Hit By A Bombshell

DESERT HOT SPRINGS, Calif. — Marilyn Monroe lives here, in spirit, on an abandoned desert ranch beneath an impossibly blue sky, where flies buzz and coyotes howl, across the freeway and a world away from the luxurious resorts of the Palm Springs area.

Marilyn Monroe lives here, in the heart of an old ballplayer whose chance meeting with Hollywood royalty 3 1/2 decades ago steered him toward a life helping children.

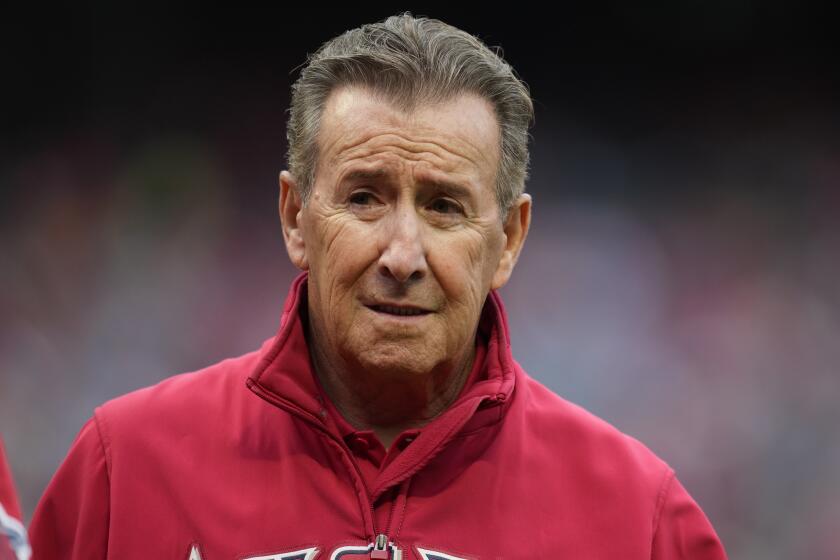

“That’s been a burden on my heart since I left baseball,” Albie Pearson said. “I have a desire to see young people with no hope given that.”

Gene Autry, America’s favorite singing cowboy, bought a baseball team in 1960 and rounded up his Hollywood friends for nights at the ballpark. As the first regular leadoff hitter for Autry’s Los Angeles Angels, Pearson met Cary Grant and Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra. Pitcher Bo Belinsky dated actresses Ann-Margret, Tina Louise and Mamie Van Doren.

The parade of handshakes and hugs mattered little to Pearson, at least until one spring evening in 1962. Pearson, asked to escort a celebrity onto the field to receive a charity donation, found himself face to face with America’s most glamorous face.

Albie Pearson met Marilyn Monroe.

“I looked at the most famous yet loneliest person I ever saw in my life,” Pearson said. “She was a beautiful shell.

“I was shocked. I expected her to come out flashing a big smile, and I got this sober look. Every Bible verse I ever heard about the love of God poured into my mind.

“But I didn’t want her to think I was a religious nut. I didn’t want to say anything.”

Actually, he did want to say something. Religion had its place, though, and the ballpark wasn’t it, not 35 years ago.

“Baseball players lived a hard-nosed life back then,” said former Angel manager Buck Rodgers, one of Pearson’s teammates. “You didn’t sit out because you were injured or because you were hung over.”

Today, star outfielder Tim Salmon helps organize weekly chapel services in the Angels’ clubhouse. Three decades ago, Pearson dared not preach in the clubhouse because, he said, “I didn’t want them to think I was weird.”

Pitcher Al Worthington proclaimed his faith, and he played for five teams from 1959 to ’64. Clubs branded him a “troublemaker,” according to Rodgers, because of his “Bible thumping.”

So Pearson remained silent as Monroe emerged from the dugout, turning on the charm as she turned to face the crowd.

She played the part of America’s sex symbol. She cooed. She posed for pictures. She shook hands with Pearson, accepted the check, and walked off the field.

Her smile, no longer required, immediately vanished. Pearson stared into searching eyes, and Monroe stared right back.

“What is it,” Monroe asked, “that you’re trying to tell me?”

Pearson opened his mouth but said nothing. He nodded, then jogged to center field for the start of the game.

