BASEBALL / ROSS NEWHAN : This Is Merely Another Sign of Instability

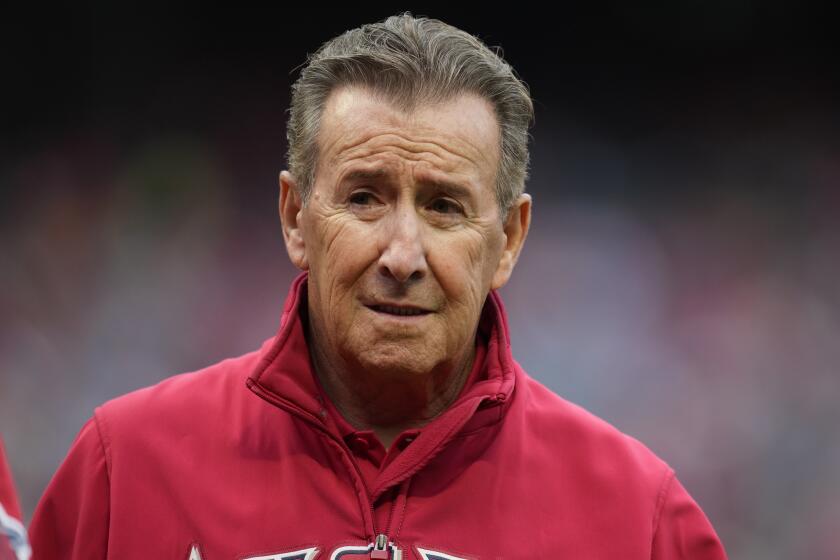

There were no miracles during Whitey Herzog’s tenure at the helm of the Angels. No World Series for the Cowboy, good friend Gene Autry.

Budget restraints, front-office infighting, trade complexities in the era of agents and arbitration, and the magnitude of the task he inherited made the wheeling and dealing Herzog pulled off with the St. Louis Cardinals in the early ‘80s impossible.

His decision to step down as general manager Tuesday and become a club consultant--he may resurface as a general manager if good friend David Glass emerges as new owner of the Kansas City Royals--seemed a legitimate measure of many factors.

Among them: the frustrations he had experienced in the Angel role; his conviction that new General Manager Bill Bavasi is ready for the assignment; his feeling, now that he is financially secure at 62, that he can do without the time and travel demands of a long-distance commute from his St. Louis home.

The Angels put their best face on it, saying Herzog had accomplished many of their most important objectives. Among those cited by club President Richard Brown:

--He helped reorganize the front office, winning a power struggle with Dan O’Brien, elevating Bavasi from scouting director, bringing in Ken Forsch to replace Bavasi and hiring longtime Seattle scout Bob Harrison as an influential adviser.

--He helped reduce a $38-million payroll to a level from which it can be judiciously rebuilt.

--He accelerated the force-feeding of top prospects from a farm system that might not be as bad as he had been led to believe, and he beefed up the Caribbean and international scouting efforts.

“We’ve been touched by a winner,” Brown said.

Perhaps, but there are nagging and familiar questions:

--What now for a franchise that has never known the meaning of continuity?

From Dick Walsh to Red Patterson to Harry Dalton to Buzzie Bavasi to Mike Port to Herzog-O’Brien, nothing seems to last.

The Angels go from one philosophy to another, one direction to another, always haunted by the imperative of winning for the Cowboy before the last roundup.

Viewed in a historical context, Herzog’s resignation is merely the latest chapter in that ongoing story.

--What now for an ownership seemingly using the same accountants as the San Diego Padres?

Restraint, of course, is admirable and building from within imperative, particularly by an organization that long ignored it, but in an era of free agency and diluted talent, no club can be fashioned in only one way.

Herzog was clearly frustrated by Gene and Jackie Autry’s parameters and often short-tempered in negotiations with players and agents.

“Anyone trying to build a club is going to be frustrated by budget restraints, but that seems to be the rule and not the exception right now,” Manager Buck Rodgers said of baseball’s economic overview.

“Whitey is the type who, when he wants to get something done, he wants to do it now and may not be a diplomat if he’s prevented from it. If the time was right, he wanted to feel he could go get that one more guy.”

Said Brown: “Any general manager would love to have the parameters of the Toronto Blue Jays, to be able to spend $51 million on a 40-man payroll, but no owner can condone losing $5 to $8 million a year and expect to stay in business. Whitey took over a $38-million payroll and a club that couldn’t win.

“He’s brought the payroll down to a workable level and built up the team in the process. Was he frustrated? I think he was frustrated by the system. As he says, you don’t trade players anymore, you trade salaries.

“I asked him the other day if he felt his hands were tied here and he said not since the reorganization (when O’Brien was forced out). He’s always been aware of the economic parameters and had a voice in establishing them. Two years ago, he told us he couldn’t live with the budget the way it was projected and we raised it $2 million.”

On the phone from Springfield, Mo., where he was being inducted into the Missouri Hall of Fame, Herzog said he was disappointed that he couldn’t get the Cowboy to the World Series.

“I thought I could do it in two or three years, but for reasons I’d rather not get into, I didn’t have the authority I felt I had when I got there,” he said.

He also emphasized that he would continue to serve the Angels as a consultant, but that a consultant is only valuable if someone calls to consult.

Bavasi might. He is Herzog’s hand-picked disciple.

Bavasi also learned at his father’s knee, Buzzie having been general manager of the Dodgers and Padres before joining the Angels. It is also noteworthy for an organization that has not specialized in stability that Bavasi moves up from within, having been with the club since 1981 and farm director since ‘84, a span in which no farm product ever accused him of deceit or mistreatment.

If Herzog laid a foundation, as the Angels claimed Tuesday, not necessarily apparent in the standings, Bavasi must build on it within parameters that at times frustrated his predecessor. Can he do it? Time will tell, but it seems as though we’ve been here before.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.