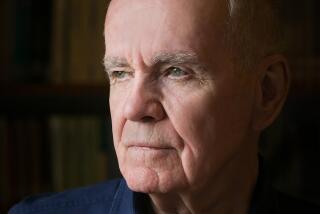

Patrick O’Brian; British Master of the High-Seas Adventure Novel

The graceful and contrarian British novelist Patrick O’Brian, who surprised the literary world--and himself--by luring legions of readers away from the onslaught of the Information Age and back to the slower epoch of sailing ships and discovery, has died.

A pathfinder who defied trend by resurrecting the long-ago form of the serial novel, O’Brian turned 85 just a month ago. His London agent and New York publisher said the writer took ill in Dublin on Saturday and died Sunday in a hospital. In accord with his wishes, no announcement of his death was made, pending the return of his body to his longtime home in France for burial.

O’Brian’s quiet country life and his remarkable books turned a shoulder to the scatter and commercialism of modern society. Retreat to the past, he beckoned. With a precise and fertile imagination, he provided readers with sanctuary in the improbable world of high-seas adventure in the British Royal Navy of the early 1800s.

His Aubrey-Maturin series of 20 books was gauged by critics in the United States and Britain as some of the finest historical fiction ever. It might be admitted that the books also had elements of the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew for well-read grown-ups.

Although frail, O’Brian had disclosed recently that he had completed three chapters of Volume 21. A friend said he was busy writing until his final weekend.

Fans who otherwise had no interest in the British battles with Napoleon were swept with rare intensity into the arcane realm of men-of-war, dinners of soused pig’s face, the roar of evening cannon practice, sunsets aloft in a cloud of square-rigged sail, and nighttime string duets with Capt. Jack Aubrey on the violin and surgeon Stephen Maturin on the cello as the moon shimmered over strange oceans long ago.

One of the most formidable friendships in English literature, the duo had kinship with the likes of Sherlock Holmes and Watson, with “Lucky Jack” Aubrey the fearless and good-natured English warrior who often lost his footing ashore, and the lovelorn, unkempt Maturin, a moody and complex Irish-Catalan naturalist, medical doctor, intelligence agent and friend--and, it should be added, a personality drawn from the author’s own.

Readers Felt a Bond to Characters

Those who mourn O’Brian’s passing now grieve the loss of characters whose lives they followed in intimate detail for years, through romance, marriage, moral dilemma, storm, shipwreck, adventure and any number of fortunes and misfortunes.

To read O’Brian’s seafaring tales is to be invited into a club. A nod from one O’Brian reader upon the acquaintance of another says, literally, volumes. Just the mention of a character like Diana conjures a whole life of elegance, mystery, longing and frustration.

Some followers went farther, and in recent years publishers fed the O’Brian craze with supplemental titles that explained the lexicon and geography and food of his novels--parenthetical details that he wasted little ink elucidating himself. CDs were recorded so that readers could enjoy the music of the time.

Although his genre would ordinarily appeal to men, O’Brian’s elegance as a storyteller, his unhurried explorations into the nuances of life at the dawn of a new century nearly 200 years ago, plus his flowing exactness with mood and place attracted an equally steadfast following of women. Entire books in the series passed without a single naval battle, usually the staple of this kind of fiction. His own favorite writer was Jane Austen.

One New Jersey woman wrote O’Brian and said she named her son Jack after the captain and would have picked Aubrey for a girl.

In one of the last interviews of his life, O’Brian told The Times in November that he was feeling “quite ancient, you know.” But he playfully agreed to divulge his secrets of writing:

“May I start at the beginning? I take a blank sheet of paper and I take a pen and I write Page 1. And I go on to about Page 365, and at that point I write, ‘The End,’ ” he said, grinning.

Asked in 1998 to guess why more serious writers did not employ history as a backdrop for their stories, O’Brian replied: “I think probably you have to be terribly good to bring it off.”

Writing slowly in his one-bedroom vineyard overlooking the sea in southern France, and then, after the death of his second wife, Mary, in 1998, working in a room at Trinity College in Dublin, O’Brian created stories that crackled with the tension and forward motion of the best of contemporary action novels.

Bringing a Long-Past Era Back to Life

But, with his near perfect re-creation of period language and perceptions, readers enjoyed the soothing, and illuminating, perspective of life as it unwound at a less bewildering pace--when a letter might not be delivered for six months so one had time to compose it properly, and when an insult was judged not by the size of its exclamation point but by how carefully it was composed to resemble a flowery compliment with a razor blade buried in the tail end.

When the author came to prominence, his face was already deeply lined with age. He was an inspiration for those who hoped that their greatest success would arise later in life. He began the Aubrey-Maturin series in 1969 with “ Master and Commander” at the age of 54. Twenty years later, the books were still virtually unknown in America.

First attempts to publish the series in the United States fizzled. Then Starling Lawrence, editor in chief of W.W. Norton & Co., heard about the writer by word of mouth and began lovingly issuing the volumes in 1990. The next year, when O’Brian was 76, a review in the New York Times called his work “the best historical novels ever written.”

“Unique is certainly close to the mark,” Lawrence said of the writer, who became his close friend. “I have been asked to make comparisons, but there are no useful comparisons to be made; his work, its structure, is very old fashioned, and it contains the elements that deserve to be called great literature.”

By the end of the decade, O’Brian was on the best-seller lists with worldwide sales exceeding 3 million. The last of his visits to the United States occurred in November, when O’Brian came to New York and hobnobbed at the New York Yacht Club with the likes of Walter Cronkite and William F. Buckley Jr. He was standoffish about fame, however. To hear him tell it, what he enjoyed most about the trip was going to the Central Park Zoo to see polar bears and penguins.

He insisted that his own life was unimportant compared to his work. Few of his fans listened, of course. And he surely knew better. Earlier in his career, he wrote a well-received book called “Picasso: A Biography,” and thus understood that artists, when they achieve renown, are likely to become as absorbing as their art.

In 1998, O’Brian fans were delighted to learn that the author’s fertile imagination had created a fiction of his own life. He had always been parsimonious in what he revealed of himself, leading people to believe he was a bookish Irish Catholic who married, moved to Wales and then to rural France. He served in World War II as an ambulance driver during the blitz and in some unspecified capacity for British intelligence.

Those who dug into his past found he was actually born in London as Richard Patrick Russ and raised a Protestant. He had a previous marriage, two children and a three well-reviewed books of fiction. In 1945, for reasons never fully explained, he remade himself into Patrick O’Brian and started his literary life anew.

His biographer, Dean King, author of the forthcoming book “Patrick O’Brian: A Life Revealed,” to be published by Henry Holt, said the writer walked away from his first marriage and a grievously ill child and then, feeling guilty, set about “putting the past behind him.” King said the author is survived by a son with whom he had not spoken in 31 years.

King said O’Brian’s achievement was a “great example of the artistic. He gave us some of the most profound writing ever about love and friendship. Yet, in life, he did not have great quantities of either.”

In addition to the Aubrey-Maturin series and his Picasso book, O’Brian wrote a biography of 18th century botanist Joseph Banks, other novels, a book of stories and an account of shipboard life in Lord Nelson’s navy. He also was a prolific translator.

Two of O’Brian’s early works, originally written under the name Richard Russ, are to be republished in April: “Caesar,” the author’s first work, a short, fantastical story of natural history written when O’Brian was 14 and published when he was 16, and “ Hussein,” a picaresque, Kipling-like adventure story set in India during the British colonial era.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.