Fashion designer Rudi Gernreich defied haute-couture rules with socially aware clothes that said ...

PHILADELPHIA — Now that the Sept. 11 attacks have made the materialistic, celebrity-fueled fashion scene seem all the more frivolous, it could be time for another Rudi Gernreich moment. The Austrian-born designer, who died in Los Angeles in 1985, is perhaps best known for creating sensational pieces such as the topless bathing suit and the thong. But he was more than a 1960s-era agent provocateur. He was a designer guided by a social conscience, which makes the current reexamination of his work at the Institute of Contemporary Art here seem all the more relevant.

“I’m totally unconcerned with skirt lengths,” he told Woman’s World magazine in 1966. “They are not the issue. The issue is flying to the moon, killing men in Vietnam, teenagers pouring kerosene over Bowery drifters and setting them on fire. Life isn’t pretty. Clothes can’t be pretty little things.”

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Sept. 29, 2001 FOR THE RECORD

Los Angeles Times Saturday September 29, 2001 Home Edition Part A Part A Page 2 A2 Desk 1 inches; 26 words Type of Material: Correction

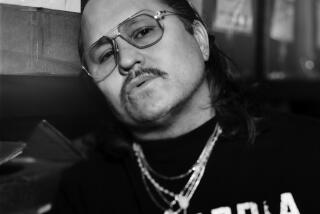

Wrong photo credit--A photograph in Friday’s Southern California Living section was mistakenly credited to Fahey/Klein Gallery instead of to the photographer, William Claxton.

He defied the rigid traditions of Parisian haute couture, crafting democratic-minded innovations that define dressing to this day. But his influence goes well beyond fashion, giving him a place in the history of American design alongside the likes of Charles and Ray Eames. To him, fashion didn’t have to be just frippery; it could be an instrument for social change, according to longtime Gernreich collaborator Layne Nielson, who is writing a biography about the designer.

The exhibition’s title, “Rudi Gernreich: Fashion Will Go Out of Fashion,” is taken from a 1970 Life magazine interview in which the designer predicted a time when “people will stop bothering about romance in their clothes. Fashion will go out of fashion. The utility principle will allow us to take our minds off how we look and concentrate on what really matters.”

Throughout his career, Gernreich was influenced by social concerns ranging from his Socialist family background to his founding role in the Mattachine Society in L.A., a forerunner to today’s gay movement. “He did what all truly innovative designers do, which was to tap into what was going on at the time,” said Louise Coffey-Webb, curator of the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising in L.A., which loaned many pieces from its archives for use in the Philadelphia show.

Born in Vienna in 1922, Gernreich, son of a hosiery manufacturer, was forced to flee the city in 1938, six months after the Nazi invasion, according to Nielson. He was 16 when he and his mother joined a wave of Jewish refugees immigrating to Los Angeles.

During the 1940s, he was a dancer and costume designer for the politically progressive Lester Horton Modern Dance Troupe (an experience that undoubtedly influenced many of his body-conscious designs). By the mid-1940s, he was supplementing his dance career designing fabrics for Hoffman California Fabrics, and in 1952, with the help of fellow Viennese immigrant Walter Bass, he introduced his first full-scale clothing line of loose-cut dresses.

In the 1950s, when most designers were mimicking Christian Dior’s New Look (nipped feminine waists, full skirts, torpedo bras and corseting), Gernreich was emancipating the female body, taking the boning out of swimsuits and introducing the first knit tube dresses, according to show curator Brigitte Felderer, who first mounted the exhibit of 125 looks last year at the Neue Galerie in Graz, Austria. He turned heads with shocking shades of orange and red and used cutouts and sheer fabrics long before Gucci’s Tom Ford.

Gernreich, along with Bonnie Cashin, was one of the first designers to use hardware (zippers, springs, metal fasteners) for ornamentation. He was the first to use clear vinyl in clothing, creating what Coffey-Webb considers to be his signature look: the bright-colored, wool knit miniskirt with clear vinyl panels.

