Samuel Beckett Dies at 83; ‘Godot’ Author, Nobelist

Samuel Beckett, the taciturn master of fiction and drama whose bleak poetic and darkly comedic works etched the pessimism of the human condition, has died in Paris, it was learned Tuesday.

Jerome Linden, his publisher, said the Nobel laureate was buried Tuesday in a Paris cemetery after his death last Friday of respiratory failure. He was 83 years old, and the news of his death was delayed in keeping with Beckett’s secretive life style.

The last of an illustrious line of 19th- and 20th-Century Irish literary titans who included playwrights J. M. Synge, Sean O’Casey and W. B. Yeats and novelist James Joyce, Beckett produced landmark works in both disciplines--the play “Waiting for Godot,” and a stark trilogy of novels, “Molloy,” “Malone Dies” and “The Unnameable.”

Those works and a sparse collection of other novels, plays and radio dramas eventually won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969. Typically disdaining any trace of celebrity, he ignored the ceremonies and sent a friend to collect his $72,800 check. Beckett also was given four Obie (off-Broadway) awards for his dramas and shared the 1961 International Publishers Award with Jorge Luis Borges.

He was buried in a private ceremony at Montparnasse Cemetery. Linden said Beckett had been living in a retirement home since moving out of his Left Bank apartment last summer after the death of his wife.

Beckett’s characters were stunted--beaten men and women doomed to successive miseries and compelled to crawl onward--not by any spark of optimism or courage, but rather by the simple fact that there is no alternative.

“Beckett is a prophet of negation and sterility,” wrote critic George Wellwarth. “He holds out no hope to humanity, only a picture of unrelieved blackness.”

Yet, in his finest works, Beckett couched his unending narrative of grimness in a prose style honed to icily elegant perfection, and he mocked the hopeless progressions of his tortuous plots and addled characters with the mordant humor of a prisoner laughing at his gallows.

“He was a man of great imagination. He was in a sense a quiet leader,” British playwright Harold Pinter told Independent Radio News after hearing of Beckett’s death. “He was in the forefront of modern literature. He was totally original and a man of great courage, not only in himself, but in his work. His work knew no bounds really. He didn’t accept any limitations.”

Epitomy of the Absurd

There seemed no end to the abuses Beckett heaped on the poor souls who populate his work. One lives in a trash can. Another is buried to her waist in sand. Others are in various states of bodily decay, some so lifeless that flies mistake them for corpses. Perhaps they are corpses.

In “Waiting for Godot,” a play often used to epitomize the theater of the absurd in college drama courses, the main characters, Vladmir and Estragon, bumble and feud while mysteriously rooted to a nameless wasteland, waiting in vain for Godot, a savior who never comes.

Despite the relentless despair that they embody, the two tramps bicker and prattle endlessly in roles that have attracted a legion of comic actors from Bert Lahr and Zero Mostel to Steve Martin and Robin Williams. In the only film project that Beckett ever wrote--called, appropriately enough for Beckett, “Film”--the unnamed, silent character was played by Buster Keaton.

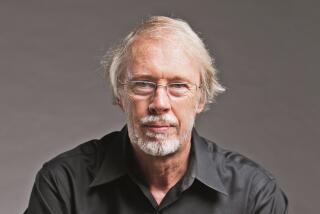

Beckett himself could have been a silent film actor. Hawk-faced with unflinching eyes and a stiff pompadour that seemed sculpted from metal, he stared out from his book jacket photographs in an enigmatic pose that telegraphed nothing.

Yet while he cloaked himself in silence, volunteering no opinions, no gossip and few explanations of the philosophy that governs his work, Beckett’s life offered surprising contrasts. The man who offered no hope turned out to be a Resistance fighter in France during World War II who narrowly escaped the Gestapo, secured country roads for advancing American troops and was awarded the Croix de Guerre.

Typically, his friends knew nothing of the honor until 1975, 30 years after the war’s end.

Samuel Barclay Beckett was born in Dublin, Ireland, son of a surveyor and an interpreter for the Irish Red Cross. But the date of his birth is clouded. He said he was born on Good Friday, April 13, 1906. But a biographer, Deirdre Bair, suggested he was really born a month earlier, with Beckett shifting the date to the anniversary of the Crucifixion as a boost to his legend.

He attended Portora Royal School, where Oscar Wilde was educated, and then attended Trinity College. There, according to legend, he angered school officials by printing a class paper on a roll of toilet paper.

From 1928 to 1932, he was a lecturer in English in Paris, the country he would call home for the rest of his life. In the early 1930s, Beckett aided James Joyce, then at the edge of blindness, by taking dictation and copying sections of Joyce’s final masterwork, “Finnegan’s Wake.”

