She Worship: Return of the Great Goddess : Beliefs: To some, it’s an offshoot of feminism, an attempt to apply women’s rights to spiritual life, witchcraft, nature worship. Binding it all is female divinity.

Lunea Weatherstone’s spiritual turnaround started with a bad back. She went to see a massage therapist, who considered Weatherstone’s spinal woes before saying something that left Weatherstone completely aghast.

Close your eyes, the therapist instructed, and try to envision “breathing God into the pain.”

That sounded too totally bizarre, so Weatherstone begged off. But the masseuse gently persisted. Imagine, she said, the most sacred image you can, and breathe that.

Weatherstone pictured the moon.

“I said, ‘That’s weird,’ ” Weatherstone recalls, lo these 10 years later. “She said, ‘No, that’s the goddess.’ ”

The Great Goddess, the female deity who devotees say reigned over people’s souls in prehistoric times, is making a comeback in the spiritual lives and academic thought of feminists across the country.

She’s calling on her ecology-minded followers to worship her ancient bailiwick, the Earth, in rites that celebrate the seasons and stages of life. She has inspired her own lunar calendars, Tarot decks, magazines and cable television show. She has prompted women to change their names to things celestial--Star and Lunea, to mention a couple. She has even brought forth chocolate goddess cookies, shaped like the earliest-known goddess statuary, the Venus of Willendorf (the original dates from about 30,000 BC, but her tasty imposters can still be had from an Upstate New York bakery for $9 a pound).

While goddess followers are generally resurrecting a female-centered form of pagan worship, the oft-used term “goddess movement” is something of a misnomer. Its adherents aren’t organized. There is no one way to commune with the goddess, no coherent doctrine to which everyone subscribes; rather, there’s a smorgasbord of beliefs and rituals from which worshipers can pick and choose.

For some women--and fewer men who are sympathetic to them--goddess worship represents an offshoot of feminism, an attempt to apply women’s rights to spiritual life. For some, it offers purpose behind the practice of witchcraft, or Wicca (Old English for witch ), a form of nature worship that has long been popular in alternative circles.

The ceremonial brew may be seasoned with Native American rituals or invoke the names of goddesses who ruled over the ancient worlds of Greece, Rome and Egypt. Not surprisingly, there is considerable overlap between the goddess movement and the forces of New Age.

But the one thread running through all these practices is the celebration of what is considered female divinity, embodied by Mother Earth whose seasons mirror the distinctly feminine powers of reproduction in their own cycles of birth and death.

This view has been spurred on by the recent work of feminist scholars, led off by UCLA’s eminent but controversial archeologist Marija Gimbutas, whose 1974 “The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe” inspired a raft of other authors. These academics have been exploring theories about neolithic Europe where, they say, peace reigned, men and women were equal, women were priestesses and pagan goddess worship prevailed.

Estimates of goddess worshipers run as high as 100,000 coast to coast. In Southern California alone, there may be as many as a couple of thousand, goddess followers estimate.

Witchcraft is the most popular form of goddess veneration in Southern California, favored for its raft of rituals that lend structure and ceremony to goddess worship. Witches cluster under new moons and gather to celebrate the changing seasons, the equinoxes and solstices as well as points in between that are considered sacred.

On the goddess calendar, holy days are likened to a woman’s life cycle. Take the day most popularly associated with witches, Halloween, a day dedicated to the Crone Goddess (representing a woman’s mature years), who presides over the Feast of the Dead.

Honoring the Crone, however, is a pray-as-you go affair. In “Women’s Rituals,” for example, author Barbara Walker suggests witches use the evening to honor the lives and work of women who are dead “as an antidote to patriarchal history that seldom notices them.” Although Walker also suggests cooking up a witches’ brew in a black caldron, witches commonly deny any connection to satanism, branding it as a bad rap imposed on goddess paganism by its Christian opponents.

“No true witches today practice human sacrifice, torture, or any form of ritual murder,” San Francisco witch Starhawk writes in her how-to book of goddess rituals, “The Spiral Dance.”

“Anyone who does is not a witch, but a psychopath. The world view of witchcraft is, above all, one that values life.”