Although attempts had been made at creating unisex clothing earlier in the 20th century, they did not succeed. The tanned and toupeed Gernreich, a consummate showman, was able to make the look a fashion statement, dressing male and female models identically for a 1978 Life magazine fashion spread. In 1979, he patented the first thong. Nielson summed it up best: “He is the source of most of what people are wearing today.”

Although Gernreich enjoyed the trappings of fame (he hired a publicist with his first royalty check), he didn’t particularly care about selling symbols of prestige, according to Felderer. In the 1970s, when logo scarves were all the rage, Gernreich--who was largely unaffected by trends--decorated his scarves with jumbled letters instead. He maintained the belief that clothes should be accessible and reasonably priced (although his certainly weren’t cheap).

One of the first to embrace the concept of lifestyle marketing, he introduced the widely copied “total look” with undergarments, colored tights, shoes and bags to match. He also dabbled in home furnishings, perfume and, after his fashion career fizzled out in the 1980s, gourmet soups.

“He basically invented every modern style idea,” said Cameron Silver, owner of Melrose Avenue vintage store Decades. “To a large degree, he’s underappreciated.” (There are no plans currently to bring the exhibit, which runs through Nov. 11, to L.A.)

Like many in the art community, Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art director Claudia Gould is leery of fashion finding its way into museums. But she maintains Gernreich stands apart from the recent Jacqueline Kennedy exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Giorgio Armani show at the Guggenheim. Jackie wasn’t an artist at all, but a personality, and Armani was a master tailor who happened to have the money to fund a good part of his own exhibit. But Gernreich is different, she said: “He transcended fashion.”

Just four days after the terrorist attacks, the Philadelphia exhibition opened as scheduled with a gala for about 1,000. “We thought about postponing, but we didn’t want to,” Gould said. “In a way, it was very cathartic.” Attendance since then has been good, she said.

To see Gernreich’s clothes is to understand how designers, like artists, can reflect social and political unrest. In the 1960s, “His clothes were democratic mediums of equality between men and women, young and old, rich and poor,” Felderer said. But his most revolutionary piece, the topless “monokini,” introduced in 1964, was largely misunderstood by the public, according to model and muse Peggy Moffitt, who wrote “The Rudi Gernreich Book” (Taschen, 1999).

“He wanted it to be a statement about freedom and equality and the smarmy ‘tee-hee’ attitude toward women and their breasts that existed particularly in America. At the time, women with cleavage were being used to sell everything from motor oil to refrigerators,” she said. Originally, the piece wasn’t going to be manufactured, but the moment it was, “Every crazy woman who wanted to be arrested bought one and photographers from sleazy magazines had a field day. The reaction made [Gernreich] wince,” she said.

When his notoriety landed him on the cover of Time in 1967, Gernreich began to feel the intense pressure which all successful designers labor under. In a continual effort to top himself, his creations became more and more outrageous, threatening to eclipse his raw talent. Increasingly, his clothing had less to do with social issues and more to do with theatricality, Nielson said.

The costumey collection of June 1968, replete with thigh-high boots, tweed tutus and oversized turbans, collided with the nation’s somber mood. During that troubled year, the North Vietnamese Tet offensive and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had “exposed American vulnerability,” Nielson said. “The fashion press had had enough. It’s very similar to what’s happening today. People were saying, ‘This is enough frivolity.”’

But even Gernreich’s folly had social value because it forced “the first serious dialogue about the relevance of fashion, fantasy fashion in particular, in a time of social stress,” Nielson said. After 1968, Gernreich would present only a few more collections, many of which simply revisited old themes.

In 1970, the shootings at Kent State University inspired the designer to resurrect his earlier military look (a Gernreich original). The “Back to School” collection, as he called it, was shown by models toting real guns. “He was making a statement. The idea of sumptuous dressing when students were being shot seemed to have no bearing on reality,” Moffitt said. She believes the recent terrorist attacks would have inspired Gernreich to create a similar collection. “Rudi’s are the clothes that are still relevant today. And we might just have to wear them with guns again.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.