Critics to Get Taste of Own Medicine at Harvard Forum

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — “Critics are not accountable,” says Robert Brustein. “We want an exchange between the artist and the critic where they can talk about mutual problems and mutual resentments.”

Brustein was describing this weekend’s “Critics & Criticism Conference,” a series of panel discussions co-sponsored by Brustein’s American Repertory Theatre and the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University. The conference’s purpose is to examine what Brustein perceives to be a “crisis in criticism.”

After Friday’s keynote address by Times of London critic Benedict Nightingale, representatives from publications as opposite as Variety and the Village Voice will discuss the theater and its critics. Scheduled panelists include JoAnne Akalaitis of the New York Shakespeare Festival, cartoonist-playwright Jules Feiffer, Yale Repertory Artistic Director Stanley Wojewodski Jr. and Rocco Landesman, president of Jujamcyn Theatres. They will confront many of their severest critics: New York magazine’s John Simon, Newsweek’s Jack Kroll, Time magazine’s William A. Henry III and the Los Angeles Times’ Sylvie Drake, among others.

Conspicuous by their absence will be two previously announced participating critics, the Boston Globe’s Kevin Kelly and the New York Times’ Frank Rich. Although Kelly never officially agreed to attend, Rich did--only to withdraw his name.

“There is bound to be controversy and I think overtones of controversy are keeping certain people away,” Brustein said of the conference. “Rich has backed out. Kevin Kelly has backed out. So there’s some fear and trembling about being confronted by their victims, (about) being accountable. Even the Nieman Foundation is worried that there may be too much heat and not enough light. I don’t know how you can have light without heat.”

The 65-year-old Brustein should know about heat and light since he has ignited plenty of both during his career. Brustein is a critic who publicly criticizes his fellow critics, something quite rare within that elite fraternity. For instance, during this interview he called Kelly “negative and useless” and labeled John Simon “the Morton Downey Jr. of criticism.”

Brustein is unusual in another area as well: He works both sides of the stage.

Since 1956, Brustein has written drama criticism for the New Republic magazine and other publications. But he has simultaneously directed, produced and performed for the stage. His stormy 13-year tenure as dean of the Yale School of Drama ended in controversy in 1979.

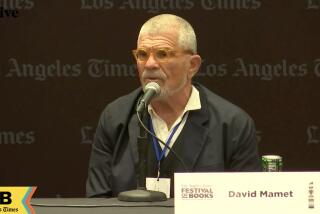

Since 1980, Brustein has been artistic director of the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, where he continues to generate controversy, as well as premiere plays such as Marsha Norman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “ ‘night, Mother” and David Mamet’s “Oleanna.”

But it’s Brustein’s criticism that attracts the most attention.

“Brustein writes very controversial criticism,” said Lincoln Millstein, assistant managing editor of features for the Boston Globe. “But he can’t take criticism. What’s gotten him into trouble is his own criticism.”

For example, in 1990 Brustein compared August Wilson, the two-time Pulitzer-winning playwright, unfavorably to Eugene O’Neill: “Whereas O’Neill wrote about the human experience in forms that were daring and exploratory, Wilson has thus far limited himself to narrow aspects of the black experience in a relatively literalistic style.”

Brustein then questioned the ethics of Wilson’s plays being developed for a commercial market at the not-for-profit Yale Repertory Theatre. He chastised Yale Repertory’s then-artistic director, Lloyd Richards, for spending more time and attention on Broadway-bound productions than on academic responsibilities.

Brustein’s critics promptly and loudly pointed out a possible conflict of interest: Richards was Brustein’s successor at Yale, and Brustein had also steered productions from Harvard to Manhattan.

But Brustein’s 1991 reaction to the Boston Globe series on multiculturalism led to more serious repercussions. The series concluded that American Repertory was negligent in minority hiring and in providing plays by minority writers. Brustein responded with a long article examining “the way a powerful newspaper can abuse its cultural influence.”

A year later, the Globe refuses to cover this weekend’s conference while Brustein has broken off communication with the area’s most influential newspaper.

“I will not talk to the Globe,” he said. “Kelly just does his kind of 10th-rate John Simon version of snarling ‘yes’ or putting his thumbs up or down in Siskel-Ebert style.”

Brustein blames ratings for the “unaccountability” of today’s critics:

“Editors seem to be delighted with the kind of controversy people like (Rich and Simon) stir up-- it sells newspapers. I’ve known Simon for a long time. In fact, I got him his first reviewing job, so blame me. But Simon changed when the media began to pick up on him. He went on television and would be absolutely abusive and insulting and the audience would lap it up. Simon became an entertainer, the Morton Downey Jr. of drama criticism.”

Just this past March, as if in a tuneup for the conference, Brustein published a widely discussed article in the New Republic titled “An Embarrassment of Riches.” In it, he dared to attack the nation’s most influential and powerful theater critic. “There is almost universal agreement,” Brustein wrote, “that a causal link exists between Rich’s dramatic opinions and the crisis in the American theatre.”

“I didn’t jump into that one with great enthusiasm,” Brustein said of his criticism of Rich. “Everyone has these stories to tell, but unfortunately they always tell these stories sotto voce. People are frightened and intimidated by Rich.”

Perhaps the coup de grace of Brustein’s criticism occurred in a recent issue of American Theatre magazine. In an article titled “The Theatre of Guilt,” Brustein stated that AIDS activist plays are a form of “moral blackmail . . . plays you’re not allowed to hate.” The magazine received so many letters attacking Brustein’s perspective that it had to print them in two successive issues.

“I was brought up believing that one should not inquire into people’s political beliefs or sexual backgrounds or their religious beliefs,” Brustein said. “I certainly don’t think it’s anybody’s business to be doing racial breakdowns of companies, although that’s happening all over now. And indeed grants are made on the basis of it. Even the NEA is insisting on that. I find it so anti-American, but I was definitely brought up in a different time. They’re trying to force us to look at people as black or as gay or as Asian or as this or that, rather than as people.”

“He began attacking his critics very shortly after he got here,” said the Globe’s Millstein. “It’s part of his strategy, I think. This is not new. He’s done it for years. I don’t know if he understands the role of a critic, even if he is a critic. A review should be the beginning of a public discourse and not the end.”

This weekend’s “Critics & Criticism Conference” may generate such public discourse, but then again, the way things seem to be headed for Brustein, it could end all dialogue. As Brustein wrote in the New Republic: “. . . (We must) end the debilitating symbiotic relationship between criticism and practice.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.