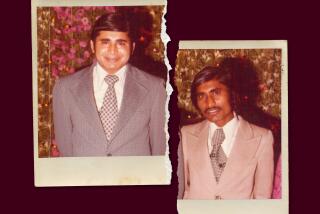

Marciano Brothers’ Time of Trial : Fashion: The four men who built Guess are a story of immigrant success. But their image has taken a severe beating amid a nasty war in the rag trade.

As boys growing up in the ‘50s, the Marciano brothers shared a cot in the kitchen of the Marseille synagogue where their father was the rabbi. Like stock characters in the movies of their youth, they were street urchins with hearts of gold--savvy, intensely close, in a rush to succeed, but always home Friday nights for Sabbath dinner.

Today, Georges, Maurice, Paul and Armand Marciano are huge successes, the founders and 50% owners of Guess, one of the garment industry’s most phenomenal triumphs of the 1980s. Their hands-on management has turned $170,000 scraped together from the leavings of bad real estate deals into a fashion empire that last year sold $500 million in blue jeans, men’s and women’s casual wear, swimsuits, shoes, watches, eyeglasses and children’s clothing.

The brothers still live within a few blocks of one another, only now in grand homes in Beverly Hills. The fruits of their commercial genius surround them: costly artwork, expensive cars, a new 14 1/2-acre headquarters in downtown Los Angeles, a growing chain of MGA retail stores soon to be renamed Guess, a “Marciano Pizza” at Spago.

And so inseparable are the Marcianos--the joke was the brothers never could marry, they were so tight--that when their parents are in town, they still share Sabbath dinner.

If not for one very bad decision, there the brothers’ tale would rest, an only-in-America fable of immigrant achievement.

The error was that in July, 1983, barely 18 months after they founded Guess, the Marcianos--eager for the capital and business know-how that could help their already hot company explode--sold a half-interest in Guess to the Nakash brothers (Joe, Avi and Ralph), the Israeli-born owners of Jordache, a much bigger jeans maker.

Within six months, the partnership was foundering; within a year, the families were at total war.

The Nakashes say the Marcianos tried to provoke a break, having developed seller’s remorse when they realized that the stake they had sold for just under $5 million was worth many times more. (Guess profits over the past four years have averaged about $45 million annually.) The Marcianos say the Nakashes tricked them into the sale, having intended all along to make off with Guess designs for Jordache, whose success was fading.

A jury in Los Angeles County Superior Court sided last year with the Marcianos, finding that the Nakashes had defrauded their partners from the start. In a trial scheduled to begin this week, another jury will determine what damages, if any, the Nakashes owe the Marcianos. Ultimately, the Marcianos hope, a judge will restore their 100% ownership of Guess.

Even if the Marcianos get everything that they want in court, though, their six-year dogfight with Jordache will have been won at great cost. And not just the $25 million or more that the Marcianos have paid in legal fees, or the $10 million that they have promised Los Angeles attorney Marshall B. Grossman if he forces the Nakashes out of Guess.

For in the course of this rag war, the Marcianos’ silken image has frayed, as allegations about their conduct before and after starting Guess have come to light:

- Their own investigators, hired to prove that the Nakashes’ agents planted false information about the Marcianos in French police files, concluded instead that the Marcianos were considered “commercial criminals” by French law enforcement.

French records obtained by the Marcianos say none of the brothers was ever convicted of a crime; the brothers say their private eyes were turned against them by Jordache’s sleuths.

- A former Superior Court judge, named to the Guess board to break ties and investigate the Nakashes’ charges of misconduct, found that the Marcianos had schemed repeatedly to divert Guess funds. The Marcianos, for instance, collected nearly $1 million in kickbacks from Guess contractors, the judge said.

The Marcianos have acknowledged that they wanted to draw more money from Guess than their agreement with the Nakashes allowed. But they insist that their conduct of the business was cleared with lawyers and accountants. The judge said the schemes did not demonstrate “bad faith or fraudulent intent.”