Monroe never made another public appearance. Several weeks later, with the Angels in New York, the news struck like a bolt of lightning: Marilyn Monroe, three times divorced, dead of a drug overdose at 36.

In his hotel room, Pearson fell to his knees in prayer, distraught by words he never said.

“I wasn’t the cause of her death,” he said. “But I felt like I had been allowed. . . the Lord wanted me to say something to her.”

If Monroe found no peace in fame and fortune, no comfort in beauty and stardom, Pearson wondered, who could? He prayed for the courage to share his faith, the source of his peace and comfort. He didn’t know how he would do so, and he didn’t know when, but he knew that he would. For the moment, that was enough.

“I felt,” he said, “like a thousand pounds had been lifted off me.”

The Angels moved to Anaheim in 1966, as Autry and his Hollywood pals eased into retirement. Pearson retired that year too, his career cut short at 31 after a jarring slide ruptured two disks in his back.

Then, he said, he heard the answer promised him in the darkness of that New York hotel room. He heard how he would share his faith.

“Open your house to youth,” Pearson said God told him.

And so, out of the modest Riverside home of Albie and Helen Pearson, a youth ministry was born. Dozens of children, then hundreds, then thousands, descended upon his house, dropping by for friendship, counseling, job tips or Bible study.

“The neighbors thought I was pushing drugs,” Pearson said. “You can’t blame them. It was the late ‘60s.”

Something crashed against his door late one night, jolting him awake in time to hear a voice hollering, “You can have him, preacher man!” and a car screeching away. Pearson stumbled to his door, opened it and discovered a garbage can on its side.

“Inside was a young man. They had beaten him to a pulp--broken ribs, broken arm, eyes swollen shut,” Pearson said. “He didn’t pay his drug bill.

“We took him in and nurtured him. We saw his life healed in every way.

“It was worth every home run I ever hit. To see one life changed, one kid having a hope and a purpose, is worth more than any natural accomplishment I might have had.”

As the years passed into decades, Pearson left Riverside to start churches in Hesperia, Mammoth Lakes and Incline Village, Nev. He founded United Ministries International, a nonprofit corporation that sent missionaries to open churches in Spain, Italy, Russia and Mexico and orphanages in Ecuador and Guatemala.

Pearson never forgot his calling, though. At 63, he plans to open another house to the children of Southern California, swinging open the gates of an 11-acre ranch to care for abused, neglected and abandoned youth.

“There are tens of thousands of kids who have no place, no hope, no purpose,” he said. “They need to be encouraged and given purpose. If somebody doesn’t reach them, they’ll end up being part of the problem in society, not the solution.”

Pearson can’t reach them all, but he hopes to house up to 40 children here, with instructors and counselors to support them.

He will teach reading, writing and arithmetic. He will teach the Bible too, for he believes it offers the hope Monroe apparently lost all those years ago.

“I’m not trying to saddle these kids with religion,” Pearson said. “We want to care for their bodies and their minds too. But no one is complete without that spiritual foundation. You can love and teach and discipline, but when they leave here, they need to have a foundation.”

The youth home is a vision now, the ranch abandoned months ago. Where you see a slab of concrete and some pipes exposed, Pearson envisions a dining hall. Where you see a storeroom of mismatched leftover furniture, he envisions a bunkhouse that sleeps six. Where you see decaying wood barely supporting a brittle backboard, he envisions kids romping on a refurbished, repainted basketball court.

Pearson estimates he needs $400,000 to finance the acquisition, renovation and operation of the property. He prays for the money.

If he played today, he could write the check himself. But, in a nine-year career in that included honors as American League rookie of the year in 1958 and an all-star in 1963, Pearson’s salary never exceeded $33,000.

Why not apply to foundations that award grants to worthwhile community projects?

“I don’t know how,” he said.

He refuses to ask for financing from perhaps the most likely source, the very government agencies that may refer disadvantaged children to him. On this ranch, he vows, church and state will not be separated. “I’m not going to throw God out to get state or county money,” Pearson said. “I can’t do that.”

For information: Father’s Heart Ranch, 71-175 Aurora Rd., Desert Hot Springs, Calif. 92241.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.