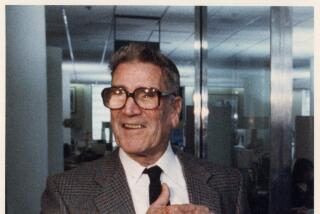

Acclaimed Poet James Merrill Dies

James Merrill, perhaps America’s greatest living poet, who penned more than 14 books of verse in addition to plays and novels, has died at the age of 68.

He died Monday in Tucson, where he was visiting, of a heart attack. Merrill had homes in Stonington, Conn., and New York City.

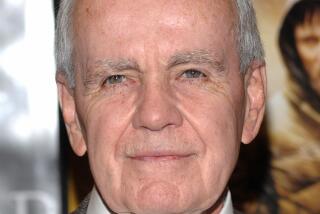

Stephen Yenser, a poet and the author of a major study of Merrill’s work, called Merrill “one of the handful of poets by whom American literature in this century will be known.”

Few would disagree. Novelist David Leavitt, reviewing an early autobiographical novel of Merrill’s for The Times (fiction was Merrill’s first ambition), wrote: “It is a testament to the breadth of James Merrill’s influence that one can, without ruffling too many feathers, declare him the greatest living American poet.”

Merrill’s work was rewarded by, among other honors, two National Book Awards, the Bollingen Prize in Poetry, the Pulitzer Prize and the Library of Congress’ Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry. In 1983 “The Changing Light at Sandover,” perhaps his most ambitious and fully achieved work, won both the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

His first book, published in 1951, was titled “First Poems.” His first play, “The Immortal Husband,” was produced off Broadway in 1955, and his first novel, “The Seraglio,” was published in 1957. His 15th volume of poetry, “A Scattering of Salts,” is scheduled for publication next month.

He was the son of Charles E. Merrill, founder of the Merrill, Lynch, Fenner & Smith brokerage firm, and Hellen Ingram Merrill. The poet was the beneficiary of a large trust fund established when he was 5. Wealth was both the condition of and an obstacle to his achievement.

Times book critic Richard Eder, reviewing “A Different Person,” the memoir that Merrill published in 1993, wrote:

“Perhaps no one born with a silver spoon in his mouth has made such specifically appropriate use of it as the poet James Merrill. As silver, it gives a fine luster to his voice; as a spoon, it comes close to gagging him. His work . . . draws its essence from two qualities: a shining beauty and a sense of impediment.”

Wealth set Merrill apart. So did homosexuality, a central subject in “A Different Person.” But nothing, in the end, distinguished him more than the beauty and brilliance of his language.

Merrill is survived by a large extended family, including his mother; his sister, Doris Magowan; his brother, Charles; his companion of more than 40 years, David Jackson; and his close friend Peter Hooten.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.