is scripted, but the danger is real -- 24 current or former professional wrestlers age 45 or younger have died since 1997.

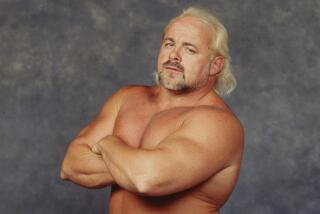

One of the latest, Curt “Mr. Perfect” Hennig, was found dead in his Brandon, Fla., hotel room the afternoon of Feb. 10, hours before he was scheduled to take part in a show at the Tampa State Fairgrounds. The official cause of death was “cocaine intoxication,” which caused a fatal heart attack, according to the medical examiner. An autopsy revealed an enlarged heart and Hennig’s family said he had a history of an irregular heartbeat, but his father is convinced there was another significant factor.

“Wrestling had a major part in my son’s death,” he said.

Hennig, 44, had fallen from pro wrestling’s top echelon in recent months -- he was fired last June by World Wrestling Entertainment, or WWI, the industry’s major league, after an altercation with another performer away from the ring -- but previously he had been one of its most popular and innovative performers. His routine was less preening and flexing than it was an exhibition of quick and jolting power moves, jumps, dives and body slams.

The fans loved him, and Vince McMahon, architect of the WWE, rewarded him with the “Perfect” nickname -- and a salary of nearly $1 million a year.

But while lucrative, Hennig found life as a professional wrestler far from perfect. The work was constant, with little or no time to heal from injuries suffered in a seemingly never-ending quest to look great while trying stunts even more outrageous than the night before.

Larry Hennig, known as “The Axe” in his own pro wrestling career, acknowledges the demands placed on his son: “Sometimes the dollar is more powerful than the body and mind. A lot of people don’t realize what these guys go through.” Pain pills and steroids “are part of the business.” And he added, “There seems to be a pattern here. The pressures, this ‘live hard, die young’ mentality, is definitely out there.”

Indeed, Dave Meltzer, an industry watchdog and editor of the weekly magazine Wrestling Observer, estimates that most of the young men who died engaged in abuse of steroids, prescription drugs and/or human growth hormone -- risky behavior he says was compounded by job stress, recreational drug use and bad diet habits.

The wrestling lifestyle, it seems, is not conducive to a long, healthy life.

Show goes on

Only hours after Curt Hennig’s death in Florida, a jumbo television screen at Staples Center, fitted atop a stage constructed for the WWE’s nationally televised “Monday Night Raw” event, flashed his image with the message, “In memory of....”

“Did he die?” a fan in a floor seat asked a friend.

But before there was time for an answer, a roar of guitar riffs and fireworks prefaced the introduction of the show’s “plot,” one that event organizers surely considered less vexing: Would WWE chief McMahon really fire his general manager, Eric Bischoff?

So it goes in the fast-paced, high-stakes major league of professional wrestling, which last year generated $425 million in revenue. There is little time for sentiment, or, critics say, oversight on health issues that exist in other sports-related and entertainment businesses. Calls for more emphasis on the safety and welfare of wrestlers are lost in an insatiable drive to broaden business and make money. Death and drug use are taboo topics for “the talent,” which is what the wrestlers are called by the handlers who shelter them from questions on such issues.

McMahon, who refused multiple interview requests until Friday, reacted angrily to criticism that he turns his head from health and safety matters. “I’m a human being and a businessman,” he said. “If people die, they can’t perform for you. From the human being’s perspective, how do you think I feel? Do you think I’m the ... devil?”

McMahon said some of the deaths were tied to a decades-old mentality of former wrestlers who “still crave the parties, the attention, the sex, drugs and rock and roll that was part of our business and no longer is now.”

But others say not much has changed.

“It’s a syndrome, an interrelated, vicious cycle,” Bruce Hart, a veteran trainer who has worked with several of the dead wrestlers, said of the business.

“There’s a demand to look a certain way, constant pressure to build and maintain a career, and it’s a business that requires a ton of travel, a lot of physical punishment and a ton of personal appearances. It’s an invitation for these guys to take something to deal with it: steroids, painkillers and other drugs.”

Meltzer described Hennig as “a good ol’ boy” who popped pain pills and used steroids to maintain his place as a wrestling star. “It was no secret he had all kinds of back and knee injuries,” Meltzer said. “He used to work six to seven nights a week -- good, hard, 15- to 20-minute matches. He was known for that toughness.”

The WWE -- at that time the World Wrestling Federation, or WWF -- instituted a random drug testing policy in 1992, about a year after evidence introduced in a Pennsylvania trial established a link between steroids and the highest levels of professional wrestling. But four years later, citing a cost it considered prohibitive and the emerging threat of a rival organization that did not require testing, the WWE scrapped its policy.