- A congressional subcommittee declared in public hearings last summer that the Marcianos had exerted “improper influence” over the Los Angeles office of the Internal Revenue Service. The Marcianos deny any wrongdoing. Half a dozen federal agencies are said to have probed the actions of Octavio Pena, the Nakashes’ chief investigator, who assisted the subcommittee.

- Most damaging, potentially, is that a federal grand jury in Los Angeles has been investigating alleged tax evasion by the Marcianos. The Marcianos’ lawyers say it appears that the probe has been closed. Pena says the brothers may soon be charged. The prosecutor in the case won’t comment.

So for the Marcianos--by turns charming and moody, generous and ruthless--the taste of success is bittersweet.

“The pleasure is stolen. The feeling of accomplishment is spoiled,” conceded Paul Marciano, at 37 the youngest and most combative brother and the creator of Guess’ trend-setting advertisements. “I really have the feeling of a waste of five years.”

North African Roots

They were born in North Africa--Armand, the eldest, in Morocco, the others in post-war Algeria. As French colonialism ebbed, their father, a third-generation rabbi, was recalled to France and assigned to the synagogue in Marseille, a big, rough, gaudy port city on the Mediterranean.

It was la vie active , the hectic life of the businessman, that attracted the brothers, especially Georges. In his 20s, he was on his own, making neckties and peddling them to a few shops. Early on, Maurice quit medical school to work with Georges. And when a men’s peasant shirt that Georges designed proved popular, Armand, an assistant bookkeeper, and Paul, a store clerk, left their jobs to help, too.

They manufactured ties and shirts, started a retail outlet and shared an apartment behind it. In Bandol, 50 miles eastward up the Cote d’Azur, they opened their first women’s shop, named MGA, in an old fish store that never quite lost its stink.

By the late ‘70s, they were manufacturing casual wear, including blue jeans, and operating a string of 20 little shops along the Cote d’Azur. But a trip to Los Angeles in 1977 gave the Marcianos new ideas. Intending to visit for a week, Maurice, Georges and Paul stayed for two months, opening an MGA in Century City before returning to France with plans to move permanently to Southern California.

Their affairs in France did not tie up smoothly, though. Exhibiting a stubbornness their parents describe as a family characteristic, the brothers refused to pay a corporate tax bill that mounted by 1981 to 60 million francs, or about $11 million. (The Marcianos paid $2.25 million to settle the debt in 1986, according to Paul.)

Paul insists that the tax dispute was the only blemish on the family’s record in France. But American officials--their interest fanned by the Nakash forces--have suspected otherwise.

As part of investigations by the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles and the Immigration and Naturalization Service, European-based INS agents compiled a “rap sheet” of purported offenses by the Marcianos. According to a copy of the document made public in the trial last year, the agents had information that Armand, Georges and Paul, between 1973 and 1982, engaged in stealing, fraud and counterfeiting and used explosives. Maurice’s record was clear.

One of the listed offenses was Georges’ supposed arrest in July, 1982, for attempting to blow up a family home near Marseilles. Acting on that information, the INS accused him in August, 1988, of having lied years earlier when he said, in an application for permanent resident status, that he had never been arrested. If the agents were right, Georges could have faced deportation.

The news arrived as family members gathered for the brit milah , the ritual circumcision, of Georges’ newborn son Scott. Then, as now, the Marcianos vehemently insisted that none of them ever had been arrested for or convicted of any crime. Letters from high-ranking French law enforcement officials backed up their claim.

Indeed, after a month of furious lobbying, the INS dropped its attempt to revoke Georges’ legal status. Fifteen months later, according to a Justice Department spokesman, the INS is reviewing its handling of the incident.

The Marcianos say they know what happened. They have filed a federal racketeering lawsuit charging that Pena, until recently the Nakashes’ investigator, planted false information about them with American officials in Europe, then schemed to have Georges deported so he would be unavailable to testify in the 1989 Marciano-Nakash trial in Los Angeles. Pena denies it.