“The Spiral Dance” is a hot goddess title for Harper & Row, a prime publisher of books about the goddess movement with 34 titles. Harper & Row spokeswoman Jo Beaton says the company has been clocking a steadily growing interest in goddess and witchcraft titles despite little or no promotion. The 10th edition of “The Spiral Dance,” for example, had already sold 13,000 copies by the end of June, four times its entire first-year total.

Starhawk says she based her book on oral tradition but embroidered it with her own stabs at trial and error in performing rituals. The book offers ceremonies for the waxing and waning of the seasons and spells for loneliness and anger. To create a “sacred space” that sets the stage for worship, she prescribes poetry and imagination: “Quicksilver messenger/Master of the crossroads/Springtime step lightly/Into my mind/Golden One whisper/Airy ferryman/Sail from the East on the wings of the wind.”

Lisa Hill, 36, a leader of a recently disbanded Costa Mesa goddess group called Women’s Spirit Rising, has a “temple room” in her Costa Mesa apartment, where she keeps an altar and her “sacred tools”--a rattle, a medicine shield, goddess figurines, crystals, cowrie shells (favored for their similarity to female anatomy) and horsehair.

Goddess rituals can, however, take celebration of womanhood to degrees that may be hard for some women to swallow. Starhawk, for example, offers a “Spell to be Friends With Your Womb” that invites women to light a red candle, face south and “with the third finger of your left hand, rub a few drops of your menstrual blood on the candle.” And the now-disbanded Costa Mesa group had been building a “moon lodge” where menstruating women were called on to record their dreams.

Goddess worshipers are acutely aware of how odd some of their practices may seem to outsiders, and it isn’t uncommon for them to shield their rituals from public scrutiny.

“It’s hard not to have something look ridiculous because it really does challenge fundamental beliefs and ideas,” says sociologist Judith Auerbach, former director of the University of Southern California’s Institute for the Study of Women and Men, an interdisciplinary center for research into ways that gender makes an impact on various aspects of society.

“But why is praying to some Goddess of the North any less compelling than the Father, Son and the Holy Ghost, than being told some water is holy water?” she asks. “How much of this is that it’s not what we’ve been comfortable with for the past thousand years?”

Pat Reif, chair of the master’s degree program in Christian feminist spirituality at Immaculate Heart College Center, says practicing Christians are divided on the subject of the goddess movement. “The hierarchy of the church would be very opposed. They would see it as a resurgence of paganism, the new paganism,” she says. “But a lot of Christian feminists would say, ‘Hey, wait a minute. Is it really dangerous?’

“What (goddess followers) emphasize is that we find the goddess within ourselves, which is not all that different from what Christianity taught me from the beginning, namely that I find God in myself. From that perspective, there’s no conflict, except they imagine the divine in female form rather than male.”

But women who acknowledge practicing witchcraft can pay for their candor. Consequently, many take their beliefs underground.

“It’s like being gay,” says Weatherstone. “People are nervous when you’re around their kids because people associate it with being satanic. They’re afraid you’re going to take their kids and go straight to hell.”

Auerbach doubts goddess worship will ever touch as many women as the nitty-gritty economic and family issues of the women’s movement have done.

“I think people will find it just too strange. This raises too many thorny issues. Our cultural lives are too constructed around patriarchal notions that a lot of women don’t see. The key to this whole story is capitalism. So long as we retain this system based on competitiveness and hierarchy, we’re not going to adopt any kind of movement, spiritual or cultural or moral, that challenges those assumptions.”

Still, for some, goddess worship is emerging as the latest wave in the evolution of women’s rights. If feminism first took on economic issues in the 1960s and ‘70s, and then moved on to questions about family life in the ‘80s, then the ‘90s are seeing women grappling with an even more elusive target--the soul.

“Part of the reason the goddess movement is so attractive is we’re at a point in the feminist movement where we’ve attended to other things and we’re only now attending to our spiritual life,” Auerbach says.

These days, Auerbach says, the major religions are coming under feminist scrutiny not only by goddess worshipers but also by women of the Catholic, Jewish and Protestant faiths. Goddess followers are challenging basic issues of religious equality, questioning male-oriented rituals, hierarchies and traditions.

