What Ever Happened to Hip?

We’ve lived with it for so long, it’s difficult to say when the reversal began. When Coca-Cola sent a replica of Ken Kesey’s party bus on the road to promote Fruitopia? When the Gap decided that a bored sneer was the ultimate American look? When Joe Camel first donned a zoot suit and shades to hang with his jazz-scribbling, joe-swilling buddies?

Or perhaps it was more recently, when William Shatner stood Beatnik-lonely in front of a mike in a smoky room reciting bastardized lyrics to the Animals’ “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” to promote Priceline.com.

That commercial says it all, demanding that we get out of this place to a world of four-star hotels and swanky restaurants, a world we can enter through money and the Internet. But, it hastens to add, we can do this and still be hip, because Shatner is being ironic, see, and irony is the ultimate hallmark of hip, ergo William Shatner is hip and if William Shatner can be hip, well then anyone can.

And we all want to be hip, right?

During the last 40 years, Americans have watched as hip moved from a suspicious-looking counterculture to a consumer-driven mandate. It has become our national currency, our social deity. Everyone from Tina Brown to Target wants to be hip. At clothing companies, car companies, cola companies, coffee companies, dot-coms and, of course, in nearly every conceivable publication, the directive is constant and inarguable--get hip, stay hip and then get hipper. Hip sells. And, more important, hip buys.

Of course, there is a problem here, or at least a dilemma. Hip, by historical definition, is a version of life that defies the mainstream, defines the American rebel. That’s why we like it. So anything that shows up at the galleria or on TV, or even on the cover of Rolling Stone is not hip. Mass production is what hip rebels against--mass production, man, is square.

“We all want to be young, we all want to be unique and cutting edge, and hip has become a short-hand for that,” says David Ulin, an L.A. journalist who has written extensively about the Beats. “But most of us don’t have time to be true iconoclasts, so we settle for a look, for a style, for buying iconoclastic.”

Yet given all the goals we, as a society, could have, we choose hipness. Why not wisdom? Or serenity? Or usefulness? Even sophistication seems a bit more, well, adult.

Hip, we seem to forget, is more than a synonym for trendy or new. It is a legitimate documentable counterculture, the product of post-World War I alienation and urban modernism, the fraternal twin of jazz.

The original hipsters were the hepcats, young black men living in Harlem in the 1930s, whose lives revolved around bebop. They spoke in slang and dressed sharp, slicked their hair back and smoked marijuana, then the ultimate demarcation between hep and square. After World War II, marijuana gave way to heroin and hep became hip, an oblique homage to opium smokers of the previous century who got their high horizontally, lying “on the hip.”

From Bebop Jazzmen to White Intellectuals

By the late 1940s, hipsters could be found in every city, in every color, as Allen Ginsberg observed, “dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix/angelheaded hipsters burning for the heavenly connection . . .”

Intentionally or not, Ginsberg brought the term “hip” into the vernacular of the intellectual middle class, where it was nailed to the floor a few months later by then-angry-young-novelist Norman Mailer in his windy dissertation on hip titled “The White Negro,” which appeared in the journal Dissent. After Jack Kerouac published “On the Road,” marrying the hipster tradition with the predominantly white Beat subculture, what had been an urban counterculture of the racially and economically disenfranchised found its way into the hearts and minds of disaffected suburban youth.

Although always self-conscious about its appearance, hip remained risky, dangerous, angry and genuinely displaced from the mainstream. It was not something parents handed their children credit cards to buy. It was inextricably bound to the drug culture, as the body count attests: Charlie Parker, William Burroughs, Lenny Bruce and, later, Hendrix, Joplin, Morrison, Belushi, Cobain--the truly hip often died young, broke and by overdose. And those who survived, or thrived, did so in an atmosphere of constant youthful insouciance--late nights, missed rent, hangovers and withdrawals, social rejection and often questionable personal hygiene.

When the children of the baby boom came of age and embraced the hip sensibility, morphing it into various political and social spinoff movements, it was only a matter of time before the counterculture became the culture. In the ‘80s, the hippies turned into yuppies with jobs and stock options, but also with a perpetual desire to know what was the next hip thing so that they could get it too, in the luxe package, of course.

An entirely new youth market, Gen-Xers, came of age only to discover that no one was going to leave them alone long enough to afford them the chance to produce a legitimate counterculture--even punk couldn’t stay underground for long. Marketers hovered around neighborhood dives, counting tattoos and tongue piercings, eager to supply whatever these disaffected hearts desired.

“One of the aspects of hip that you hear tossed around is ‘authenticity,’ ” says Thomas Frank, author of “The Conquest of Cool.” “Everyone is looking for an authentic way to live, to be. People imagine that this is a stylistic rebellion. What they don’t realize is that this is what fuels our economy now. Marketing now creates the need for hip. With grunge, the corporations essentially bought an entire street culture. It was horrifying to watch.”