What’s left is a clause in a wrestler’s contract requiring them to submit to drug testing should there be “just cause,” from tardiness or other erratic behavior.

Deaths have similar ring

Professional wrestling officials liberally estimate there are about 1,000 performers 45 and younger who have worked on the major- or minor-league circuits since 1997. Of the 24 who have died, only three -- Gary Albright, Owen Hart and Curtis Parker -- have died from calamities suffered during wrestling action.

Albright had a heart attack in 2000. Hart died in a fall in Kansas City a year earlier, when a shackle device broke as it was lowering him into the ring. Parker died last year after being dropped on his head during a practice session.

But the demanding, heavily choreographed action of professional wrestling matches is not what has critics most worried. It’s what happens before and after.

Consider the details in a few of the deaths:

* “Bad Boy” Basil Bozinis, a 27-year-old from Venice who competed on the El Segundo-based Ultimate Pro Wrestling circuit, died in February 2002 from a drug overdose. Heroin, cocaine, methamphetamines and the painkiller Nubain were found in his system. UPW President Rick Bassman told investigators Bozinis was a steroid user.

* Bobby Duncum, 34, a former Global Wrestling Federation tag-team champion, died in 2000 from a drug overdose that a Travis County, Texas, medical examiner said included alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, valium and the painkiller fentanyl.

* Richard C. Wilson, 33, a former World Championship Wrestling performer known as “Renegade,” had more than twice the legal limit of alcohol in his system when he shot himself to death in Cobb County, Ga., in 1999.

* Also in 1999, “Ravishing” Rick Rude, 41, died in bed at his home in Fulton County, Ga., of a drug overdose medical officials said included valium and gamma-hydroxybutrate, the so-called “date rape drug” -- used by athletes to quicken their recovery from weightlifting sessions.

McMahon noted that several of the deceased were minor leaguers not affiliated with his organization. “I have nothing to do with the vast majority of these 24 guys,” he said. Added Jerry McDevitt, an attorney for the WWE: “Guys are dying after financial, drug and marital issues. That has nothing to do with wrestling. That has to do with life.”

Enlarged hearts, hardening of the arteries and other “natural causes” are the reasons most often identified by medical examiners in the wrestlers’ deaths. Those symptoms have been associated with steroid use and, in some cases, that connection has been cited.

One such case is that of “The British Bulldog” Davey Boy Smith, a former champion who died last May at age 39 while vacationing in Invermere, Canada. Smith’s final autopsy report is pending, but a regional coroner said the preliminary cause of death is hypertrophy -- an enlarged heart, with evidence of microscopic scar tissue possibly from steroid abuse.

Smith’s ex-wife, Diana, has said he abused steroids and, after he suffered a back injury in the ring in 1998, relied on morphine.

WWE representatives acknowledge that Smith was twice sent to drug rehabilitation centers but they say he was a reluctant participant. “We led that horse to water,” said Ed Kaufman, general counsel for the WWE. “At some point, it’s up to him to take a drink.”

No rest for the weary

Rob Van Dam smiled, flexed and applied dozens of fake chokeholds at a recent promotional appearance that attracted more than 500 fans at Montclair Plaza. He answered a few questions from a reporter, too, but only after rules were set by a handler: “No questions about steroids or any negative stuff.”

Van Dam is a 13-year pro who successfully navigated his way up the chain of wrestling’s loosely organized minor leagues.

But now that he’s made it, his schedule is even more hectic. He said the previous four days had gone this way: Friday, the 31-year-old flew from Los Angeles to Miami for a Saturday event. Sunday, after another flight, he wrestled in Pittsburgh. The next day, he was in Baltimore for a “Monday Night Raw” episode, which is televised weekly by cable network TNN. Now, Tuesday, he was back in Southern California for the personal appearance.

“It’s challenging to squeeze in time for rest, my workouts and home duties, but I can handle it,” he said.

Jim Ross, a WWE executive and broadcaster for “Monday Night Raw,” said wrestlers from past eras might have been criticized for asking for a day off, but not anymore. “We want our guys to have a happy home life,” he said. “That makes a better employee.”

But others paint a more sinister picture, one in which even superstar performers are reluctant to miss a match or even an appearance no matter what the excuse.

“There is fear of repercussion, and that just doesn’t happen in other sports like the NFL or major league baseball,” said Marcy Engelstein, a personal assistant to former WWF world and tag-team champion Bret “The Hitman” Hart.

Hart is struggling to regain left-side motor skills as he recovers from a May 2000 stroke, an injury Engelstein alleges he was predisposed to because of a concussion he suffered during a match five months earlier. She said Hart was ignored when he expressed concern for his health to a trainer and a television director, and he worked steadily for weeks until being properly diagnosed. A short time later, he suffered another blow to his head when he fell off a bike, after which he had the stroke.

