Beloved

NEW YORK — She is one of the world’s most celebrated authors, the Rev. Calvin O. Butts III told almost 2,000 congregants at the Abyssinian Baptist Church here Sunday. “And if there’s anybody on Mars who knows what we’re doing down here, she’s celebrated there, also.”

Here in Harlem, where almost 30 years ago the Princeton professor and author of a string of top-selling novels gave her first public reading, her credentials were met with acclaim. But what mattered most in the grand sanctuary of the church made legendary by the late Rev. Adam Clayton Powell was that the Nobel Prize-winning author was known more simply this Sabbath as Sister Toni Morrison.

“Sister Beloved,” said Pastor Butts, using the fond honorific of his denomination. “That’s probably the most important thing.”

Newcomers at Abyssinian stand to be welcomed, and as Morrison rose, the crowd thundered its greeting. Soon, the whole church was on its feet. Butts beamed down from the marble proscenium. Morrison smiled and let her eyes circle the sanctuary. It was a sublime moment. “Reverential,” Morrison said later.

Without doubt, the feeling was mutual. Following the service, Morrison read from her rich new novel, “Paradise” (Alfred A. Knopf). It seemed fitting, she agreed, to come back to Harlem to launch the final volume of the trilogy that began with “Beloved” in 1987, followed five years later by “Jazz.”

Morrison, a Depression-era daughter of a ship welder and a homemaker from Lorain, Ohio, was an editor at Random House when her first book, “The Bluest Eye,” came out in 1970. She had two young sons and a marriage that was foundering. Life was chaotic enough--and a career as a writer, at that point, sufficiently unreal--that the debut novel of Chloe Anthony Wofford came out with a childhood sobriquet for a first name and a soon-to-be-jettisoned-husband’s patronymic for a surname. By the time she saw the first dust jacket, it was too late to think of becoming anyone other than Toni Morrison.

When the owner of a Harlem bookstore called Liberty House and asked her to come up and read from “The Bluest Eye,” Morrison jumped on the subway and got off at 125th Street. The only piece of furniture was an old barber’s chair in the center of the store. She sat in the chair and captivated her audience.

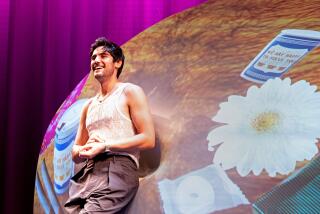

Now, at 66, Morrison was once again enthralling her listeners, albeit in a setting of considerably more grandeur. The marble stage was so slick it was scary, Morrison said later. But standing there in a long black dress slit boldly up one side, she looked regal, not remotely tentative. She wore gold hoop earrings, gold-heeled pumps and a golden pendant shaped like the continent of Africa. Her hair has turned smoky; wrapped in dreadlocks that twisted halfway down her back, it looked like a skein of soft gray wool.

“Paradise” is a strong novel that plays with paganism and with the complicated religious fervor of a fictional, all-black hamlet in Oklahoma in the 1970s. For her reading, she carefully selected a pair of churchy passages. “I thought it would resonate in this place,” she explained afterward. “And there were not a lot of suitable sections.” She threw back her head and laughed. “Paradise” is nothing if not an ironic title for a book she thought about calling “War.”

With an obvious pride of ownership, she read her prose in clear, passionate tones. Her listeners on Sunday loved it. But what they really relished was the long question-and-answer period that followed. Almost to a one, they began with near-devotional homage.

“Ms. Morrison,” said her first questioner, “let me thank you first of all for your deep and abiding love of black people.”

“Ms. Morrison,” said another, “I have to start by thanking you for the body of your works.”

How does she develop names for her characters? “Generally speaking, they have to introduce themselves to me, with a name,” she replied--although, she added, “I have worked with characters where I later concluded that what I thought was their name was not their name. I found it difficult to get them to say or do anything interesting.”

When did you know, another questioner wondered, that you would set a pen to paper? “I didn’t want to be a writer as a young person,” she disclosed. “I was quite happy to be a reader. And I do not remember my life, literally, before I could read. I didn’t come to life as a writer until I was in my 30s.” She paused to survey an audience in which many members were considerably older than that. “So,” she declared, “there is always hope.”

Love and its enduring complexity is a frequent theme for Morrison. God has a habit of showing up, too, although not always in the most benevolent of capacities. An audience member wrapped up this duality by inquiring, “If God is love, why does it seem God has given us so much trouble?” To which Morrison responded, “That’s a private question.”

The solemnity of this exchange was shattered when someone else--a published poet, he wanted it to be known--demanded, “Very simply, do you think you’re great?”

Again Morrison tossed back her silvery mane. Along with her audience, she laughed hard.

