Being on Call Left Whitey Off the Hook

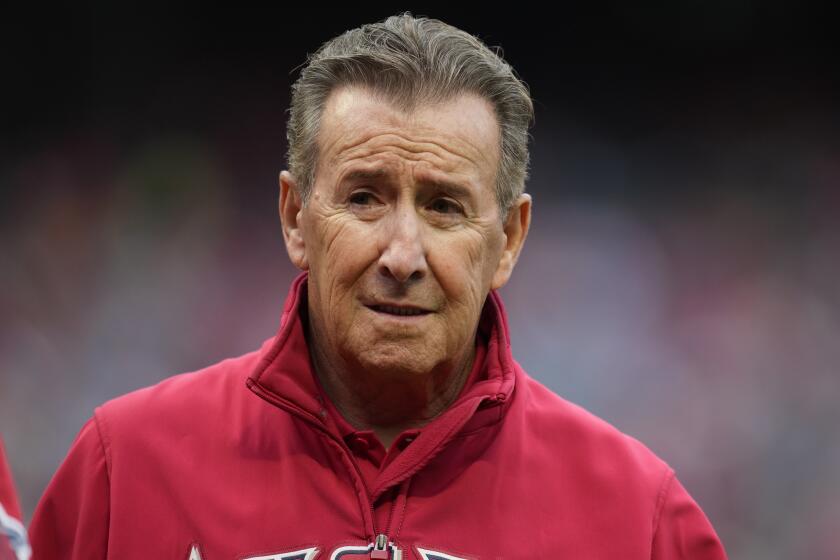

The Angels called a press conference Tuesday to announce a new role for Whitey Herzog, which, to hear Whitey tell it, will enable him to work out of his home, relax a little, spend time with the family and have “basically no responsibilities. You wait for the phone to ring and hope someone wants to pick your brains.”

Kind of like Whitey’s old role with the Angels.

Whatever the name plate said during his first 2 1/2 years on the Autry payroll, it never had it quite right.

“Senior Vice President, Player Personnel,” was what they called him when he came aboard in September, 1991.

Later, it became: “General Manager.”

And now: “Consultant.”

So the gig is up.

After 2 1/2 years, Herzog and the Angels finally decided to come clean, sweep aside the pretense and call a spade a spade--and a baseball consultant a baseball consultant.

With the Angels, Herzog has never been more than a phone call away. That’s a job description, not a location. Need to finalize a trade? Phone Whitey at the ski lodge. Closing in on a free agent? Leave a message on Whitey’s answering machine, he’s gone fishing. Think we should run a physical first on this Kelly Gruber person? Oops, line’s busy.

Some general managers end up being acclaimed as AL or NL executive of the year. With a little better luck, Herzog could have been MCI executive of the year. Herzog was baseball’s first absentee GM--he ran a ballclub based in Anaheim from his den in St. Louis--and based on the evidence before us today, the best thing he generally managed from there was his leisure time.

“The toughest job in baseball today is being the general manager,” Herzog said Tuesday, appropriately enough, on a conference call from Missouri.

“A manager, when his season is over, he can walk away from it. But a general manager’s job is never done. It’s a 24-hour-a-day job.”

Herzog and the Angels often tried to fake it, however, which is more the club’s fault than it is his. The Angels were the ones who came crawling to Herzog in ‘91, throwing money at his reputation, as if it could buy them credibility. Herzog made a few demands, one of them being his business address. He wanted to stay in St. Louis, operating the show by fax and phone.

No problem, the Angels told Herzog. Kick back, we’ll keep you posted. Anything else? Move all our home games to St. Louis? Well, we already looked into that, Whitey. Seems that the Cardinals already have the place booked.

Tuesday, Angel President Richard Brown insisted that Herzog’s long-distance relationship with the club was not a detriment. “I keep a beeper with me at all times,” Brown said. “It has an 800 number. I was never out of contact with Whitey.

“In a lot of ways, his living in St. Louis helped us. It saved us money on scouting trips to Chicago and the Midwest.”

Which explains the Angels’ recent additions of ex-St. Louis Cardinal Joe Magrane, ex-Kansas City Royal Kurt Stillwell, ex-Minnesota Twin Chili Davis and ex-Montreal Expo Spike Owen.

For those who tried to keep tabs on the Angels’ off-season maneuvering in the sports section, it also made for funnier reading than the comics page.

Last winter, Herzog traded Lee Stevens to Montreal for a pitcher named Jeff Tuss, unaware that Tuss had already left the Expos organization to play quarterback at Fresno State. Oh well, Whitey said, “he wasn’t going to be Walter Johnson anyways.”

Days before, Herzog had acquired Gruber from Toronto, only to learn later that Gruber had suffered a career-threatening shoulder injury in the previous World Series. Herzog learned this when a reporter tracked him down at a ski resort.

Five days passed between the Angels’ signing of free-agent pitcher Scott Sanderson and Herzog’s knowledge of it. Again, a reporter, phoning east, broke the news. Just last month, when the Angels had to decide whether or not to tender reliever Steve Frey a 1994 contract, the Dec. 20 deadline passed with assistant general manager Bill Bavasi failing to reach Herzog.

Reason: Malfunctioning answering machine at the Herzog residence.

On those occasions when the Angels were able to get ahold of Herzog, the news was seldom good.

Out the door, one by one, went Wally Joyner, Dave Winfield, Bryan Harvey, Jim Abbott, Mike Fetters, Mark Eichhorn, Luis Polonia.

In came Von Hayes, Hubie Brooks, Alvin Davis, Chuck Crim, Russ Springer, Gruber and Owen.

Herzog’s best trade for the Angels? Dick Schofield for Julio Valera. Valera went 8-11 in 1992, hurt his arm in camp last season, went 3-6 with a 6.62 ERA through June and underwent ligament reconstruction surgery in his right elbow on July 8. It’s uncertain if, or when, he will pitch again.

Herzog’s best free-agent signing for the Angels? Chili Davis, even though it amounted to little more than righting an old wrong. Chili, who never should have been let out the door in the first place, returned to Anaheim in 1993 and drove in 112 runs. Not quite Barry Bonds, but, then, compare the size of the contracts.

By the end, Herzog was acting primarily as executioner on the Autrys’ payroll guillotine. It couldn’t have been much fun, which probably explains why he stayed out of the office.

“Today in baseball . . . when you talk about a player, you talk about arbitration, if he has a guaranteed contract, when he’s going to be a free agent,” Herzog lamented. “We never really talk about whether he can run, hit and throw.”

The game changed on Herzog. So did the rules. Long gone are the days when he made his name as a wheeler-dealer, when he traded 14 players for 11 during the 1980 winter meetings. With the Angels, Herzog was left to pound his fist when $16 million was not enough to re-sign either Joyner or Abbott . . . or when free agents Bobby Bonilla and Danny Tartabull said maybe, only to leave him empty-handed . . . or when the local media dared to question his genius as a talent scout.

“One of the things that threw Whitey when he came here,” Brown said, “was the hostile press. He came in from Kansas City and St. Louis, where he was almost a deity. But the media here looked at him and said, ‘OK, the guy’s got a pretty good record, but what’s he gonna do here?’

“Whitey’s approach was, ‘I don’t have to show you anything. My track record speaks for itself.’ ”

Herzog had a point. With St. Louis, he was a good general manager, considerably more effective than he was in Anaheim.

But with St. Louis, he had two distinct advantages.

Money to spend.

And a St. Louis address.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.