“What big-time wrestling needs is to be unionized,” Engelstein said. “Bret has tried to ratchet up the attention for the need for better protection, but achieving solidarity is tough.... Everyone is afraid for their positions.”

Steroids a shortcut

Some of the biggest names in pro wrestling have admitted using steroids, including McMahon, who will wrestle Sunday; TV action figure Hulk Hogan (whose real name is Terry Bollea); and Jesse “The Body” Ventura, the governor of Minnesota.

In his book, “I Ain’t Got Time to Bleed,” Ventura wrote, “I would take testosterone for 30 days, then I’d go off it for six to nine months.... I later found out they were destructive.”

Hogan was implicated during the trial of Dr. George Zahorian, a Harrisburg, Pa., urologist who in 1991 was convicted on 12 counts of distributing steroids for nonmedical purposes. Zahorian testified Hogan was a user, and a grand jury obtained Federal Express records showing the doctor sent eight packages to him in a nine-month period. The same records showed 34 deliveries from Zahorian to WWF offices and eight more to McMahon at various addresses.

Charged in 1993 by a grand jury with conspiring to distribute steroids to wrestlers -- he was acquitted -- McMahon responded by hiring Dr. Mauro DiPasquale, a certified medical review officer, to establish a drug testing system for the WWF.

“He needed a cleaner sport and I was there to structure a policy that would deliver that,” said DiPasquale, who added that McMahon never interfered with his work. “We targeted all anabolic steroids, narcotics and stimulants. It was complete. I knew if they were taking codeine or aspirin.”

By terms of the program, each WWF wrestler submitted to two random tests a month. The first positive test resulted in a conference; the second a suspension without pay for six weeks to three months. A third positive initiated a yearlong ban.

“Testing was good for them,” DiPasquale said. “No steroids was an incentive to train properly, eat properly and live a cleaner existence. Steroids are the great equalizer. You can eat [terribly], party and still look good.”

In nearly four years, DiPasquale said, about a dozen wrestlers were suspended -- four of them, including one of the organization’s stars, for a year. Then, in October 1996, McMahon pulled the plug on the program, telling associates the cost was too high and that the WCW, which didn’t test its wrestlers, was threatening business.

“The WWF guys were losing their size,” DiPasquale said. “I think there was a line of thinking out there that, ‘If we take away the freaky look, what have we got?’ ”

DiPasquale said he has tracked wrestlers’ deaths with regret.

“Knowing human nature, I suspect [wrestlers] are using steroids again, but there’s no way these deaths are due 100% to steroid abuse,” DiPasquale said. “You have to look at the other factors. These are heavier, muscular people and the weight alone increases mortality. They eat [junk], making their cholesterol level higher, and they lead rough lives, which leads to prescription drug abuse and recreational drug abuse.”

McDevitt, the WWE’s attorney, said the testing accomplished what was intended: to inform the wrestlers how seriously the organization wanted to end illegal drug use. He also opined that most drug testing programs are more IQ challenges -- being smart enough to work around testing -- than effective identifiers of drug use.

“We know we can’t police our people any better than any other company can,” McDevitt said.

Lack of attention

Oversight of professional wrestling shows in most states is the responsibility of local athletic commissions, which have typically lax pre-match requirements.

In California, the state athletic commission requires neither copies of health records nor a pre-competition physical examination. In New York, performers are subject to a medical exam that usually is nothing more than a blood pressure test.

Oregon offers the most scrutiny, and it hasn’t had a WWE or WWF event in seven years. Jim Cassidy, executive director of Oregon’s boxing and wrestling commission, said the state requires screening for drugs including cocaine, amphetamines and marijuana 30 days before competition -- a requirement WWE officials say is a major roadblock because of the cost of sending wrestlers in to be tested.

But skipping Oregon hasn’t been much of a hit to WWE business. In 2002, the company reported 7.5 million pay-per-view buys, released 26 DVDs and circulated 7.5 million magazines. And after drawing 2 million fans last year, there are some 340 live events planned this year. Wrestlemania averages 1 million pay-per-view buys.

While describing fatalities among wrestlers as “alarming,” former WWF star Ted “The Million Dollar Man” DiBiase, a traveling evangelist, said he believes McMahon will eventually investigate.

But, he added, “McMahon and the industry are not telling these wrestlers to engage in this reverse bulimia. It’s self-induced. The line of thinking, ‘This body is who I am. Without it, who am I?’ is out there.”

And what might curtail that thinking?

“That,” said “The Million Dollar Man,” “is the million-dollar question.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.