“The big religions--Judaism, Christianity, Catholicism, even Buddhism and Hinduism--are patriarchal,” she says. “The clergy is male. The people most celebrated are male. Now there are women rabbis and you can have a bat mitzvah, but there are no altar girls in Catholicism and nuns are in the background. They don’t officiate. Generally speaking, it’s a male hierarchy.”

While some feminists are trying to forge change from within their inherited faiths, goddess worshipers may graft new beliefs onto their heritage or opt out altogether.

“I was raised a Catholic, and I had difficulty buying that God created everything,” says Hill. “It made more sense that a female energy would give birth.”

“I always believed that women and men were spiritually equal,” says Charles Sherman, 43, a Jewish artist from Beverly Hills who helped organize an arts festival two years ago called Goddess Project L.A. “I didn’t believe men were more spiritually evolved.”

Such sentiments are fueled by recent feminist scholarship, particularly Gimbutas’ hotly debated work.

Gimbutas, 69, has stirred controversy in academic circles with her theories, based on archeological finds in Greece and Yugoslavia, that the Judeo-Christian world was predated by peaceful, nature-loving cultures that worshipped various female deities and fostered harmony between the sexes. Gimbutas says those earlier matrilineal civilizations of southeastern Europe succumbed to marauding Indo-Europeans, who swept out of the Russian steppes in 4,400 BC and decimated goddess culture. She concludes that their aggressive legacy permeates Western culture to this day and that contemporary society would do well to learn from the egalitarian values of Old Europe.

“We need a holistic approach to life, more harmony between nature and human beings, a return to Earth, respect (for) our Mother Earth,” she says.

Gimbutas’ work has come under fire from academics who argue that evidence is scanty supporting her assertions that warmongers crushed the peaceful societies of Old Europe, that women were as prominent as Gimbutas says or even that ancient Europe was harmonious.

“These scholars have not read my book,” counters Gimbutas, adding that her theories are more fully developed in an as-yet unpublished book titled, “Goddess Civilization, the Neolithic Cultures of Europe Before the Patriarchy.” That book will cite Indo-European linguistic studies to buttress her theories that the people of the Steppes vanquished matrilineal society in Old Europe, she says.

Gimbutas’ findings have been hailed by some feminists who find in them vindication for their own views. And her work has inspired other authors, such as Carmel attorney Riane Eisler, whose 1987 “The Chalice and the Blade,” a mainstay of women’s studies courses, went on to divide civilization broadly into male “dominator” societies and female “partnership” cultures imbued with goddess worship and nurturing values. Eisler, who considers today’s “blade” to be the nuclear bomb, argues that the Earth’s survival depends on a return to a partnership society.

“We can generally learn that something better is a possibility for us,” Eisler says. “To these people, what we are doing to the planet today would not only seem stupid and suicidal, it would seem sacrilegious. Secondly, there are indications that the idea that sex is dirty and sinful and that women’s bodies are to be used and abused would be sacrilegious to these people. This whole dominator model has embittered our lives both as women and men.”

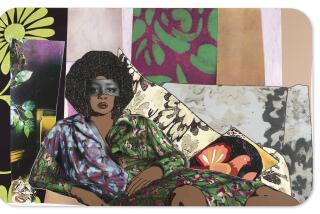

In an episode of the sporadic local public-access cable television show “The Goddess in Art,” hostess Starr Goode interviewed Eisler about why silence may have descended on goddess worship and the supposed existence of partnership cultures.

“What’s the cover-up here?” said Goode with a smile. “Is this Goddess-gate?”

Goode was also one of the organizers behind Goddess Project L.A., a monthlong series of poetry readings, lectures, art performances and celebrations, such as a cathartic day event called “A Therapy of Ecstasy,” which invited devotees to “celebrate the goddess by dancing your madness!”

“The goddess movement is so non-threatening,” says Weatherstone, a Long Beach witch who also edits a goddess magazine called Sage Woman. “You’re in the arms of the Mother. I think people need that comfort.”