Los Angeles Festival: “HOME, PLACE and MEMORY” A Citywide Arts Fest. : Documentary Evens the Score for Father of Mambo : Movies: Cuban-born actor Andy Garcia documents a concert honoring Israel Lopez Cachao. It’s Garcia’s directorial debut.

It was an unlikely scene, made possible only perhaps by Cuban-born actor Andy Garcia’s love of Cuban music: a crowd of 5,000 gathering last year at Miami’s James L. Knight Center to celebrate the music of Israel Lopez Cachao.

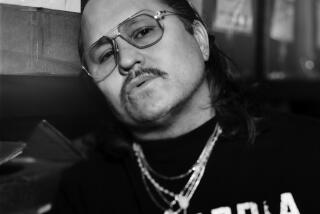

As spontaneous as the show itself, Garcia’s filmed account of the rehearsals and the concert will help bring overdue recognition to the man who is Cuban music personified. Garcia’s film, “ Cachao: Como su ritmo no hay dos “ (“Cachao: Like His Rhythm, There Is No Equal”), will open Wednesday at the Nuart Theatre in West Los Angeles as part of the L.A. Festival.

Although Damaso Perez Prado popularized the mambo dance craze on an international level in the late ‘40s, Cachao has long been known among Cuban musicians as the father of the mambo. One of the reasons Cachao isn’t better known outside of Cuban music circles is his low profile.

“I’m a very quiet man,” Cachao, 74, said recently by phone from his home in Miami. “It’s never bothered me that I’m not better known . . . but I am happy for all the help this boy Andy Garcia has given me. I love him as if he was my own son.”

Until Garcia crossed his path, Cachao mostly survived by playing birthday parties and obscure Miami restaurants. Cachao, along with his brother Orestes, composed more than 3,000 danzones (a danceable blend of Afro rhythms with Spanish- and French-derived music) in the 1920s, before giving birth to the mambo in 1938 by adding further spice to the danzon . It was a move that would change--or expand--Cuban music forever, setting the scenario for the whole salsa movement.

As significant for Latin pop music as the mambo, but even more ambitious, was Cachao’s 1957 descargas --actual jazz-style jam sessions with some of Cuba’s best folkloric musicians. With plenty of room to improvise, the descargas produced some of the best Afro-Cuban records ever, collectors’ items that were ahead of their time and became points of reference for much of the music of future years, not only in the traditional tropical field but in Latin jazz as well.

Despite his significance, Cachao has been virtually ignored by the Cuban exile community in the United States (particularly in Miami, because his African-rooted style was never appreciated by the predominantly white, well-to-do first generation of exiles).

*

“They said it presented a false image of the Cuban population,” Cachao said. The absence of an Afro-Cuban presence in Miami is eloquent.

In a Wall Street Journal article in August on Garcia’s documentary, Florida International University sociologist Lisandro Perez said that “in Cuban history, that which is African--music, religion, even ways of speaking--is associated with the lowest economic origin. Immigration here has been very heavily influenced by the Cuban elite, people who are not traditionally supporters of Cuba’s African art forms.”

But not all Cuban exiles turn their backs on their former homeland’s Afro-Cuban musical roots.

Guillermo Cespedes, the Cuban-born leader of the San Francisco-based Conjunto Cespedes band, praises both post-revolutionary Nueva Trova and traditional Afro-Cuban music, of which Cachao is the ultimate exponent.

“When I hear Cachao’s bass, I hear African drums,” said Cespedes. “Maybe he doesn’t know the difference between Congo, Cameroon and Tanzania rhythms, but his true genius and mastery cannot be disputed.”

After listening to Cachao’s music for more than 20 years, Garcia has made a directorial debut that couldn’t have had more positive effects, both for him and the mambo father.

“I’ve only spent five years in Cuba,” said Garcia, “but it was enough to instill in me the music, the color, the tremendous energy of being a Cuban. With his music and humanity, Cachao represents the best of my country. This is the least I could do for him.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.