Angels’ Jackie Autry Increasingly Taking Reins From Cowboy

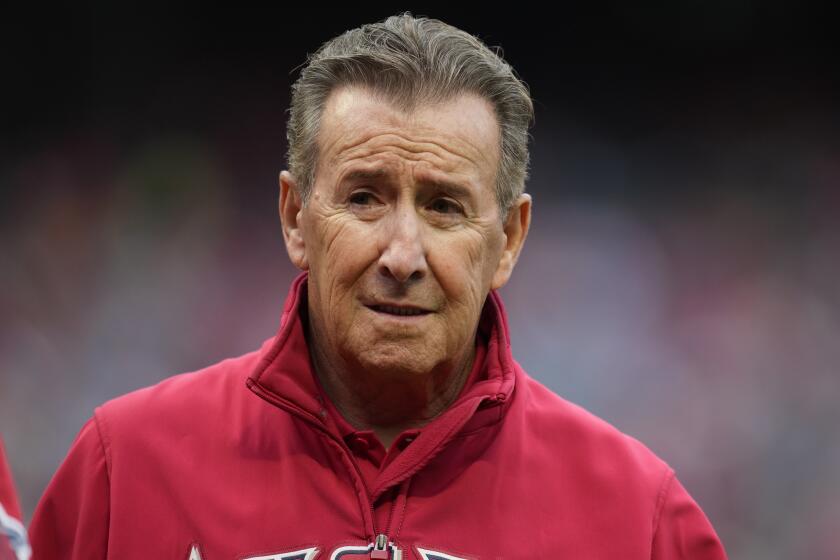

ANAHEIM — Jackie Autry watched from the owner’s box as her husband, the man they call the Cowboy, moved with tiny, shuffling steps toward home plate for a ceremony on the field at Anaheim Stadium.

Always a private person--”even when I was a banker,” she says--she is content to remain behind, out of the public eye. During a 10-year marriage to Angels owner Gene Autry, the singing cowboy who built a fortune worth more than $300 million, she has seldom joined him on the field, making a rare exception for one of his birthday celebrations some years ago.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Aug. 12, 1991 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Monday August 12, 1991 Orange County Edition Part A Page 3 Column 1 Metro Desk 1 inches; 29 words Type of Material: Correction

Jackie Autry--Because of an editing error, The Times incorrectly reported Jackie Autry’s position on the California Angels’ board of directors. She is a member of the board. Her husband, Gene, is chairman.

The birthdays have kept passing, more of them than many are blessed with. At 83, Gene Autry is defined as much by his cane as by his cowboy hat. But he still keeps score every game, and talks with club President Richard M. Brown twice daily, almost exclusively about baseball matters, Brown says.

It is Gene Autry’s advancing age and the club’s desire to win a World Series in his lifetime that has inspired a long list of expensive free-agent signings and other attempted quick fixes by the team. He remains the public’s image of Angels ownership.

But it is Jackie Autry, 49, a former bank vice president who says she was “astounded” at the club’s historic lack of profitability, who increasingly directs the operations of the club, declaring that it must stop losing money and that the free spending that has marked the fervent attempts to “Win One for the Cowboy,” must end.

This season, the team has sunk into last place in the American League West despite spending between $32 million and $34 million on player salaries. According to Brown, losses will be somewhere between $2 million and $4 million this year.

“Gene’s too old to go back to work,” Jackie Autry said, a teasing smile playing across her face, “and I have no desire to.”

She is resolute that the team must strengthen its scouting and farm systems, resist high-priced free agents and build for the future from within. Despite three divisional championships, the Angels have never reached the World Series in their 30-year history.

“Sometimes you feel that one player might do it, and that’s the temptation that you have,” Jackie Autry said. “With Gene’s age, there are times I get a sense of panic from our people in baseball operations that if we don’t do it this year, he might not be around next year. I don’t think that has been beneficial to this organization.”

