Polanski’s ‘Pianist’ Wins Palme d’Or

CANNES, France--There’s just no figuring the Festival de Cannes.

Headed by the norm-breaking David Lynch and faced with a competition slate that was nothing if not adventurous, the jury at the 55th festival gave its top prize, the Palme d’Or, to perhaps the most conventional film on the docket, Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist.”

Based on the true story of Polish Jewish pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman, “Pianist” stars Adrien Brody as the musician whose good luck and grit enabled him to survive years in hiding in anarchic Warsaw during World War II. Though its Holocaust horrors are familiar, “Pianist” improves as it progresses, and being able to tell a story with echoes of his own clearly moved the somber director, who told an excited crowd at Sunday’s ceremony that he was “honored and proud” to receive this award for a film that depicted his native Poland.

“I always knew that one day I would make a film about this painful chapter in Polish history, but I didn’t want it to be autobiographical,” Polanski wrote in a director’s statement. “I survived the Krakow ghetto and the bombing of Warsaw, and I wanted to re-create my memories from childhood.”

Two American films took home major awards. Paul Thomas Anderson, whose “Punch-Drunk Love” starring Adam Sandler and Emily Watson charmed French critics as well as festival audiences, shared the best director prize with veteran Korean filmmaker Im Kwon-Taek, whose “Chihwaseon” told the story of a celebrated 19th century Korean painter.

An elated Anderson told the crowd at the Palais du Festival, “If you’re a young boy growing up loving movies, you always want the French to love your movies. So thank you very much.”

Winning a specially created and unanimously given “55th Anniversary Prize” was Michael Moore for his provocative documentary examination of violence in America, “Bowling for Columbine.” Looking not very happy to be in a tuxedo, Moore first noted that President Bush has just arrived in France and wondered if the festival could set up a special screening for him. Then, admitting “I forgot most of my French from high school,” Moore launched into an extended thank you in that language that displayed more fearlessness and nerve than correct pronunciation and was much commented on by succeeding award winners.

Paul Laverty, for instance, who won the screenplay prize for Ken Loach’s gritty and immediate “Sweet Sixteen,” started with a few words in French and added, “I’m really glad my French teacher’s dead; this would have finished him off if Michael Moore hadn’t finished him off first.”

“Sweet Sixteen” is one of Loach’s strongest, most affecting works, starring a debuting Martin Compston as Liam, determined to find a place to live for his mother when she’s released from prison in time for his 16th birthday. But though Liam is enormously likable and clearly capable and ambitious, in a world that lacks both opportunity and moral anchors, the only avenue he can see open for him is selling drugs. Equally unreserved was unpredictable Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki, whose “The Man Without a Past” was the only film to receive two prizes, the Grand Prix, considered to be the runner-up award, and the best actress prize for his veteran actress Kati Outinen. Having done a poker-faced soft shoe up the steps of the Palais, Kaurismaki ambled up to the podium from his seat like a grouchy Finnish bear and said, as the rhythmic applause died down, “First of all, I would thank myself. Second, the jury.”

Kaurismaki’s film, a riff on traditional 1940s melodramas about an amnesiac trying to find a new life, is a fine example of both the director’s deadpan humor, familiar to film festival audiences in films such as “Leningrad Cowboys Go America” and “Drifting Clouds,” and the amusing I-Walked-With-a-Zombie acting style he prefers.

Taking the jury prize as well as the International Critics Prize was the Palestinian film “Divine Intervention.” Written and directed by and starring Elia Suleiman and subtitled “A Chronicle of Love and Pain,” the film brings an angry poet’s surreal and absurdist touch to the impossible Middle East situation, the equivalent of Jacque Tati of “Playtime” joining up with the Palestinians.

Taking the best actor prize was Olivier Gourmet for “The Son,” another neo-documentary work by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (“The Promise”), whose “Rosetta” won the Palme d’Or in 1999. Shot in an intense, almost claustrophobic style (Gourmet thanked the brothers for doing such a good job photographing his ears and the back of his neck), this unapologetically demanding film stars the actor as a taciturn woodworking teacher who turns out to have a terrible secret connection with one of his new students.

Though its turgid dramatury probably kept it from winning anything, “Russian Ark” is a visual astonishment. It consists of a single, uncut steadycam shot lasting 87 minutes that sinuously swoops through dozens of spaces in St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum. Directed by Alexander Sokurov, who says he got the idea because “I’m sick of editing” and shot by Tilman Buttner, the steadycam operator on “Run, Lola, Run,” “Russian Ark” utilized 867 actors, hundreds of extras, years of planning and seven months of rehearsal time, all pointing to a one-take, all-or-nothing shooting day. The film’s dramatic meditation on Russian history is murky and uninvolving, but given the technical challenges met, it is hard to get overly upset.