To prove their charges, the Marcianos hired private eyes last summer to retrace the steps of Pena and his associates. Connecticut investigator John Quirk initially reported from Europe that there were signs that Pena had misled American agents, according to copies of his reports obtained by The Times.

But Quirk also began collecting information that the Marcianos were, in fact, well known to French law enforcement.

In a report last August, Quirk’s boss, Virginia investigator William Mulligan, confirmed that none of the Marcianos had ever been convicted of a crime. But he added that French records stated they had “trafficke(d) in jewelry and garments,” “broken customs laws” and “avoided taxes,” according to a report made public in the racketeering case.

Many of the allegations were civil in nature, Mulligan wrote. “The Marcianos are not considered dangerous criminals or men of the Mafia stripe,” he said. “They are viewed as commercial criminals.” Pena, he added, was “a catalyst” for Georges’ problems with the INS.

The Marcianos allege that Pena influenced Quirk to double-cross them. “It’s just crazy,” Quirk responds. “The records are there. They were not planted by Pena.” Quirk said he has copies of the French police records locked in a safe.

For the most part, others who have sought such records have been frustrated. This much, though, is certain about incidents listed on the INS rap sheet:

- There was an explosion at a home owned by the Marcianos’ uncle. At the time, the French press reported that while there were signs that it was an anti-Semitic attack, there were suspicions that the blast hid “racketeering practices.” Georges--who was not in France--never was charged in the case.

- Under questioning by French police in 1980, Paul Marciano admitted that he ordered the unauthorized printing of at least 1,400 shirts with pictures of Snoopy, the Peanuts cartoon character. A French civil court ordered a Marciano-owned store to pay cartoonist Charles M. Schulz and United Features Syndicate $2,600 for the counterfeiting.

Real Estate Casualties

Today, Guess ranks among the five most frequently counterfeited labels in apparel, its lawyers estimate. Around the world, they have filed literally hundreds of lawsuits to counter imitators.

But the Marcianos had not even imagined Guess back in 1979 and 1980, as they tried to establish themselves in Southern California.

Sharing a house again, this time in Beverly Hills, Georges, Maurice and Paul joined other refugees from high-tax, weak-currency nations who were creating a new cafe society on the Westside and building fortunes in a condominium price boom.

Only the boom went bust. Friends say the three brothers (Armand, with a wife and children, was still in France) lost much of the wealth that they’d brought with them. They began casting about for new ventures to complement the four MGA stores that they had opened.

“They were like a boat without water, and so they were going putt-putt, every direction,” remembers Max Baril, owner of the Beverly Pavilion and Beverly Rodeo hotels and one of the brothers’ first confidants in America. “It was only until the reality came that they had lost quite a bit of their capital (that) they said, ‘You know what? We’ve got to go back to fundamentals.’ ”

Renting a 700-square-foot office near the California Mart, center of Los Angeles’ garment industry, they hired a pattern maker and, in the fall of 1981, started the manufacturing enterprise that they ultimately called Guess.

The concept was simple but audacious: Make jeans like the ones women were wearing in St. Tropez, and persuade Americans to buy them for $50, $60, $70 or more.

And how it worked! One of the first jeans that Georges styled for Guess--tight, with zippers at the ankles, made of a stone-washed denim never before seen in the United States--flew out of Bloomingdale’s in New York. Paul, rebuffed by the other major fashion magazines, talked Michael Coady, publisher of W, into printing a $35,000, three-page, Guess ad and giving the fledgling firm 60 days to make the sales that would pay for it.

Denim had been dead, but Guess revived the market. “The timing was great,” said Ed Solomon, a Los Angeles fabric salesman who started out selling Guess 1,500 yards of denim every two weeks and remains one of its primary suppliers. “You’d go into the store, and everything looked the same. It was like Deadsville. And that market that they’re in, the high end of the fashion market, is always looking for something new.”

