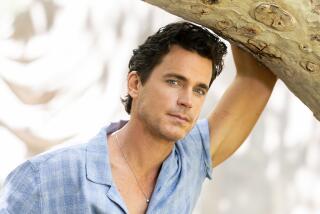

BOORMAN REMEMBERS WAR’S ‘HOPE AND GLORY’

“Some people seem to feel it’s immoral to suggest that war was fun,” said John Boorman. “But for me, a child of 7, it was. Just the right mix of exhilaration and terror. . . .”

When the British director (“Deliverance,” “Point Blank”) sat down to write his new movie, “Hope and Glory” (opening Friday), he was determined that there be no “Mrs. Miniver” touches, with everyone being impossibly brave and stiff-upper-lipped.

He would show World War II in Britain as he remembered it. For him it was a nightly fireworks display as the blitz on London gathered momentum. And he had unaccustomed freedom, as adults, concerned with momentous matters, left him to his own devices.

“I’d watched so many films of that time and they all struck me as phony,” said Boorman in Los Angeles recently. “I wanted to give a different view.

“And since the film opened in London, a lot of people have told me how gratified they were with it because they have the same memories I do.”

In this biographical reminiscence, Boorman looks back on those early days of Britain’s war with Germany and finds more laughter than tears, more exhilaration than fear.

For a lot of civilian Britons in the ,first days of the war it was like that--smiles and camaraderie, shared cups of tea and a helping hand for neighbors after the long night raids.

“People were just glad to have survived and be alive,” said Boorman. “And the rigid class system of Britain was beginning to break down as people united in a common cause and that made everyone feel good.”

Boorman was 6 when the war broke out in September, 1939, and 11 when it ended. And like a budding Garson Kanin, everything he saw he filed away for future reference.

“When she read my first draft, my eldest sister was shocked,” he said. “She realized all the things she thought she got away with as a teen-ager had been observed by me.” (His sister’s love affair with a Canadian soldier, whom she later married when she was 17, is faithfully chronicled.)

A lot had to be reconstructed for the movie. “After all,” Boorman said with a rueful laugh, “it is a period piece.”

A 650-foot-long street of 1930s suburban houses was constructed on a deserted airfield. Barrage balloons, which flew high over London throughout the war to prevent low-level bombing, had to be constructed. So did the acres of bombed buildings.

But Boorman had some luck. Gas masks from the period were found in private collections; so was a Luftwaffe flying suit, worn by a German pilot (played by Boorman’s 21-year-old son, Charley, star of his father’s “The Emerald Forest,” in a brief scene). Boorman even discovered the same patterned wallpaper that had been in his living room as a child.

And since some 30 Spitfires are still operational, he had no trouble getting hold of one for a low-flying sequence.

But the never-to-be-forgotten dogfights between Spitfires and Hurricanes of the RAF and the Luftwaffe that took place over England had only been filmed in black-and-white for newsreels. So Boorman restaged one of them in color.

“At one time it had been suggested that I make the film in black- and-white,” he said. “But I remembered all too clearly the colors of the war, the orange glow which hung over London from fires started during the blitz. I didn’t want to miss using that.”

Boorman took his mother, now 86, and his two sisters to the early rehearsals for the movie. This, he says, slightly intimidated the actors (Sarah Miles plays his mother on screen; the young Boorman is portrayed by 7-year-old newcomer Sebastian Rice Edwards).

“Most of them had never played real-life characters before,” he said, “so they were a bit nervous. But I felt that meeting my family would help enrich their roles, and I think it did.”

“Hope and Glory” was turned down by most of the major Hollywood studios. Boorman finally got his financing from distributors around the world--none from Britain, ironically, but some from its World War II adversaries, Germany, Italy and Japan.

“Finally,” he said, “David Puttnam arrived at Columbia and picked up the U.S. distribution of the film and was very supportive.”(Puttnam has since resigned as chairman of Columbia Pictures).

To date, he says, he has had the best reviews of his career both in London and New York, where the movie has already opened.

How did he think Americans would react to this highly personal view of life in London under the blitz?

“I don’t know,” he said. “I know people enjoy it when they see it--we discovered that in New York. What we’ve got to do is get them into the theaters.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.