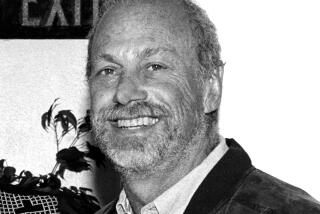

Henley Ups the Ante in Geffen Fight : Lawsuit: Singer charges that entertainment impresario conspired with record corporations to blackball him.

Don Henley is turning up the heat in his bitter legal dispute with Geffen Records, charging that entertainment impresario David Geffen conspired with other powerful record corporations to blackball the Grammy-winning singer-songwriter.

Attorneys for the 46-year-old recording artist were expected to file papers in Los Angeles Superior Court on Tuesday requesting that an antitrust violation be added to Henley’s cross-complaint, which stemmed from a breach-of-contract suit filed against the artist by Geffen.

The new amendment alleges that executives at Warner Music Group, Sony Music and EMI Music assured Geffen they would not sign any artist who attempted to break their contract under the seven-year statute--the precise law Henley cited nine months ago spurring the vitriolic legal battle.

Under the statute--a controversial California law enacted 50 years ago to free actors from long-term studio deals--entertainers cannot be forced to work for any company for more than seven years. Some record executives believe the statute won’t hold up in court, but have been reluctant to test it because an adverse ruling could lead to a wholesale exodus of veteran artists from their record companies in search of better deals on the open market. Earlier possible showdowns over the statute have been avoided because artists settled out of court for more money and upgraded contract terms.

“If powerful corporations like these are having discussions to stop me from recording my music, what does that say about the state of affairs in the music industry?” Henley told The Times on Tuesday. “Unfortunately, record companies are no longer run by people who love music. They’re run by bean counters and attorneys and all that matters to these guys is the bottom line.”

Geffen dismissed the conspiracy allegations as a publicity ploy.

“I’m about as concerned about this as I am about a baked potato I ate last week,” Geffen said Tuesday in a phone interview from New York.

“The claim is absolute nonsense,” added Geffen attorney Bertram Fields. “There was no conspiracy whatsoever.”

Some of the most powerful figures in the music business are expected to be subpoenaed to respond to Henley’s allegations, including Warner Music head Robert Morgado, Sony’s Michael Schulhof and Tommy Mottola, as well as EMI’s Jim Fifield and Charles Koppelman. Allen Grubman, the New York attorney who represents Geffen Records and who was sued last year for conflict-of-interest by pop star Billy Joel, is also expected to be called to answer questions about the conspiracy charges.

Representatives for MCA-owned Geffen Records and the other three corporations--whose distribution arms are already under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission for their policies on used CDs--declined comment on the matter.

The flap erupted in December when Henley sent Geffen a letter saying he was terminating his contract, even though he reportedly owed the company two more studio albums and a greatest-hits collection. In January, the record company filed a $30-million breach-of-contract suit in Superior Court against the artist.

Henley’s attorney, Don Engel, said the latest twist in his client’s case follows an acknowledgment by Geffen under oath that he asked the heads of several record companies whether they would sign an artist who broke their contract under the seven-year rule. The executives allegedly told Geffen they would not sign anyone who took such an action, according to Engel.

“What we may have here is a conspiracy not only against Don Henley, but one intended to revoke the seven-year-rule itself,” Engel said.

Henley concurred.

“This law was designed specifically to protect artists,” Henley added. “But what good is it if the record companies are out there agreeing among themselves not to sign anyone who attempts to use it?”

Engel suggested that the alleged conspiracy may date back as far as 1991 and could have played a part in another case he handled--a similar attempt by R&B; star Luther Vandross to break his contract with Sony-owned Epic Records. There is evidence, Engel says, that negotiations in that case may have fallen apart after at least one major record company took a similar position to boycott Vandross’ planned move to another label.

Legal experts suggest that Henley’s attorneys will have a difficult time substantiating the antitrust allegations in court.

“Conspiracy is very hard to prove in a court of law,” said Warren Grimes, a law professor at Southwestern University who served as the chief counsel of the monopoly subcommittee in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1980 to 1988. “In the typical case all you generally have is conduct that might indicate a conspiracy, but what you need is evidence.”

Several insiders also speculated that there may be a valid reason why other companies might not want to sign Henley.

Six years ago, the Recording Assn. of America, the trade organization that represents the six major U.S. record companies, succeeded in securing an amendment to the law that grants record firms the right to sue and recover damages for any product still owed the company by the performer opting to break his contract by invoking the seven-year statute.

If Geffen sued for the two albums his company feels Henley owes them it could cost any new label that signs Henley as much as $20 million in damages, sources said.

Besides the seven-year statute, Henley’s suit claims he was terminating his contract because he believed Geffen--who sold his company in 1990 to MCA Music Entertainment, which in turn sold it six months later to Matsushita Electrical Inc.--was no longer actively involved in running the label.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.