A Tie That Binds Jews and a Special Family

William Bingham, 47, is a Connecticut Yankee whose forebears came over on the Mayflower with their Christian piety and family fortunes. His grandfather, Hiram Bingham III, was the rollicking adventurer on whom the fictional character of Indiana Jones was based. His father, Hiram Bingham IV, attended Groton, Yale and Harvard and then entered the U.S. diplomatic corps.

By the time William was born, however, his dad had mysteriously and prematurely resigned from the diplomatic life. He had settled with his wife and 11 children in a pre-revolutionary house on a lush Connecticut farm that had been in the Bingham family for generations.

It might seem there would be little connection between this WASP Connecticut family and a congregation of 1,000 Jews, mostly in the entertainment industry, who will celebrate the high holy day of Yom Kippur today at a former movie house on Wilshire Boulevard, using new prayer books featuring brilliant reproductions of Marc Chagall’s biblical art.

But what binds these elements together--the Connecticut Binghams, the California congregation and the European artist Chagall--is the one thing we have found to celebrate in this country since Sept. 11. Heroism, a trait that runs long and deep through American history, is what William Bingham only recently discovered was the great legacy left to him by his rather secretive father.

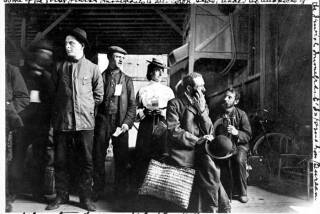

It turns out that Hiram Bingham IV hadn’t failed in life at all. In fact, he was a hero who succeeded admirably at his chosen career: secretly saving lives. As a vice consul in charge of visas, living at a villa in the south of France, he helped many hundreds who had been marked by the Nazis for internment and extinction to survive.

Some whom he helped were Jewish. Others were not but were artists whose work was considered by the Nazis to be “decadent and corrupt.” Still others had both strikes against them. Marc Chagall was one of those.

Although he was already famous, considered one of the great modern artists of the era, Chagall had been arrested by the Nazis and then released with Bingham’s help. He knew he was on the list for extinction, that the next step for him was a concentration camp. Reluctantly, he and his wife fled their beloved city of Paris for the sanctuary of the diplomat’s villa. They hid there until Bingham, working with the Resistance movement, managed to engineer their safe escape.

There were dozens of famous writers, musicians and artists who fled Paris around the same time--among them Fernand Leger and Salvador Dali. And helping people to escape apparently was not part of the plan of the U.S. diplomatic corps, William Bingham says. His father was repeatedly asked by his superiors in the State Department to stop helping doomed citizens to flee their fate.

“My father was very deeply involved by then. He had joined with this international group who went on to become the underground, the French Resistance movement. They smuggled people out over the French Pyrenees and in to Spain. The Nazis found out and complained to Washington. Washington ordered my father to stop. He defied the order for months, until he was removed from his post and transferred to Latin America.” By the time he left, though, he and the network had helped at least 1,000 people get out.

From then on, Bingham was relegated to what his son calls “a succession of meaningless, low-level, unimportant desk jobs” where he could not get involved with the war. They were jobs that tried his patience and his soul. He was deliberately denied promotions for years, his son says, by superiors who said his attempts to rescue people had been “inimical to the interests of the United States, and who said it would be embarrassing if it was ever found out that an American diplomat had helped to break laws--even another country’s laws.”

Near the end of the war, even from the isolated posts in which he served, he had discovered that the Nazis were smuggling war criminals, stolen art and other assets in submarines from Europe to Argentina. Incensed that they were succeeding, he reported the facts repeatedly to Washington, telling officials how to intercept the criminals and the stolen goods. Over and over again, he got no response, according to his son.

He resigned in protest--and in frustration. He spent the rest of his life as a philosopher and artist, his son says, keeping quiet about his secret career. When he died at 84 in 1988, he was almost penniless, having spent all that was left of the family money to raise and educate his kids and to keep the family farm afloat.

William and his 10 siblings grew up knowing little about any of this. By the time the children were old enough to press their father for facts, they saw that he was not about to ever tell them anything. When he died, he took his secrets with him.

Five years ago, William Bingham discovered a secret cupboard behind a fireplace in the home that was his parents’ and where he now lives with his wife and children. Inside were World War II-era folders packed with his father’s coded notes, scribblings, personal journals--records of meetings with refugees and members of the underground. He found letters from Chagall and others, thanking his father for saving them, along with photos and lists of refugees. He discovered documents chronicling his father’s attempts to do the right thing despite his superiors’ attempts to stymie him. He even found letters from his father’s alleged friends--anti-Semitic ramblings asking his father why he would want to ruin his life and career for ... them.

Bingham even found artwork by Chagall. One drawing, done on a page of Le Matin newspaper, was Chagall’s tiny pictures of the artwork in his apartment that he wanted to have someone remove and save for him after he fled.

It was a treasure trove--and one which Bingham is certain that his father wanted him to find. “He wouldn’t have made sure to preserve it all those years if that hadn’t been the case,” he says.

Bingham, an attorney, took his materials to Holocaust experts. Rabbi David Baron, spiritual leader of Temple Shalom for the Arts in Beverly Hills, was one. A specialist in the study of Holocaust heroism and son of a Holocaust survivor himself, Baron says the names of that era’s villains have long been known. He was starting research on the era’s heroes when Bingham’s papers came to light.

“I was fascinated. He saved so many regular people and so many of the world’s great minds. Talents like Chagall, and Nobel prize winner Otto Meyerhoff, a scientist, and authors Lion Feuchtwanger and Franz Werfel, who went on to write ‘The Song of Bernadette.’ He saved Thomas Mann’s brother and composer Gustav Mahler’s widow,” Baron said. “And he had to go against his own government’s policies in order to do this. He sacrificed his career--he was right on track to be an ambassador. And then he had to keep it secret all his life.”

Hiram Bingham is not unknown anymore. He was featured in last year’s History Channel documentary, “Diplomats for the Damned,” which Baron co-produced. He was included in a 1999 U.N. exhibit, “Visas for Life,” which is now on tour. And he will be the subject of an upcoming KCET show, for which his son is being interviewed in Los Angeles this week.

Baron has designed a book of prayers and meditations for his congregants, featuring 31 images of Chagall’s biblical art, along with a letter from the artist thanking Bingham for saving him. Three years in the making, the limited-edition volume has just been published and will be used for the first time at services this week. To further honor the man who saved so many, the rabbi invited William Bingham to speak about his father’s righteous deeds at Yom Kippur services in the temple. Bingham was delighted at the idea.

“My father believed that you are put here by God to do good works. He could not turn his back on his beliefs or on the people who needed him. Just think, if my father hadn’t done what he did, Chagall and many others would not have lived to produce the great works they did.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.