Beckett traveled for several years in Europe before settling down finally in Paris in 1937 to an existence as interpreter and failed writer. That winter, according to Bair, he was stabbed near the heart by a pimp. Lying in a pool of blood on the sidewalk, Beckett was aided by a woman passing by. The woman, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, a pianist, called an ambulance and stayed with him for the rest of his life, becoming his wife. She died July 17 at age 89. They had no children.

Before the war, Beckett dabbled in prose, poetry and criticism, but it was not until the early 1940s that he turned fully to literature. While his wife supported him by sewing, Beckett’s earliest works met with repeated rejections from publishers. He considered becoming a pilot. He thought of working in films, but a letter sent to famed Russian director Sergei Eisenstein was never answered.

When the war intruded, Beckett ended his years of passivity and inaction. From 1940 to 1943, he fought with the Resistance. Under threat of capture, he fled to remote farmlands in southeast France where he alternated writing the chapters of his first novel with his secret war work.

Bair described him as he returned after a successful sortie with a group of Resistance fighters to the town of Rousillon. As they lustily sang the “Marseillaise,” Beckett followed, marching “without a rifle, his head bowed, grimly serious and silent.”

He pursued his craft in that way in the years following the war. From the mid-1940s until the late 1950s, he produced a torrent of work written in French--issuing novels, plays and short pieces from Paris without any accompanying interviews or explanations.

First there were two novels, “Molloy” (1947) and “Malone Dies” (1951). Each charted the futile progress of protagonists who moved about an anonymous, ruined countryside like pawns in a madman’s chess game.

Then, in 1952, Beckett published “Waiting for Godot.” Its plot was, on the surface, the barest of sequences. Two miserable clowns, Vladimir and Estragon, stand waiting for Godot. Growing impatient, they tell each other that should leave. They stay. They bicker. They whimper. They chatter. They are visited by a master, Pozzo, and his slave, Lucky. There is a second visit.

But in the end, Vladimir and Estragon are where they were at the start, motionless as if wedged into cement, still waiting for the faceless Godot.

The play stirred controversy during its initial run in Paris in 1953. It premiered in the United States in 1956, absurdly, at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in Miami Beach. The mostly elderly audiences were bewildered and the play quickly closed. It opened to marginally better reviews and slightly more appreciative audiences on Broadway.

Beckett refused to explain what lay beneath “Godot,” as he continued to do all his life. To one questioner who posed theories, he said: “I take no sides about that.” To another, he said: “I’m not interested in any system. I can’t see any trace of any system anywhere.”

Laboring to describe what Beckett refused to explain, critics and scholars fell over themselves to make sense out of “Godot.” It was like the seven blind men describing the elephant.

“ ‘Godot’ is a hymn to extol the moment when the mind swings off its hinges,” said drama critic Kenneth Allsop.

“The human predicament . . . is that of man living on the Saturday after the Friday of crucifixion,” said William R. Mueller and Josephine Jacobsen, “and not really knowing if all hope is dead or if the next day will bring the new life which has been promised.”

Said another critic: “It presents the view that man . . . brings his wonderful humanity . . . to the weird journey of existence.”

Stubborn Silence

Critic Bert O. States found at least two audiences who seemed appreciative. “Convicts and children love it,” he said.

From “Godot” onward, whatever Beckett’s message was became even more vague. In “Krapp’s Last Tape,” dialogue comes from tape recorders as well as actors. In another play, “What Where,” four men in skullcaps--named, as if an infernal doo-wop chorus, bam, bom bim and bem--speak in riddles to walls. In “Act Without Words,” Beckett banished words altogether and trapped his protagonist on-stage. When the actor tries to scurry off, an unseen presence pitches him back on.

Beckett remained stubbornly silent in his later years. He could be found in the same hotel lobbies and shops of the working-class Paris neighborhood where he had lived for decades. He only rarely consented to interviews. They were usually brief and pointless.

Behind his silence, he could be willful. When the American Repertory Theater played his “Endgame” in a subway tunnel instead of a bare room with two windows--as called for in his script--Beckett insisted that the play’s program contain a statement that the altered version was a “complete parody of the play.”

Beckett did not confine his anger to the manner in which his plays were produced. He continued to practice the behind-the-scenes activism that he showed as a Resistance fighter, often linking up with other artists to pressure for a variety of social causes. In 1976, for example, Beckett joined 49 other Nobel laureates in demanding the release of a Jewish activist imprisoned for eight years in the Soviet Union.

By the 1980s, the flow of work from his Paris apartment had slowed to a trickle, as it had been in the years before the war. It was as if Beckett had finally become one of his own characters--expressionless, passive, preparing for the end.

“Perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story,” he wrote in the final lines of “The Unnameable,” “before the door that opens on my story, that would surprise me, if it opens, it will be I, it will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

PLAYWRIGHT REMEMBERED

Beckett never changed, forcing us to see things his way. F14

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.