Like Jackie Autry, Manager Doug Rader has also pushed to strengthen scouting and minor league development, and he in particular wants to expand the club’s Latin American scouting network. Rader agreed to a two-year contract near the end of last season only after getting assurances that the club would embark on a movement to build from within. Ironically, Jackie Autry acknowledged last week that the team’s continuing struggle and tumble to last place--the Angels led the division for one day in July--now threaten Rader’s job.

Though Jackie Autry is her husband’s staunch defender, and though she more than anyone wants to give him the World Series he has waited so long for, she is convinced that the club’s methods have been counterproductive.

“Gene has always believed in the marquee value of the name, and so we found ourselves continuing to mortgage our future by trading away these young people,” she said. “And they’ve gone on to bigger and better things.”

“We stopped doing that in 1984,” she said, referring to the Angels’ attempt at a youth movement in the mid-1980s. “That’s why we’ve had Dick Schofield--we had Jack Howell of course, who didn’t work out for us but he looked very good at the time--and Wally Joyner, Chuck Finley, Bryan Harvey, Kirk McCaskill. . . .”

But in 1989, the Angels signed pitcher Mark Langston to a five-year, $16-million free agent contract, and signed third baseman Gary Gaetti to a four-year, $11.4-million contract in January.

“I believe we have reverted in recent years to bad habits again in terms of free agents,” she said, noting that Gaetti, a second-look free agent, did not cost the club a compensatory draft pick. It is the lost draft choices, probably more than the free agent salaries, that can undermine a team’s future.

“When we signed Mark Langston, our first draft pick was 64th,” she said. “You can’t do that. That’s not a way to build a farm system.”

When the couple were first married, Gene Autry, whose first wife died in 1980, sometimes referred to his younger second wife as the “owner in training.” She now carries the title of executive vice president and is chairman of the board of directors.

She has also been named to the board of directors for Major League Baseball and is the first woman to sit on its executive committee.

Jackie Autry allows that while she grew up “a tomboy” in New Jersey who used to love to “hunt and fish, skate all winter and swim all summer,” she did not have a professional knowledge of baseball 10 years ago. She undertook to learn it.

“Gene Mauch taught me one thing,” she said. “Keep your eyes open, keep your ears open, keep your mouth shut and listen. People don’t listen, ever.”

Jackie Autry has listened, for the better part of 10 years. Mauch, the former Angel manager, has tutored her on the subtleties of the game to the level that she is confident in second-guessing Rader on the field. She can speak the language of scouts, and knows well the histories and statistics of the players.

She has delved into the business of baseball with the same keen intelligence that propelled her from switchboard operator at a Palm Springs bank at age 17 to Security Pacific’s 13th female vice president at 32. It was in that job, handling the accounts of the Gene Autry Hotel in Palm Springs, that she met her husband, whose holdings also include four radio stations and five music-related businesses.

After 10 years, Jackie Autry still listens, but she is no longer silent.

“When she came into the organization, she shut her mouth and listened and learned,” said Brown, who was named president last Nov. 1 but has been associated with the club since 1981. “As soon as she opened her mouth, the things that came out were very intelligent, both in broadcasting and baseball. She really became a student of operations. I can tell you now she’s a good baseball person and a good broadcast person. It didn’t happen overnight.”

Brown, a lawyer by training who acknowledges that he is not a baseball expert, says he is “trying to follow in her footsteps.” His realization that she had become an expert came about four years ago, when she was pronounced knowledgeable by such men as Mauch and Preston Gomez, a member of the organization and a former major league manager.

While her role in the control of the Autrys’ holdings has increased, Jackie Autry’s public profile has remained low. No biography of her appears in the team media guide, despite the widespread acknowledgement of the power she wields.

Perhaps her most visible involvement with the Angels is literally invisible, the two or so times a year she is a guest on the Angels’ radio call-in show on the Autrys’ KMPC, fielding fans’ questions and second-guesses about the team. The callers typically seem to express a genuine appreciation that she has taken the time to listen. But at times when the team is going bad, she grants, they can be “hostile, to say the least.” Her answers are forthright, and even incendiary. On occasion, her remarks have stirred impassioned debate.