Guess was bigger than anything the Marcianos had done in France. Within a year, sales climbed to $12 million. Georges, since childhood the boys’ leader, thought that the brothers needed a partner. Maurice, in charge of day-to-day management, was reluctant to tie up with outsiders.

“We were doing well,” says Maurice, described by associates as the most mercurial of the brothers. “We didn’t need anything.”

The Marcianos began discussing a partnership with the Nakashes in April, 1983. The families differ over who courted whom. The Marcianos argued in trial last year that Jordache was in desperate straits and needed a source of new designs. The Nakashes insisted that Jordache was having its best year ever in 1983.

In any event, the deal was signed that July. The Nakashes paid the Marcianos $4,775,000 for 51% of Guess and half the seats on the company’s board. Maurice, Georges and Armand (by then in America) held the rest and got contracts to run Guess. The Nakashes were to run Gasoline, a division that sold lower-priced versions of Guess products.

“The Marcianos were enthused and almost flattered that a company like Jordache at the time would show an interest in them,” said Jeffrey Krinsk, hired away from Hang Ten soon after the deal to enlist licensees to manufacture new lines under the Guess name.

“We believe we find friends and partners . . . like almost brothers,” explained Paul. Brothers? Like Cain and Abel, the Marcianos would come to believe. “They stabbed us, six months later.”

Rocky Partnership

The partnership fared badly from the start. In December, 1983, the Marcianos filed suit for the first time to cancel the deal, alleging that the Nakashes had reneged on their promise to put Guess’ rather haphazard operations on a more professional course.

The case was settled a month later by making Guess a 50-50 partnership. Nonetheless, whatever trust there had been between the two families seemed to evaporate. Guess sales were doubling on almost a monthly basis. But at the same time, the Marcianos and Nakashes were accusing each other of scheming to steal from Guess, divert company funds or engage in underhanded competition.

The jury in last year’s trial heard extensive testimony about whether the Nakashes stole Guess and Gasoline designs and used them to make Jordache jeans. The jurors concluded that the Nakashes intended from the start to steal the Marcianos’ ideas. The trial beginning this week will determine what damages, if any, the Marcianos are due; afterward, Judge Norman L. Epstein of the Los Angeles County Superior Court will decide if the Nakashes must give up their stake in Guess.

Neither jury, however, will have heard the Nakashes’ charges against the Marcianos, which are set out in a countersuit in Superior Court and a separate federal lawsuit accusing the Marcianos of racketeering. Instead, those allegations have been sifted through by attorney Richard Schauer, a retired Superior Court judge whom Epstein appointed to the Guess board in 1985 to break deadlocks between the feuding partners.

According to internal Guess reports obtained by The Times and documents filed in court, Schauer found substance in a number of the Nakashes’ allegations.

During 1984, as the war between the families escalated, the Marcianos set up an elaborate kickback scheme that diverted to them just under $1 million in Guess funds, Schauer concluded. Guess raised the price that it paid sewing and laundry contractors, and the Marcianos required them to refund the increase to companies owned by the Marcianos whose only apparent function was to collect the kickbacks. Most of the diverted funds eventually were returned to Guess.

Repeatedly in 1984, Schauer found, the Marcianos--acting either out of ignorance or “subconscious self-interest,” as one of his reports put it--took steps that the Nakashes viewed as harmful to the company they jointly owned.

They sold thousands of damaged garments to Marciano-owned outlet stores for far less than such goods were sold to other customers, costing Guess $299,000 in profits, Schauer concluded. The Marcianos gave a company owned by Paul the right to use the name “Georges Marciano,” then set up a new line, “C.O.D. by Georges Marciano,” in competition with Guess. Georges and Paul also failed to disclose their co-ownership with Michel Benasra, a childhood friend, of the company that produced the Baby Guess line.

Even so, Schauer concluded that the Marcianos did not act in bad faith toward the Nakash brothers--a finding that has outraged the Nakashes, who complain that the ex-judge bent over backward to interpret events in a light favorable to the Marcianos. For now, Judge Epstein has declined to accept Schauer’s findings as a basis for resolving the Nakashes’ charges.

