Northern Ireland Vote Embraces Peace Accord

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — In an emotional bid to turn the tide of 30 years of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, Protestant and Roman Catholic voters streamed to the polls in record numbers Friday and voted overwhelmingly to endorse a power-sharing peace agreement, an exit poll showed.

Seventy-three percent of voters in Northern Ireland approved the watershed Good Friday agreement, while 96% of voters in the Irish Republic voted yes, according to the exit poll from Irish state television.

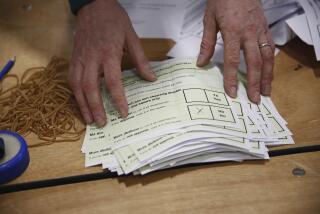

The balloting took place without any reports of violence. Official results are due today after the paper ballots are hand-counted.

A simple majority is required for the agreement to be adopted, but even supporters said that a more emphatic yes was necessary in Northern Ireland to make the deal work in such a polarized society.

Public opinion surveys conducted before the vote showed Northern Ireland’s Protestant majority moving toward the “no” camp. Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble, who headed the Protestant team negotiating the accord, had said he was shooting for a 70% affirmative vote to send a clear message that people on both sides of the Protestant-Catholic divide want peaceful change.

“This is a tremendous result,” Ulster Unionist spokesman Steven King said after hearing the exit poll early today while politicians slept. “The leadership will be jubilant.”

If the exit poll is correct, a majority of both Catholic nationalists and pro-British Protestants supported the agreement, although there was a gulf between the two groups, with 99% of Catholics voting for the deal compared with 51% of Protestants. The poll had a margin of error of 2.5 percentage points.

Nonetheless, the result represented a victory for Trimble, who bucked strong opposition from within his own party, and for British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who made three trips to Northern Ireland in the final days of the campaign to shore up Protestant support.

Most of all, it was a victory for the people of Northern Ireland who decided to abandon their generations-old tribal divisions to build a new cross-cultural society for the next millennium. It was a decision that filled many with fear and, they say, risks failure. But they made it.

Polling officials said that Friday’s turnout was higher than usual for elections in the province and said that as many as 80% of registered voters had cast ballots in the referendum.

Feeling the weight of history on their shoulders, some voters were still debating the pros and cons of the accord on the way to the polls. Others held family meetings Thursday night or gathered in pubs with friends to dissect the deal forged by U.S. mediator George J. Mitchell, Britain, Ireland and eight Northern Ireland political parties, including Sinn Fein, the Irish Republican Army’s political wing.

Still other voters said they knew early on that they would support an accord that offers hope for ending the strife that has taken more than 3,200 lives and for paving the way toward a more stable future in the beleaguered province.

“I don’t care about a united Ireland. I want a united Ulster. I want the two religions to live together,” said Catholic retiree William McCann, 72, in the town of Lurgan.

Eoin Smyth, 25, who works at a McDonald’s in the Protestant town of Portadown, observed: “I’m voting yes. This is the way forward.”

In its parallel referendum, the Irish Republic endorsed a plan under which its 1937 constitutional claim to Northern Ireland will be revised to allow residents of the province to decide their own fate.

It was the first time since 1918 that residents of the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland voted on the same day.

The 26 counties of the Irish Republic were given independence in 1921 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty that left the six counties of Northern Ireland a part of Britain. The members of Northern Ireland’s Protestant majority think of themselves as British and want to remain under the crown, while most minority Catholics want to reunite with Ireland.

The sides, with the IRA and Protestant paramilitary forces at the fore, have been locked in a 30-year struggle that has become known as “the Troubles.”

The agreement calls for Northern Ireland to remain a part of Britain unless a majority of the residents decides otherwise. At the same time, it turns local government over to the people of Northern Ireland and gives Protestants and Catholics a shared say. An election is to be held June 25 for a 108-member Belfast legislature, from which a 12-member executive will be drawn. Important decisions will require both Protestant and Catholic support--a built-in guarantee that one group does not dominate the other.

The strong popular support for the accord will make it difficult for unionist opponents to follow through on their threats to try to block implementation of the agreement from inside the assembly.

The deal will also create institutional links to Ireland and Britain. The new assembly and the Dublin-based Irish Parliament will form a North-South Council, the first official body to coordinate policies across all of Ireland since the end of British rule in the south. A Council of the Isles will join the governments in Belfast and Dublin, the Irish capital, with London and new legislative assemblies being set up in Scotland and Wales.

While Catholics overwhelmingly supported the agreement, many Protestants rejected it on the grounds that it would give Sinn Fein a role in the new Belfast government and allow early parole for prisoners belonging to paramilitary groups observing a cease-fire. The IRA has maintained a truce since July.

These issues divided even the leadership of Trimble’s Ulster Unionist Party. Six of its 10 members of the British Parliament opposed the accord.

Many Protestants said they moved into the “no” camp after IRA prisoners convicted of murder were furloughed from prison to attend a Sinn Fein congress in Dublin to approve the peace agreement.

“It’s peace at any price,” said Jim Patterson, 35, a truck driver.

Harry Hamill, 32, a Protestant art professor walking to the polls in Portadown with his two young sons, noted: “You want to vote yes, but there’s some things that stop you, like the prisoners getting out. It’s really hard, honestly. This has divided families.”

Under the accord, political parties are to renounce violence and work for the decommissioning of weapons by their affiliated armed groups. Unionists want the IRA to hand over its guns before Sinn Fein takes any seats in government.

A poll published in Thursday’s Dublin-based Irish Times found that 60% of Northern Ireland voters backed the accord, 25% opposed it and 15% were undecided. Within the Protestant majority, opinion was evenly split, with about a fifth of Protestants undecided.

Blair worked the streets and television shows of Northern Ireland to win over undecided Protestants.

“I understand the concerns that people have about this agreement, and I’ve tried to meet them, but I honestly believe it represents the best chance the future has got in Northern Ireland,” the British prime minister said.

President Clinton also appeared on television with Blair in a broadcast from England, asking the people of Northern Ireland “to vote their hopes and not their fears.”

But it may have been the Belfast appearance of Irish singer Bono of the rock group U2 that helped stem the flow of Protestant votes into the “no” camp. Bono locked hands on stage Tuesday night with Trimble and moderate Irish nationalist John Hume of the Social Democratic and Labor Party and welcomed “two men who have taken a leap of faith out of the past and into the future.”

That image sent a message to voters that this referendum was about political unity more than political prisoners.

To supporters of the agreement, the vote was also about political maturity.

“I feel it’s time the nation grew up and made adult decisions instead of knee-jerk reactions,” said Pamela Anderson, a Protestant mother of two teenagers who works in the family’s pharmacy in Portadown.

Foes said a no vote meant they don’t want the IRA to govern the province. They also said passage of the accord would lead to a united Ireland.

“The Union [with Britain] is safe,” said one opposition poster. “So was the Titanic.”

Fear, distrust and disillusionment fed the opposition. Daryl Gault, an unemployed father of six in Portadown, said his extended family discussed the agreement in his mother’s living room for 1 1/2 hours Thursday night and that all 11 voters decided to cast “no” ballots.

“We all believe it’s not going to work. There have been so many promises and so many letdowns,” Gault said.

But in Belfast, car dealer Ken Oliver called the accord “a compromise” and said he voted for it even though the IRA blew up his business in 1976 after he had poured “every penny I had” into it.

“This is for my grandchildren,” Oliver said. “I feel I owe it to them. They don’t have to live through another 30 years of this.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.