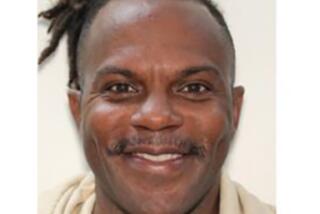

John Thomas, 71; Member of Venice Beats

Even among the bohemians of Venice, John Thomas stood out. He was 6 feet 4, weighed 300 pounds and spoke in a rolling, resonant baritone that left no one behind.

But, more than that, he was a poet--”the best unread poet in America,” according to Charles Bukowski, the infamous bard of lowlife Los Angeles who knew Thomas for 30 years.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. July 18, 2002 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Thursday July 18, 2002 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 9 inches; 331 words Type of Material: Correction

Poet’s obituary--An obituary of Venice beat poet John Thomas in the April 7 California section incorrectly stated that he died at the Veterans Administration hospital in Westwood. He had been treated there earlier, but died at County-USC Medical Center. The obituary also omitted some important facts that came to light after publication of the story. At the time of his death on March 29 at age 71, Thomas was serving a 120-day jail sentence after he pleaded no contest to a charge of sexually molesting his daughter in 1971 when she was 14. His sentence included 60 months of probation, and he was ordered to pay $200 in restitution. A change in state law lifting the statute of limitations on unreported sex-abuse crimes in which the victim was a child allowed him to be prosecuted.

*

For The Record

Los Angeles Times Sunday July 21, 2002 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 2 inches; 101 words Type of Material: Correction

Thomas obituary--A correction in Thursday’s Times regarding the April 7 obituary on Venice beat poet John Thomas misstated the charge that led to his 120-day jail term. It said he pleaded no contest to a charge of sexually molesting his daughter when she was 14. In fact, the charge that led to his jailing was one count of sexual contact with a 15-year-old.

Gadfly, poetic realist and magnificent reader of his own work, much of which is out of print or unpublished, Thomas was a commanding figure on Los Angeles’ avant-garde scene for four decades.

“He was by far the greatest underground poet in Los Angeles for the last 35, 40 years,” poet and Bukowski biographer Neeli Cherkovski said of Thomas, who died March 29 at the Veterans Administration hospital in Westwood.

The cause of death was congestive heart failure, said Thomas’ wife, poet Philomene Long. He was 71.

“He was the sage of Venice,” said Fred Dewey, director of Beyond Baroque, the Venice literary arts center that planned an evening of readings and tributes to Thomas last night. Thomas was revered by many for his grace and clarity in works such as “From Patagonia,” a lengthy poem about Los Angeles written in the form of a diary. His major collections include “Epopoeia and the Decay of Satire,” “Abandoned Latitudes” and “John Thomas,” all published in the 1970s and early 1980s.

He also was an early member of the Venice beats, a group that historian John Arthur Maynard, in his 1991 book on the subject, called “an outlaw strain in Southern California letters.”

Thomas fit easily into the mold.

Overlooked in most accounts of the beat movement made famous by Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and other writers, the Venice beats were literary outsiders who shunned celebrity for lives based on art and poverty.

While the beats of San Francisco’s North Beach and New York City’s Greenwich Village aspired to transform society, the Venice beats “knew the people better than that,” Maynard wrote in “Venice West, the Beat Generation in Southern California.”

“What they really wanted to do,” Maynard said, “was to write their poems, paint their paintings, take their drugs, love their friends and keep from getting busted by the police.”

When he was nearing midlife, Thomas abandoned his job and family in Baltimore and thumbed his way west. He landed in Venice, surrounded by artistic misfits of one kind or another, who were joined by their rejection of popular culture and their passion for literature and life on the seamy edge. They labored in obscurity and, if you believed them, preferred it that way.

“John was the most un-Hollywood writer in Los Angeles,” said Cherkovski. “He didn’t want to teach in a university. He had once been in the business world and dropped out. He had ‘tuned in, turned on and dropped out,’” he said, citing what became the credo of youth in the ‘60s, “but he did it in the 1950s.”

Born John Thomas Idlet, he grew up in Baltimore, the son of a teacher with an overbearingly critical manner and an ice cream factory foreman who claimed to have invented the double cone.