Though it also did not win anything, a reluctant word should be said about Gaspar Noe’s “Irreversible,” the officially designated shock item--complete with a warning that “This film may contain scenes that could disturb some of the spectators” printed on admission tickets in English as well as French--which no Cannes can be without. Actually, that warning is rather feeble, given the meretricious nature of this unrelenting piece of business which stars Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel and has as its centerpiece a horrific nine-minute rape scene that demeans and humiliates spectators and filmmakers alike. “Irreversible” has taken “time destroys everything” as its motto, and it’s nice to know this film will not be exempted.

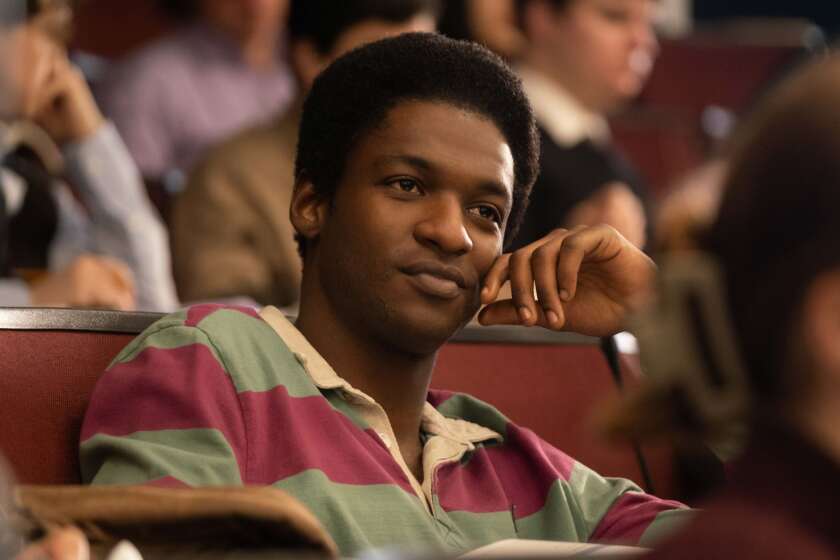

As has become something of a tradition at Cannes (think “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” two years ago), some of the most involving and entertaining films in the festival are official selections presented, for reasons difficult to fathom, out of competition. This was the case with the vivid, engrossing “City of God,” a Brazilian film directed by Fernando Meirelles, one of that country’s top commercials directors, who put his visual dazzle at the service of an epic saga of social realism set over three decades in one of the ultraviolent favelas or slums of Rio de Janiero.

A hot-wired marriage of authenticity and style, replete with young characters with names like the Tender Trio, the Runts and Knockout Ned, “City of God” is both chilling and exhilarating. Meirelles and co-director Katia Lund did workshops for months with more than 100 kids to mold performances from their nonprofessional cast. The result was an immediacy, a sense of place and of danger that few films at the festival matched.

Equally entertaining, and the complete opposite of realistic, was the irresistible “Devdas” from India, the first singing-and-dancing Bollywood-style film ever invited to Cannes and the most expensive one ever produced. Starring former Miss World Aishwarya Rai and taken from a 1917 novel that’s reportedly been filmed nine times in four Indian languages, “Devdas” is a soap opera story of true love thwarted by indecision, scheming women and family pride. With its opulent production design, gorgeous costumes and elaborate choreography, this is the kind of spectacular fairy tale musical no one else is making anymore.

Of the English-language films at Cannes, two of the most involving were a pair of British films, “Tomorrow La Scala!,” in the Un Certain Regard section, and “Morvern Callar” in the Director’s Fortnight (another Fortnight film, France’s “Bord de Mer,” won the Camera d’Or with special mention for the Mexican film “Japon”).

The first dramatic film by documentarian Francesa Joseph (who wrote it as well), “La Scala!” shows what happens when the ambitious director of an opera troupe (hence the title) mounts a production of Stephen Sondheim’s “Sweeney Todd” in a maximum security prison and uses lifers in the chorus. Though what transpires is predictable in broad outline, the film’s cheeky verve and tangible edge of dark reality make it a most pleasant surprise.

“Morvern Callar,” the second film by Lynne Ramsay, is a strong follow-up to her widely admired “Ratcatcher.” It stars Samantha Morton as the 21-year-old title character who has to put her life back together when her boyfriend commits suicide in their apartment at the height of the Christmas season. Like “Ratcatcher,” “Morvern” displays Ramsay’s ability to use the power of images to take her characters on emotional and psychological journeys. “Morvern Callar” did well at Cannes, winning both the Prix CICAE, given to the best film in the Fortnight, and the Prix de la Jeunesse, voted on by a group of young French cinephiles, but it’s likely the director will remember this festival for something else entirely.

According to Daily Variety, Ramsay “got hitched at an impromptu ceremony on an old yacht” that sailed 12 miles into international waters to give the captain the proper authority. “It was emotional and surreal,” Jim Wilson, the deputy head of production at FilmFour, who gave the bride away, told Variety. “It was the best production I saw in Cannes--apart from our own films, of course.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.