“I try to accommodate them,” she said. “I know they have concerns and feel sometimes they’re not answered as straightforwardly as they’d like. I try not to deceive the listeners if I can.”

Early this season, after she defended, during the pregame show, the club’s decision not to re-sign 40-year-old fan favorite Brian Downing, the fans raised the topic again on “Angel Talk” after the game. The phones lit up; one of the callers was Jackie Autry, who had been listening as she drove the couple’s white Mercedes on the long trip home from Anaheim to Studio City.

Angels employees no longer are certain whether she should be called the owner’s wife or the co-owner, but they are clear that the only difference is whichever term she prefers. Employees are also careful to assert that Gene Autry is still in charge and has final say on everything.

“She defers to Gene,” Brown said. “I have never seen her override his decision.”

But Brown’s rise to the presidency from legal counsel and board member is as clear a sign as any that Jackie Autry is steering the club’s future.

He was brought on, with Gene Autry’s approval but at Jackie Autry’s behest, as part of a commitment to curb the organization’s losses and to eschew high-priced free agents in favor of strengthening the scouting and minor league organizations and relying on home-grown players.

“That was the resolve I had when I hired Rich Brown to come in as president of this company,” she said.

She and Brown say the club will lose a minimum of $2 million this year, and Brown said that figure could reach $4 million. The players’ union, the Major League Baseball Players Assn., traditionally disputes ownership’s claims of losses because owners do not allow access to the books. But recent indications such as the financial troubles of Seattle Mariners owner Jeff Smulyan despite record attendance there, the lack of a buyer for the Houston Astros franchise, and the Minnesota Twins’ projection that the club might lose $5 million, indicate that this time owners might not be crying wolf.

The situation only stands to get worse as salaries continue to escalate because of free agency and arbitration and with a substantial cut in television revenue expected after the 1994 expiration of CBS’ $1-billion contract, universally acknowledged to be a bust for CBS.

The Angels’ situation is not rosy. They face the prospect of free-agent bidding after this season for such integral players as Joyner, Schofield and McCaskill, a starting pitcher.

“If we try to retain all of our young men that are going to be free agents in the off-season, and try to deal with arbitration as well, we’re going to be losing $8 million to $10 million next year,” Jackie Autry said. “Gene has said, ‘I refuse to raise ticket prices again.’ Well, now you’ve got a problem.”

She says player salaries, not owners’ greed, threaten to price some fans out of the ballpark. She also doesn’t understand why players would move their families to “a lousy city” to play for “some owner they don’t care about,” for an extra $500,000 in salary.

“What can you do with $3 million that you can’t do with $2.5 million a year?” she said.

“As far as I’m concerned, the players can have all the money, all the revenues that come into this company,” she said. “They can have all of them. I just don’t want to lose money. It would be nice to also have some type of return on our investment.”

The banker in her was astounded, she said, when the club went to the American League Championship Series in 1982, and even then barely turned a profit, making $85,000 for the year, she said.

“I was fascinated. I said, ‘How does this happen? This doesn’t make sense to me.’ Even if the ballclub was worth $10 million, you would still expect to make more than $85,000.”

Winning a World Series, she said, is not necessarily the answer to a baseball team’s financial woes.

“If an owner says, ‘I want to go for it all and I’m willing to lose $10 million,’ and if he goes to the playoffs or World Series, what has he got? Because you still lose money because you can’t make that kind of money back by going to the playoffs or World Series.”

It is suggested that many owners would gladly write a $10-million check for the experience of seeing their team in the World Series, but Jackie Autry will have none of it.

“Why? It’s irresponsible,” she said. “It’s not the banker in me. It’s irresponsible.

Baseball, she believes, is facing a financial crisis, with owners’ other assets being hit by the economy as well.

“Everybody wants a winner. Everybody. I can’t think of one owner that doesn’t want a winner. But if winning means that the fans are going to be priced out of the ballpark, if winning means that owners are going to have to file for bankruptcy, then I don’t see that there’s any way.”

If Gene Autry indeed refuses to raise ticket prices for the second year in a row, the club might have to choose between losing money and forfeiting short-term competitiveness.