“In the ‘60s and ‘70s, there were legitimate movements,” he adds. “Now there’s nothing. Or at least nothing in the conventional definition of hip. I personally think the labor movement is hip, but then I am strange.”

“I have a real fondness for the hippies,” says Ann Powers, pop music critic for the New York Times and author of the newly published “Weird Like Us: My Bohemian America” (Simon & Schuster). “I see people in the indie rock scene who have been there for years, and their music has become more about consistency. But the media is not interested in that--it constantly needs a new market. The feeling is that youth are the best shoppers and should be catered to.

“Which is ironic when you consider that real teenagers and college-age kids are not treated very well by anyone else--by teachers or cops or parents.”

Commodifying the Culture of Rebellion

Hip is the armor adopted by those who feel they are being treated unfairly by society--beaten down, as the Beats explained. And it is difficult for individuals who have identified themselves as outsiders or rebels in their formative years to let go, even when all evidence proves that this is no longer the case.

“Most people raised in the post-’60s culture have a clear demarcation,” says Ulin, who is working on an anthology of Southern California literature for City Lights Press, once ground-zero for the hip literati. “ ‘Hip’ and ‘square’ means us and our parents. The whole culture is so adolescent--we are still seeking teenage credibility. We iconified radicalism as teenagers, and we can’t seem to put it aside.”

Not even when the people embracing hip are so far from being disenfranchised they are the franchise. Rich kids have appropriated the trappings of the subculture since its birth, but now money is as essential to today’s hip as jazz was to hep.

“Hip has always been connected with capitalism,” Powers says. “The racial crossovers were made possible only by money. But now the rich are the hippest people in America, which is so [messed] up because the fact that people are making millions of dollars is not new or cutting edge, it’s just how the system works.”

The new hip looks suspiciously like the old hip or, rather, the decades of the old hip put through a blender. The American-Spirit-smoky coffeehouses are often Starbucks, filled with self-consciously disheveled 20-somethings dressed in low-slung pants and lots of black. There are a few refinements--the traditionally requisite exposed midriffs are accentuated by the newly requisite navel rings, and there are, in general, a lot more tattoos . . . especially on girls.

But despite its appearance of liberalism, Power adds, “the new hip is really very conservative. It’s not interested in anyone who isn’t rich. And most people are not rich. But where you used to be able to take solace in your hipness, now, if you can’t translate that into a dot-com, you’re a loser.”

Even hip-hop and rap culture, she says, have become more concerned with their pocketbooks than their message.

What Comes After Hipness?

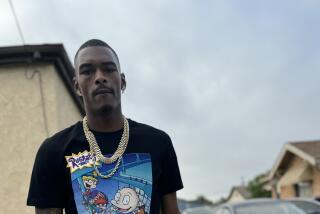

There certainly remain those who would fit a purist’s definition of hip. The music scene may be the best place to find them; rock stars--Beck, for example, or Magnet Fields’ Stephin Merritt--continue to tread the fine line between hip and commercial success with crazy grace. And there are still street hipsters, but they’re not the ones buying jeans because the model in the ad is reading Junky magazine, or paying $9 for a cosmopolitan at the latest hot club. They are what they have always been--mostly young, disaffected, and poor, often on drugs, living lives that most Americans over 30 would not find, well, comfortable.

Certainly not lives that work as a blueprint for the aging and increasingly affluent mainstream.

If the purpose of a counterculture is to raise a society’s consciousness, hipsters have done their job. The rigid definitions once applied to art and politics, to gender roles and sexuality, to career and spirituality have been sundered, or at least significantly bent. We continue to grapple with our feelings toward drugs--condemning the havoc they wreak and then using them as a symbol of enlightenment in “American Beauty.” But if hip has been a successful phase in our social evolution, why can’t we seem to move past it to the next step?

“The lack of self-esteem among people in my generation is astounding,” says Powers, who is in her mid-30s. “They believe being hip and young is all they had, and if they move beyond that, they give up all credibility. My mission [with my book] is to say you can move into the mainstream and still be who you are.”

“There is a planned obsolescence about hip that just can’t last,” Thomas says. “Trendiness does not appeal to people who don’t have money, who are occupied with other concerns. But hip will always sell better than wisdom.”

“The question comes down to how do you live an engaged, autonomous life with integrity?” Ulin says. “Not buying into corporate culture, but not living in constant reaction. We have to look at why we are so reliant on external validation, why we can’t just get beneath the buzzwords and live.”

Which is, actually, what most Americans are doing. Sure, we may flip through Details while sipping an espresso, and make occasional forays into Urban Outfitters or Abercrombie & Fitch, but until someone figures out how to make day-care hip, or Costco, community service or carpooling, most of us are going to remain outside the hip mainstream. With the well-reported concerns about schools and job security, a return to organized religion and teaching kids good values, most Americans may resemble the parents of the 1950s more than we care to admit.

But we can take solace that in doing so, we are rebelling against the hip mainstream. And if rebellion is truly hip, then 40 years later, it may truly be hip to be square.

Mary McNamara can be reached at [email protected].

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.