But the war has not been confined to the courtroom. For the Marcianos, it has been all-consuming--both because of the passion that they bring to the fight and because they and the Nakashes each have dragged the battle into many venues.

Perhaps the best analogy is to a very ugly divorce, where mud splatters on both sides.

Each family has accused the other of trying to extort a settlement of the dispute. Each has turned in the other to the Internal Revenue Service, charging tax evasion. The tax cases spawned grand jury investigations. In November, federal prosecutors informed Jordache and the Nakashes that they would not be charged. Prosecutors in Los Angeles won’t say if the probe of the Marcianos has ended.

Last summer, the tax matters prompted the most spectacular episode to date in the families’ blood feud.

Inspired by Pena, a subcommittee of the House Government Operations Committee probing IRS wrongdoing charged that the Marcianos had manipulated IRS criminal investigators in Los Angeles. By cozying up to top IRS officials, the subcommittee alleged, the brothers were able to instigate the Jordache investigation and a probe of Guess’ menswear licensee, whose contract they wanted to terminate. The Marcianos, as well as the IRS officials involved, denied any wrongdoing; some critics in the press adopted the Marcianos’ position that the subcommittee’s investigation was one-sided.

Associates say the dispute has taken a heavy toll on both families. “I really think everyone is miserable,” said Judith Brustman, a Los Angeles interior designer who has decorated homes for both the Nakashes and the Marcianos and showrooms for both Jordache and Guess. “The lawsuit really created chaos in all of their lives.”

Board meetings, not surprisingly, have been acrimonious. Current and former Guess employees have been called before grand juries; some have been battered by the process, left confused about which family, if either, has their interests at heart. Vendors and customers say dealing with Guess has been difficult during periods when the Marcianos were in depositions or in court.

“It’s really sad, because it’s been so counterproductive,” said Solomon, the fabric salesman. “They got preoccupied. It became an obsession.

“As successful as they are,” Solomon said of the Marcianos, “they probably could have been double the size by now.”

Booming Growth

How successful is Guess?

Financially, at 10% or better each year, its return on sales ranks with the best-performing publicly held apparel companies. The company’s dramatic growth has continued unabated. For Bloomingdale’s, the nation’s trend-setting department store, 1989 was “the best year with Guess we’ve had,” said Executive Vice President Russell Stravitz.

The Marcianos and outsiders fasten on two comparisons in gauging Guess’ progress--both flattering.

In jeans wear, some say Guess has become the “high-fashion Levi,” a company that shows the same lasting power and consistent quality that have made Levi Strauss & Co. thrive. Guess junior jeans--the company’s mainstay product line--are more popular among teen-agers and young women than Levi’s, Lee, Jordache or any other brand, according to a July survey by Seventeen magazine.

As a fashion merchandiser, a company pushing its brand name into new markets, Guess is compared to Ralph Lauren.

Like Lauren’s polo pony, Guess’ upside-down triangle appears on a range of products, from eyeglasses to shoes to a highly successful line of fashion watches--a list to be joined in March by a Guess perfume made by Revlon. And like Lauren, Guess has maintained tight controls on the quality of its name-brand products and their marketing.

“They certainly are bigger and ahead of where Calvin (Klein) and Ralph (Lauren) were at seven years,” said publisher Coady, who heads Women’s Wear Daily as well as W.

Georges Marciano’s fashion sense gets much of the credit. Though he does not design garments from scratch, his conservative tastes define Guess--a love of classic styles, good fit and rich fabrics.

Guess tries “to be very quality, very chic looking, but not trendy,” said Mike Levison, a veteran swim wear manufacturer in Tarzana who produces the Guess Swim line.

The Guess image is largely the product of magazine ads conceived by Paul. From dark and moody photo images of sensuous women to brighter views of real, wizened cowboys, the ads sell a brash, avant-garde attitude, rather than promote any particular Guess garment. They reflect the brothers’ baby boomer love affair with old movies and the American West.

