Netscape Co-Founder Reflects on New Wave of Internet Companies

SAN FRANCISCO — Marc Andreessen, one of the giants of the Internet, led the university team that designed the first mainstream Web browser, a tool that made it possible for average people to navigate the Web.

Andreessen took the Mosaic concept to entrepreneur Jim Clark, and in 1994, with funding from venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, the pair founded Netscape Communications, the first pure Internet company to sell stock to the public.

Their product was so formidable that software giant Microsoft later developed a rival free browser and included it with its Windows operating system, gaining and finally overtaking Netscape in market share. The tactics became one of the foundations of the Justice Department’s antitrust suit against Microsoft.

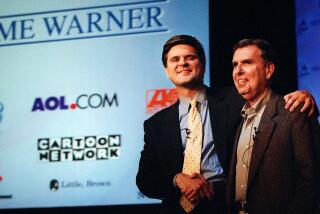

America Online bought Netscape last year for $9.6 billion, and Andreessen embarked on another radical career shift, becoming chief technological officer of an 800-pound gorilla, one with unmatched market reach and ease of use.

At 28, Andreessen has been among the highest echelons of technological invention, one of the pioneers in what has become an unprecedented stock market gold rush for all things Internet, and an executive corporate behemoth.

Last fall, Andreessen switched tacks again, co-founding a Silicon Valley company called Loudcloud.

Loudcloud, which has fewer than 100 employees, will compete with IBM and others in helping Internet start-ups with the hardware and software they need to get up and running.

Andreessen, who is chairman and a major investor in the company, recently announced new venture funding for Sunnyvale, Calif.-based Loudcloud and explained more of its plan. He also weighed in on a number of other issues in the evolution of the Internet and his own journey. The following are excerpts from an interview in The Times’ San Francisco bureau last week.

Question: What is Loudcloud doing?

Answer: We are running what I call a software power grid for high-growth Internet companies. Any of the “dot-coms” that you see out there, that stuff is really complex and is getting much more complex. Every individual dot-com is forced to hire huge teams of experts in all these different areas of technology and put all this stuff together by hand. So we are taking all that complexity and we are building a service that is like a power grid. And you can basically get as much of the software, Web server capacity, database capacity, storage capacity and so on as you need. You pay by the month, and you pay by how much you need--just like you pay the power company. That means if you are a dot-com, you can market a lot faster, you can grow a lot faster because we can help you scale up. You can focus on your business.

*

Q: How many people does a dot-com need? A chief executive and a chief operating officer and what else?

A: In the extreme case, you can do a new dot-com by writing three checks. Write one check to AOL or Yahoo or somebody for your traffic for your users. You write a second check to Scient or Viant or Razorfish to actually build your site, do the creative and do the front end, the user interface and all that. You can write the third check to Loudcloud to actually run the whole thing. In practice, it depends on what your business is. If you are going to be a content site, then you need people to write the content. If you are a sporting goods company, then you need people to do sporting goods buying.

*

Q: What do you personally get out of this?

A: We get paid. We get paid a lot.

*

Q: The upside would be some sort of venture capital angle, and you aren’t doing that, right?

A: It depends. What happens is we just become a very big utility, sort of a big power grid for all these companies and then they pay us. If they grow, if our customers grow, if they grow every month, they pay us more every month and the whole thing just gets better and better and bigger and bigger.

*

Q: How did you come up with the idea?

A: We decided to do a start-up, and we listed 15 different ideas for dot-coms. The problem with every single one is that you would have to get to market incredibly fast because there would immediately be a dozen venture-backed competitors. Then there’s all this sort of really complex stuff, all the servers and systems and databases. So we said, “Maybe we should do all that stuff first, and then we should drop in whatever new idea we come up with down the road.” Then we said, “Wait, the actual idea for the company is to do that for everybody.” So we kind of stumbled on it.

*

Q: What was your reaction to the AOL-Time Warner deal?

A: First I was surprised, and the sadness [set in] because the stock price dropped. But the more I look at it, part of it is sort of AOL’s worldview. AOL and Time-Warner actually have a lot more in common than AOL and Netscape ever did. If you look at AOL’s goal as putting together a complete consumer Internet experience, with all of the different kinds of content and services that the consumer is going to need, wrap it up in a big bow and be able to put it under the Christmas tree for hundreds of millions of consumers, it is a great thing. It also happens to solve their cable problem.

*

Q: What do you think about where Microsoft is heading strategically?

A: I think Silicon Valley by and large is deluded about Microsoft. Microsoft is stronger now than it ever has been. They are stronger on the server than they have ever been, and their Internet position is stronger than it has ever been. They will have 100% browser share pretty soon now, if all the current trends continue. They have essentially taken over the e-mail market with Outlook.

What could they do with it? They could control Internet content and formats or bias the browsing experience with their own content and services. All kinds of stuff. I think that they are just getting started on that.

I think AOL will continue to do well because I actually think Microsoft and AOL are in different businesses in a lot of ways. Like Microsoft and Sun [Microsystems]. There is a lot of noise back and forth and a lot of bad-mouthing, but they are still selling to different customers.

*

Q: What else do you think is interesting right now?

A: Certainly the whole shift in the software industry business model. There is a whole ecosystem of service providers and software services and e-services of all kinds of different shapes and flavors and colors emerging. I think we will be involved in a lot of that and supporting this sort of environment.

Two, consumer electronics. I am an investor and used to be on the board of Replay [Networks], which is coming public here pretty soon. What is happening in that whole space of Replay and TiVo and Palm [Computing] and Handspring is new kinds of connections and consumer electronics models, products, services and delivered over the Net. What is happening in wireless is tremendously interesting, especially in Europe and Japan. There are a whole bunch of new e-commerce models, a whole bunch of new business models and a whole bunch of ways to do new marketplaces that weren’t really possible in the real world.

*

Q: Do you have any investments in, or are you on the board of, any Linux companies?

A: Not currently.

*

Q: Do you have an interest in it?

A: Yes, an interest, although you’ve got to just think through how exactly will money get made. I never want to disagree with the stock market, but I am not sure I’d want to be involved with a business that is selling for $50 a copy of something that you can also download off their Web site for free. I have actually been in a business like that before. After a while, it gets a little nerve-racking.