“Well, I thought that long ago,” she said.

Morrison also revealed that she is “certainly eclectic” in her musical preferences, but that she especially enjoys blues and jazz--Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor, to be specific.

She said she has a special time to write, “which is very early, too early to tell you, because it is embarrassing.” But she has no special place to write. In fact, “I didn’t even have a desk until ‘Song of Solomon.’ ” She works “for years and years” to capture the cadence of conversation, she confessed. She listens hard, not just to what people say, but to how they say it. “It requires me to do a lot of revision,” she said, “so that the affect is complicated, although the language is not.”

To another audience member who inquired about “Paradise” as “a feminist, separatist Utopia,” Morrison answered that the book probably should not be categorized “in the vein of traditional, historical, committed feminist writing.” But yes, she conceded, “I was questioning and interrogating some of the assumptions about feminism.”

And when asked about her favorite young, black writers, Morrison was diplomatic. Any list of contemporary African American literature would leave out somebody, she said, “and I will go home and think oh-oh, I left out so-and-so.” What’s more important, she said, “is that the readership is so much stronger, and the scholarship is so much more intelligent. I feel very encouraged.”

Listening to Morrison was much like reading her books, said Joshie Armistead, one of the original Ikettes from the old Ike and Tina Turner Show and now a full-time writing student at the New School. “It’s like in song. Some of the language she uses makes the hair on the back of your neck stand up,” said Armistead. “It’s a spiritual conversation that moves you. But it has to be genuine. And yeah, this is genuine.”

Seven months pregnant with her first child, social worker Sabrina Ndiaye said she had “been in love with” Morrison and her books since she was a kid. “She’s like a puzzle,” Ndiaye said. “You can’t just read her--or listen to her--and understand everything right away. You have to figure out that puzzle.”

In the minister’s chamber afterward, Morrison sipped tea and reveled in the remarkable reception. Some of the people who asked her to sign books brought six and seven copies of “Paradise,” Morrison marveled. “That’s not iconography,” she said, brushing off a suggestion that she has become a kind of African American literary goddess. “You can buy one book if you want someone to be an icon.”

Besides, said Morrison, the 1993 Nobel Prize for literature did not turn her into someone she never was before. “I’ve been a Nobel laureate for what, four years?” she asked. “I’ve been a novelist for almost 30.” Readers such as those who packed the church on Sunday know her, and they trust her, Morrison maintained.

“They know that I can be dead wrong. But I will never lie, not in the books. I am always an unblinking eye,” she said. “And I am always trying to say what it is, what the truth really is. I never avoid the risk.”

But risk can breed controversy. Just last week, a Maryland school district removed “Song of Solomon,” Morrison’s third novel (1977), from high school English classes on grounds that it was “way too graphic” in its depiction of, among other activities, breast-feeding.

Already, “Paradise” has some reviewers steamed because of its portrayal of a group of loose cannon women living together in a onetime convent. “They hang around the garden and mess up men’s lives,” she said. Morrison expects that others will object to some of her novel’s pack-mentality male characters. With fierce zeal, they operate as a kind of posse, letting nothing stop them from a horrible, grim mission.

“They never say oops,” said Morrison. “They just continue with their assault, or their rape, or their war, or whatever they were doing.”

Even in the make-believe town of Ruby, Okla. (population 360), this conflict serves as a universal metaphor, “not for war in the male, World War II-sense,” Morrison said. “But for internecine, intercommunity, class, age, gender” battles.

“All these oppositions are a kind of war,” she said. “And we are besieged. Even in 1998, I find that we are besieged.”

Luckily, there is love to act as a countervailing force. Love is what links “Beloved,” “Jazz” and “Paradise,” said Morrison: “Excessive love, the love of a parent for a child in ‘Beloved.’ Romantic love in ‘Jazz.’ And this one, ‘Paradise,’ is focused on the pride that is involved in the love of God.”

Just now, lurking at the base of her brain, there is a thought that, maybe, might take seed as her eighth novel. “There’s a little bit of something back there,” she said. “I hope it’s real.”

But for now there is “Paradise,” just racking up reviews and with an enormous press run. Later this year, “Beloved” will come out as a movie from Disney. Oprah Winfrey, Danny Glover and Tandy Newton will star; Jonathan Demme is the director. And, dividing her time between a Manhattan apartment, a house on the Hudson and a place in New Jersey, Morrison is also busy teaching at Princeton, guiding young writers by showing them “the false bottom in their hat, and then helping them to pull the rabbit out of it.”

After all, as Morrison told one questioner who wondered, persistently, why she hadn’t switched to screenwriting, fiction is power. Fiction tells the story. It writes the history. It sets the record. Fiction is what she does.

“And I want to do what I do even better,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.