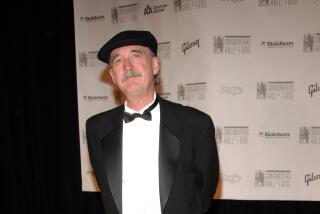

Waylon Jennings, 64; Country’s ‘Outlaw’

Waylon Jennings, the black-clad singer who personified country music’s 1970s “outlaw” movement, died Wednesday from complications of diabetes. He was 64.

Jennings, who had struggled with diabetes-related health problems in recent years--he had a foot amputated last year--died peacefully at his Arizona home, according to his spokeswoman, Schatzi Hageman.

Jennings’ chief legacy rests with his role in liberating country music from Nashville’s conventions.

Teaming in the ‘70s with the like-minded Willie Nelson, he broke ranks with the country establishment’s conservative sound and lifestyle, bringing a rock edge to the music and a freewheeling approach to his lifestyle (he would struggle for years with a cocaine habit, finally kicking it in 1984).

Sometimes sporting a buccaneer’s beard and looking like a biker in black leather, he and the long-haired Nelson teamed on such records as “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys” and “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love),” forging an unlikely alliance between the era’s hippies and honky-tonkers.

“He was a dear friend, one of the very best, of 35 years. I will miss him immensely,” Johnny Cash said Wednesday in a statement from his home in Jamaica.

“Waylon and I were real close,” said Merle Haggard, another country maverick who was born in the same year, 1937. “We were close in age, and we both made our start out West. Sometimes I was mistaken for Waylon and sometimes he was mistaken for me throughout our careers. We go back a long way. We’re all going to miss him--he’s one of a kind.”

Born in Littlefield, Texas, the son of a guitar-playing truck driver, Jennings picked cotton as a youngster and saw music as a way out of his family’s poverty. A fan of such classic country figures as Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb and Jimmie Rodgers, he got a job as a radio disc jockey at age 12 and soon began playing at talent shows.

He moved to Lubbock in 1958, where he met rock singer Buddy Holly. Holly produced Jennings’ first single, “Jole Blon,” and Jennings became the bassist in Holly’s band. On the night of the 1959 plane crash that killed Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper), Jennings gave up his seat on the plane to Richardson.

Jennings moved to Phoenix and formed a band that began drawing crowds--and talent scouts--at J.D.’s nightclub. After Jennings’ brief affiliation with Herb Alpert’s L.A.-based A&M; Records, Chet Atkins signed him to RCA, and he moved to Nashville. Rooming with Cash, he soon established himself as a rowdy character and a hit-making singer, scoring seven Top 10 country hits by the end of the decade.

“I was stunned the first time I heard him singing a demo of Harlan Howard’s ‘Green River,’” singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson said Wednesday. “I was a janitor at the studio at the time. I became a fan for life, thrilled by the passion and intensity of his voice.”

But Jennings became increasingly disillusioned by the slick, strings-saturated sound of mainstream country music, and during a severe bout with hepatitis he considered leaving the business. But after changing managers and taking control of his own recordings in the early ‘70s, Jennings was on a new track.

Collaborating with Jack Clement and Tompall Glaser, Jennings constructed a leaner, stripped-down sound and recorded songs by such young writers as Kristofferson, Billy Joe Shaver and Mickey Newbury. Nelson co-produced the 1974 album “This Time,” which included four Nelson songs.

The 1976 collection “Wanted: The Outlaws,” featuring separate cuts by Jennings, his wife Jessi Colter, Nelson and Glaser, was the first country album to be certified platinum (sales of 1 million). He had a No. 1 country record (and his highest-charting pop hit) in 1979 with the theme from the TV series “The Dukes of Hazzard,” for which he also did the narration.

Like many country veterans, Jennings was discarded by Nashville in the 1990s as a new generation of pop-leaning artists dominated country radio. In that period, he toured and recorded with Kristofferson, Nelson and Cash as the Highwaymen. His last album, “Never Say Die,” came out in 2000.

In all, Jennings sold more than 40 million records worldwide, according to his representatives. He had 53 Top 10 country hits, 16 of them No. 1. He won two Grammys and four Country Music Assn. Awards.

Despite his success, Jennings was reticent about such honors. He skipped his induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame last year, saying it meant “absolutely nothing, if you want to know the truth.”

“Waylon Jennings was an American archetype, the bad guy with the big heart,” said Kristofferson. “When I introduced him to Muhammad Ali, they were like two little kids delighted with each other. What they had in common was being so openhearted to everyone.

“Over the years, I got to work by his side and be his friend and hear him say some of the funniest lines I’ve ever heard. Right now he’s probably whispering in Johnny Cash’s ear, ‘See, I told you I was sicker than you.’”

Jennings is survived by Colter, his fourth wife, and seven children.

*

Times staff writers Geoff Boucher and Randy Lewis contributed to this story.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.