‘Win One for the Cowboy’ Is Still a Battle Cry in Anaheim

Baseball is a game of statistics, but fans will tell you it’s also a game of superstition, in which changes in ritual invite changes in luck and fresh socks can suck the life out of a winning streak.

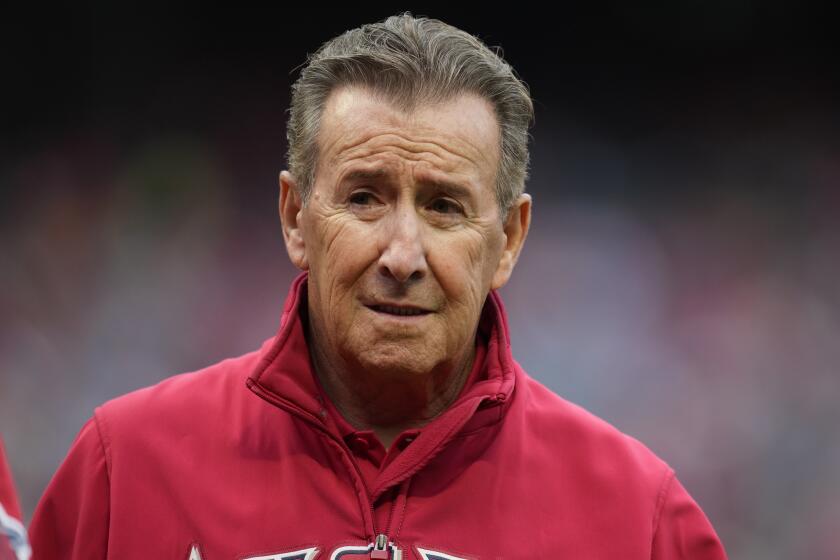

So it’s not that much of a leap for high-flying Anaheim Angels fans to believe late owner Gene Autry is still around, a guitar-strumming angel in the outfield shepherding his beloved team through its surprise run for the World Series.

“I do feel it,” said Russ Frazier of Lake Forest, a board member of the Anaheim Angels Booster Club. “I think there’s an emotion that has been carrying on for a long time to see it done, to see them win one for the Cowboy. They’ve got an angel up there negotiating with St. Peter to do something for us down here.”

If the team has a guardian angel, it’s Autry, the onetime Oklahoma telegraph operator who mixed a gentle singing voice and a romanticized vision of the Wild West to create an entertainment juggernaut.

When he was done singing and acting, Autry made the conversion to entrepreneur, amassing a fortune through investments, broadcast outlets and real estate.

But before the money, almost before the singing, there was baseball.

As a youth, Autry was such a promising player that the St. Louis Cardinals offered him a tryout. Music and the movies became his career, though.

Beginning with “In Old Santa Fe” in 1934, Autry appeared in more than 90 films and made more than 600 recordings, including the first certified gold record, “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine,” released in 1932, and the first platinum record, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” released in 1949.

When Autry became rich enough, he indulged his early love and in 1960 bought his own baseball team--the expansion Los Angeles Angels--in a roundabout effort to gain sports programming for his radio stations.

Autry styled himself as the kind of owner who hired people to run his team, then let them do their jobs while he enjoyed the games. Autry became a fixture, sharing the bench with managers and players during batting practice, then keeping score from the owner’s suite during games.

It was a vexing love. The Angels reached the playoffs three times during Autry’s tenure and lost each time. In 1996, advancing age and a quantum shift in the economics of the game led Autry to sell to Walt Disney Co.

He died two years later on Oct. 2, 1998, a week after the Angels were eliminated from the American League West playoff race.

Even in death, Autry remains the soul of the team for many fans, an affection that grew from his overt love for the game and his openness.

“He had such a personable attitude with both the players and fans that he was like a father figure, really,” said Barbara Phillips, an Angels fan since the early 1980s. “That’s kind of the feeling that has carried over with the fans when they say to win one [World Series] for Gene.”

More than an owner, Autry was the visible face of the team in a sport dominated by athletes chasing the next big contract. The players came and went, but Autry was always on hand, sharing the annual disappointments with fans.

Autry’s entertainment background helped bridge the customary divide between owner and customer. At ease with fans, Autry sought out their company. Longtime Angel boosters tell of running into Autry in Palm Springs and then Tempe, Ariz., during spring training, where they shared late-night drinks and cowboy songs in hotel bars and restaurants.

The Angels, under Autry’s ownership, also arranged off-season ocean cruises in which fans--including Phillips--mingled with players and their wives, forging deeply rooted connections. To this day, many fans have autographed pictures of Autry to go along with those of favorite players.

“One time, the boosters had a get-together up in his dining room in the stadium,” Phillips said. “He came up to see what was going on, and he was such a delightful man he even sang for us. How down to earth is that?”

The No. 26, representing Autry’s symbolic standing as 26th player on a 25-man roster, hangs in the outfield at Edison International Field, and a life-size Autry statue--right hand thrust forward in a welcoming greeting--stands inside the stadium.

“The Angels were an extension of him,” said Jeff Horel, 26, of Huntington Beach. “He was more than an owner, he was folk hero.”

Autry’s continuing popularity, even after his death, adds an extra texture to the predictable fan yearning for a successful season.

“I do think they are all hoping and praying that this year will be what Gene had hoped for all along,” Phillips said. “But the memories that Gene implanted in the club, that will probably always be there even if they don’t win.”

Eli Grba was Autry’s first Angel, taken from the Yankees in the 1960 expansion draft and the starting pitcher in the Angels’ inaugural game, a 7-2 victory over the Baltimore Orioles on April 11, 1961.

From his home in Athens, Ala., Grba has watched the Angels’ playoff progress--including their surprise elimination of the Yankees, a series that gave Grba two teams to root for. He leaned toward the Angels, in part because of Autry’s legacy.

“I’ve always been a guy that sticks for the underdog, and when we got there [in ‘61] we were the underdogs,” said Grba, who ended a sporadic career as a minor league coach in 1997. “And Gene Autry was a wonderful man. He treated me very well. He used to come to my house when I lived near LAX and we were playing at [Los Angeles’] Wrigley Field.”

That ballpark, which used to stand in South-Central Los Angeles, was torn down in the mid-’60s after the Angels moved on, first sharing space at Dodger Stadium then heading to Anaheim in 1966. Grba’s affection for Autry and the Angels remains, and he sides with the faithful in their belief that 41 years of jinxes, under-performances and physical flops are over.

The Cowboy will sing again.

“I believe in the hereafter and all that, within reason,” Grba said, laughing over the telephone. “It’s destiny that they’ve gotten this far.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.