‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ : Scorsese Ends Long Quest to Film Kazantzakis’ Novel

It has been a tumultuous journey from book to screen for “The Last Temptation of Christ.”

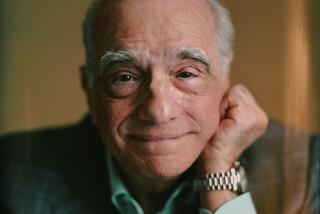

The journey ended with director Martin Scorsese realizing a 15-year quest to film Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel.

But it didn’t start with Scorsese.

In the early ‘70s, Sidney Lumet quietly acquired rights to the novel from Kazantzakis’ widow. In the spring of 1971, Lumet announced that he hoped to begin filming “The Last Temptation” in September of that year, in Israel.

But Lumet never got around to casting. Nor did the project make the studio rounds. The reason, Lumet recalled this week: “I never could lick it in terms of a screenplay. . . . And I just couldn’t pull it off.”

Especially challenging, he said, was the book’s depiction of Judas as a kind of heroic fall-guy who is hand-picked by Christ as the one who will seal his fate.

“They set it up between them to fulfill the prophesy,” said Lumet. “To me, that was what made the project so unusual.”

But what about the much talked-about, widely protested fantasy sequence--in the book and the Scorsese film--which finds Christ coming off the cross and living life as a normal man, complete with marriage and fatherhood?

“I really don’t understand what the fuss is about,” Lumet said. “That is a total fantasy--which is also the heart of the book. To film the book, which I find to be deeply religious, you have to examine Christ living as a normal man.

“Centuries of paintings have deviated from the Gospels,” Lumet said, “so I guess I’m rather amazed by all the controversy that the movie has generated.”

At about the same time that Lumet was attempting to write a script for “The Last Temptation”--with off-Broadway playwright Seymour Simckes--Scorsese was at work directing “Boxcar Bertha.” Leading lady Barbara Hershey--later to become Scorsese’s Mary Magdalene--introduced him to the Kazantzakis novel.

More than 10 years later--in February, 1983--it was announced that Scorsese would film “The Last Temptation of Christ,” based on a script by Paul Schrader (who wrote Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” and co-wrote his “Raging Bull”).

“I plan to show Jesus the man and not the God . . . a man who wrestles and struggles with his temptations and whose faith stands up to this superior test,” Scorsese told the Hollywood Reporter.

Producers would be Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler--producers of Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” and “New York, New York.”

Months later, Paramount Pictures became involved--after extensive contractual negotiations, and concerns over a script that was deemed “too dark.”

By then, both Robert De Niro and Eric Roberts had turned down the role of Christ. Christopher Walken was briefly named to the part--but Paramount rejected the casting. There was even gossip column banter about Sylvester Stallone playing the Savior.

Then producers Chartoff and Winkler exited. In December, 1983, John Avnet came aboard. Filming was set to begin Jan. 23, 1984, in Israel. About 100 rooms were booked for cast and crew at the Laguna Dan Hotel in the Red Sea resort of Eilat.

Harvey Keitel would be Judas, Hershey would be Magdalene, rock star Sting would be Pontius Pilate. Cast as Christ was the then-unknown Aidan Quinn. (But he was being talked about as the star of his first film--the teen Angst tale “Reckless.”)

Sets were constructed. Pre-production was nearly complete. But after spending $2 million to $3 million, the Paramount regime (at the time) of Barry Diller, Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg had a change of heart. Less than a month before shooting was set to begin, the studio pulled the plug.

Religious fundamentalists had charged that the project was blasphemous, and deluged the studio with letters condemning the movie.

Scorsese later told the Washington Post: “In a way, living in Hollywood at the time was like living in a Kafka world. . . . Katzenberg would tell me, ‘Listen, Marty, I just want you to know, Michael Eisner really wants this film made.’ And then a week later, Eisner would say, ‘Katzenberg is the one who’s really behind this picture.’ And then I’d hear, ‘Barry Diller is really behind you on this point. He wants this picture finished, he wants it done.’ And then I’d hear, ‘The only friend you have here is Michael Eisner.’ Every day, every half-hour, it would change.”

Paramount put “The Last Temptation” into turn-around--which means it was up for grabs to any studio willing to foot the then-reported $12-million budget.

Universal Pictures and Warner Bros. each considered the project--and turned it down. New World Pictures, Hemdale and Carolco also toyed with making the movie.

In the fall of 1984, it looked as if Europeans would save the day.

French culture minister Jack Lang promised a $300,000 “production aid subsidy” if the film would shoot in Europe or North Africa with a French producer. (Plans still called for an English-language film with a largely American cast.)

But the offer was ultimately withdrawn--following pressure by concerned European religious figures, including the Archbishop of Paris. Among the headline-making--but false--reports: Scorsese’s Christ would be homosexual.

The project was put off again . . . until Universal’s announcement in the fall of 1987 that, as part of a long-term, multiple-film agreement with Scorsese, it would distribute “The Last Temptation.”

Thomas Pollock, chairman of the motion picture group for MCA--parent company of Universal--told Daily Variety: “We are open to whatever is attractive to him (Scorsese) and to us and will work with him to get it made.”

“The Last Temptation” went into production on a strictly closed set in Morocco in October, 1987, with Willem Dafoe as Christ. Keitel and Hershey were (again) Judas and Magdalene. Sting bowed out of the role of Pilate; David Bowie bowed in.

Barbara De Fina--production manager on “The King of Comedy,” co-producer of “The Color of Money” and Scorsese’s wife--produced.

But the film would not shoot under the title “The Last Temptation.” Instead, it was known as “The Passion.”

The reason: “To throw off any possible religious protesters,” according to Marion Billings, Scorsese’s longtime publicist. “The whole idea was to keep a very low profile.”

As for Scorsese’s quest: He addressed it in a chapter of the book, “Once a Catholic,” an anthology of ruminations on religion.

Scorsese wrote: “If and when I get to make it (“The Last Temptation”), finally (it) represents my attempt to use the screen as a pulpit in a way, to get the message out about practicing the basic concepts of Christianity; to love God and to love your neighbor as yourself. . . .

“Maybe, ‘The Last Temptation’ could show that Jesus fought with the human side of His nature and let people say, ‘Hey, I identify with that.’ ”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.