Angel in the Outfield

The teacher is gone now, but the lessons endure. On cool Arizona mornings during spring training, and on warm California afternoons each summer, Darin Erstad and Tim Salmon practice outfield drills handed down by Joe DiMaggio.

Erstad runs toward line drive after line drive, mastering the quickest route to the ball. Salmon gauges high fly after high fly, keeping the descending ball in front of him so he can charge into a powerful throw.

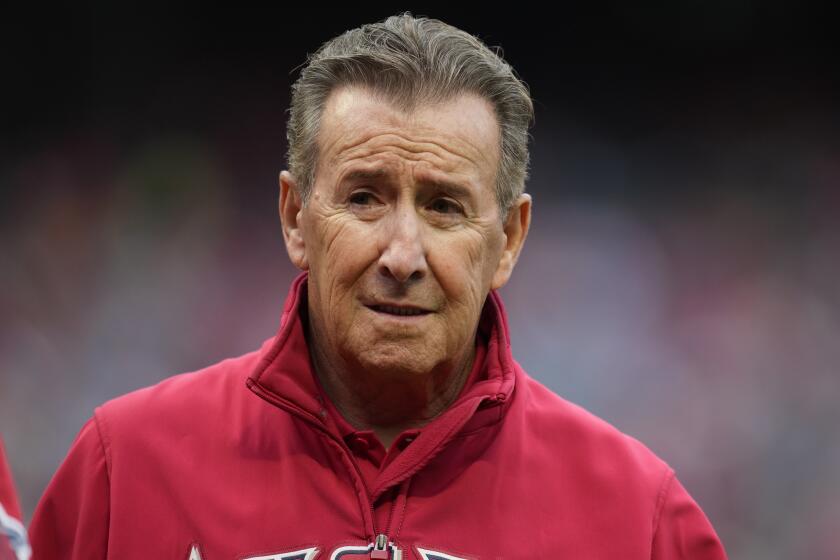

Erstad and Salmon are pupils of Sam Suplizio, the Angel outfield instructor. As a prize New York Yankee prospect four decades ago, Suplizio was a pupil of DiMaggio, who died in March at 84.

“I had the best instructor you could possibly have,” Suplizio said. “The guy was fantastically good. He could impart what he did. A lot of guys can’t do that.”

DiMaggio concluded his Hall of Fame career in 1951. Mickey Mantle arrived at Yankee Stadium that year, playing right field, before replacing DiMaggio in center field in 1952.

Injuries ravaged Mantle’s knees, and the Yankees eventually considered searching for a center fielder that would enable them to return Mantle to right field. In 1955, the same year Roger Maris hit .292 with 19 home runs at Reading of the Eastern League, Suplizio hit .298 with 24 homers at Binghamton in the same league.

In the spring of 1956, Yankee manager Casey Stengel pulled Suplizio aside. With another strong season in the minor leagues, Stengel told him, Suplizio could play center field for the Yankees in 1957. However, in a minor league game in 1956, Suplizio fractured his throwing arm in seven places, and he could not recover enough arm strength to make the majors.

By that time, though, Suplizio had long since considered a coaching career. He attended spring training with the Yankees from 1955-57, with DiMaggio coaching the outfielders each year.

“I went home and I wrote down everything I learned that day,” Suplizio said. “I still have the papers.”

Suplizio has met many a famous person inside and outside baseball. In addition to his part-time duties with the Angels, Suplizio ran a highly successful insurance business in his home state of Colorado. For the past 37 years, he has overseen the National Junior College World Series in Grand Junction, Colo., at a field since named in his honor.

He also co-chaired the task force that helped deliver a major league baseball team to Denver. In the wake of that excitement, Republican party officials urged him to run for governor of Colorado; he declined.

He has talked politics with presidents, yet he treasures most the lengthy conversations with DiMaggio about the most efficient way to catch a fly ball or run to one.

“When the subject was baseball, he’d give you all you wanted and then some,” Suplizio said.

When the subject was not baseball, DiMaggio hardly said a word. He was an intensely private man to start with, even more so in the wake of his 1954 divorce from Marilyn Monroe.

“He was a very introverted man who had obviously been hurt personally, and quite badly, by the divorce,” Suplizio said.

“He really was disturbed by the hounding of the public. I would watch him after workouts, and he’d practically have to hide to avoid people.”

How would DiMaggio have handled the contemporary atmosphere, where television cameras follow a player’s every step and where no player’s life is completely private?

“I’m sure he’d make it today, and he’d be a star,” Suplizio said. “His difficulty would be in handling the off-the-field attention, but we have a lot of people today who don’t handle it well. He’d fit in just fine.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.