“Guess ads are probably recognized by more people than any other ads in the fashion community,” said Richard Kinsler, publisher of Mademoiselle magazine.

Media Watch, a feminist group in Santa Cruz, has called for a boycott of Guess, charging that its ads demean women, intermingling sex with violence. Paul, acknowledging that some Guess ads went too far, has changed photographers and taken some of the sexual edge off recent campaigns.

Less visible, but no less critical to Guess’ growth, is the Marcianos’ unrelenting pace and management style. The brothers, at work as early as 7 a.m., delegate little. The four boys who shared a bed 30 years ago make every major decision--behind closed doors, speaking French.

Guess has kept most of its production in Los Angeles. Besides its own 1,000 workers, its contractors employ 6,000 to 7,000 more, making Guess one of the biggest forces in the local garment industry.

Domestic production has allowed the company to introduce new styles quickly--every six weeks, sometimes, instead of the traditional five times a year. Some contractors say Guess’ size also has allowed it to dictate terms that make it impossible for them to pay workers a decent wage, an allegation that Maurice disputes.

Guess’ own employees tell two stories.

White-collar workers feel like family, for better or worse. They suffer from the high-strung brothers’ emotional lows, but bask in the personal attention that the Marcianos pay to the business. Former production workers, meanwhile, complain about going years without a raise and being fired upon asking for one. Paul said he doubted their complaints were valid.

Bitter Conflict

Restaurant designer Barbara Lazaroff, sipping bottled water at Spago, the chic West Hollywood eatery that she and husband Wolfgang Puck own, describes the Marcianos--”the guys”--as “understated” and “down to earth.”

Their company, Lazaroff contends, “is culturally influential.” Their loyalty to friends, she says, is bottomless, describing how Paul pulled Guess advertising from Interview magazine after it slammed Spago in an article.

That same depth of feeling, according to Lazaroff, fuels the Marcianos fight with the Nakashes. “I can’t honestly believe anyone enjoys that tsurris in their life,” she says. Yet, “the one thing these guys would never do is give up.”

Both families agree on the outlines of a settlement. The Nakashes would give up their stake in Guess. The sides would split a frozen account, now worth $93 million, that represents the Nakashes’ accrued share of Guess profits for the past four years.

But the two sets of brothers are millions apart on how to divide those funds. And every settlement effort over the past six years has collapsed. Even rabbinic mediation--with the Marcianos’ father, Simon, and the Nakashes’ hand-picked rabbi guiding the discussions--went nowhere. Neither side is predicting an agreement soon.

So the spectacle continues, as bits and pieces of Guess’ bizarre story tumble into public view.

“If a jury heard all the facts in this case--I mean all the facts--I think they would say, ‘A pox on both your houses’ ” said Howard L. Weitzman, the Nakashes’ attorney. “And by the way, that’s probably the fairest result.”

THE BRAND-NAME DENIM LINEUP

Survey asked 1,055 women age 13-21 to list the different brands of jeans they own. Total adds up to more than 100% because in many cases the respondents own more than one brand. The survey was conducted in July, 1989.

Guess 48.2

Lee 35.3

Levi’s 33.1

Jordache 23.5

Gitano 19.9

Esprit 17.3

Bon Jour 15.6

The Gap 15.1

Calvin Klein 15.1

Chic 14.5

Bongo 14.2

Forenza 14.0

Zena 13.9

Union Bay 12.4

Cherokee 10.7

No Excuses 10.1

Sunset Blues 9.7

Bugle Boy 9.4

Palmettos 8.1

Wrangler 7.8

Benetton 6.6

Lawman 6.1

Liz Claiborne 5.9

Sasson 4.7

Pepe 4.5

Jou Jou 4.2

Soon 3.2

Rio 2.8

Limited Express 2.8

Jean Jer 2.6

Ralph Lauren 2.5

L.A. Gear 2.5

Girbaud 2.3

Corniche 2.1

Source: Seventeen magazine research department

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.