Jackie Autry said she is willing to make a stand.

“At some point in time, the fan has to understand that if they want to continue to come to this ballpark, or any ballpark in the country, that the owners have to say, ‘Enough. Had enough. Can’t go this way, because now a little kid can’t afford to spend $15 or $20 to get into general admission.’

“Basketball has now excluded the kids because of the ticket pricing. Football has excluded kids because of the ticket pricing, hockey the same thing. And again, this is supposed to be America’s pastime.”

It is not lost on Jackie Autry that if the Angels make a stand on salaries and allow some of their free-agents-to-be to leave, the very goal that has driven the club’s philosophy might be hampered. Gene Autry has done his part; would the Angels turn away from the goal now?

Jackie Autry said management is prepared.

“Even to the point, if it means we have to rebuild this club,” she said. “I know a lot of people are concerned because of Gene’s age. Gene looks at his age. He wants a World Series winner for Southern California. But he also cares more about the game than he does about himself. And I would say that he’s one of the few owners who probably does care more about the game than he does himself.”

As for next year, the plan is set.

“The only thing we are going to be asking of our people next year is to try to put a competitive club on the field, not lose money, and we are going to start building our farm system,” she said.

“This is a philosophy I had espoused since 1983 when we got total ownership of the club back from the Signal Cos. (a minority owner). And I firmly believe that every club that has ever been successful has built from within. Minor league system, strong scouting system, and filling in with minor trades when they needed to. The free agency market for most clubs has never worked. You look at Pittsburgh, you look at Cincinnati (National League champions) last year. They did it all through their farm system and some minor trades.”

Though her feelings toward the players’ union and salary escalation are antagonistic, Jackie Autry speaks with fondness and pride of the Angels players individually, saying, “I don’t think there is a player on this team that Gene and I don’t like.”

But if it sounds as if the Autrys have soured on the baseball business, it is partly so. They are frequently approached with inquiries about selling the team. They have resisted, so far.

“I know it has passed through Gene’s mind periodically because he’s very discouraged, but not because of the losing,” she said. “He’s very discouraged by the lack of caring or the lack of sensitivity by the ballplayers. You know, you pay a ballplayer $3 million and they don’t feel like they have the time to talk to you. I mean, if you ever treated your employer that way you’d be sitting out in the street.

“I know one year we tried to retain the services of a ballplayer, and we really wanted to keep him, and we were unsuccessful in getting him to attend any of the meetings with our general manager. So Gene left three messages at his home with his wife, and the man never had the courtesy or the decency to call back. Now here’s a man who at that particular time was making a great deal of money. Gene felt very hurt by the fact that this man didn’t even have the decency to pick up the phone and return his call.

“It’s not only that he’s Gene Autry and he deserves that courtesy just because of who he is. It’s just human courtesy to say, ‘Boss, I hear you called. Sorry I didn’t getback with you sooner. If you want to talk about contracts, I would rather not.’ From then on, I was astounded they could be so heartless.”

There is also the question of whether Jackie Autry would want to continue the quest for a World Series should she inherit the club.

“I would like to if we could get salaries in line with revenues,” she said. “As I say, I have no desire to go back to work at $50,000 or $60,000, or whatever they’re paying bank vice presidents now.”

She is in part being coy; the Autrys surely are in no danger of going under. The value of the franchise, for which he essentially paid $2.45 million in 1961, has soared, and is probably worth considerably more than the $120-million asking price for the Baltimore Orioles.

Baseball, more than many other businesses, draws its owners into the daily ups and downs, and Jackie Autry says that when the losses on the field mount, the couple suffer.

“I have to drive that Santa Ana Freeway every day for an hour and a half to get down here,” she said. “And that drive (after a loss), instead of being 50 minutes to get back home, seems like three hours.”

The Cowboy has been enjoying the victories and enduring the losses for 20 years longer than she has. But Jackie Autry said the one who agonizes most is the one in the driver’s seat.

“I take it much worse than he does,” she said. “I’m a very competitive person. I don’t like to lose. It’s not part of my emotional makeup to lose.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.