He attended Baltimore’s Loyola College and briefly considered the priesthood, until the Korean War intervened. With an IQ of 180, he was deemed highly suited for decoding work and became a cryptographer in the Air Force.

After his discharge in 1953, he returned home, married the first of four wives and got a job as a computer programmer for Univac.

The turning point came when he was hit by a truck and broke his ankle. Laid up for weeks, he grew a beard and began to write. He produced three novels, none publishable.

Then he read “The Holy Barbarians,” a 1959 guidebook to the unfolding beat scene in Venice written by Lawrence Lipton, a poet, author and impresario of Venice West.

Thomas later told Maynard, the historian, that he found the book “silly.” Nonetheless, he left home with $14 in his pocket and hitched a ride across the country, intending to reach San Francisco.

But his ride ended in Los Angeles, so he took a bus to Venice. He called himself a poet and, exposed to practitioners such as Stuart Perkoff, began to write like one.

To support himself, he became manager and cook at the Gas House, Lipton’s bohemian hangout and club near the Venice speedway. Buying food with the meager donations of tourists, he was necessarily resourceful, scrounging “trash fish” like bonito and barracuda for chowder and finding amazing bargains on “filet mignon,” actually horsemeat from a nearby pet store.

After a brief period in San Francisco, Thomas moved east in Los Angeles, living in ramshackle apartments and houses around Echo Park and Silver Lake that were cluttered with papers, books, bottles, a worn typewriter and his collection of 100 pipes. Unread books, some in rotting packages from mail-order houses, lined his driveway.

Poet Wanda Coleman met him at his Silver Lake abode in 1966 when she was visiting a brother who lived downstairs.

“John Thomas,” she said with affection, “was my first mentor.” If Coleman’s brother wasn’t home, Thomas would invite her in for tea and hours of rambling discussion about literature and L.A.’s underground culture. He told her about cult figures such as satirist Lenny Bruce, whom he knew.

And he shared the adventures of the larger-than-life Bukowski, whose antics inspired the 1987 film “Barfly.”

Bukowski would visit Thomas after working the graveyard shift as a mail sorter at Terminal Annex.

Although Bukowski eventually willed himself out of obscurity and published far more widely than Thomas, Thomas was “one of the few persons who could intimidate Bukowski even before Bukowski came into the room,” Cherkovski recalled. Bukowski died in 1994.

Extremely well read, Thomas was an exacting wordsmith who was rarely averse to pointing out the fallacies he saw in other poets’ work.

“John was ruthless in that, and often very unpopular because of it,” said Paul Vangelisti, a poet who also was Thomas’ editor. “He was an exceptionally fine writer.”

He did not write poems for more than a decade, however. A person who could spend hours in silence “listening to the trees,” he devoted most of the 1970s and early ‘80s to writing in a private journal.

He published little over the last 20 years, a fact that Bukowski noted in one of many kind poems he wrote about Thomas. In “Big John of Echo Park,” published in 1988, Bukowski said of his friend:

It’s a

good thing

for many of us

in this stinking

racket

that he just

doesn’t like to

type

too much

Thomas offered a cold-eyed assessment of himself in “Patagonia,” the long prose piece published in 1983:

Most writers would regard Southern California as banishment enough. To live in Los Angeles, a minor poet of some local repute: surely this satisfies any interpretation of the Doctrine of Sufficient Disgrace. Well, for me, nothing has ever proved Sufficient. The Fatal Flaw, amigo.

“To me it’s a tragedy so much of his work is out of print or [never] published,” said Dewey of Beyond Baroque.

In an effort to bring Thomas to a wider audience, the literary center is selling a CD of poems he wrote for Long and accepting donations to the John Thomas Fund, payable to Beyond Baroque. Some of the money also will be used to help cover funeral costs.

One poem that may be long remembered is engraved in a concrete wall on the Venice boardwalk. It is called “The Ghosts of the Poets”:

Even the barrel of my pen

is full of the ghosts of uncouth poets.

In case you wondered,

they are the wild kidney. They are

the bitter crackling sound I hear

when Philomene brushes her hair.

In case you wondered,

they are the small transparent parasols

all of us stroll beneath.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.